Labour / Le Travail

Issue 83 (2019)

Article

More Dangerous Than Many a Pamphlet or Propaganda Book: The Ukrainian Canadian Left, Theatre, and Propaganda in the 1920s

On 25 November 1922, the Winnipeg branch of the Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association (ulfta) performed Yak Svit Povernuvsya Dorohy Nohamy (How the world went upside down), a play based on the Bolshevik Revolution. In the crowd, a Royal Canadian Mounted Police (rcmp) agent watched closely, committing to memory both the contents of the play and the reactions of the crowd. Afterwards, in a report to R. S. Knight, commanding officer of the Manitoba District, he conveyed his deep malaise over the night’s proceedings. The officer was concerned with the play’s final act, which displayed a post-revolutionary, Soviet society. Priests and noblemen had been demoted to drudges, ordinary citizens were giving orders, and red flag–waving children had abandoned school to sing “The Internationale” in the streets.

The officer was also troubled by the play’s overwhelmingly positive reception and requests from the crowd to repeat the show across the country. “The above show, although a comedy,” wrote the officer, “was a very revolutionary propaganda show. I consider [it] more dangerous than many a pamphlet or propaganda book, because the latter appeals to the mind, and the former to the eye. When the mind cannot agree quickly with the idea of a book,” he mused, “the eye appeals sooner.” Despite the officer’s unease, there was a silver lining: the play had been performed in Ukrainian. “If the play was performed in different languages,” he warned, “it would not be long before we would have here in Canada the establishment of the Proletarian Dictature.”1

This article examines the theatre of the Ukrainian Canadian left in the 1920s and, in particular, its use as a vehicle for both political propaganda and ethnocultural instruction. Largely focused on ulfta headquarters in Winnipeg, I show how theatre was instrumentalized to attract, entertain, and educate. By relying on rcmp reports produced by officers and informants on the ground, this article offers unique insight into the actual efficacy of the organization’s objectives. Unlike sources produced by the ulfta (newspapers, correspondence, and scripts), which are marred by the organization’s predispositions and desires to galvanize its constituents, surveillance reports serve as participatory accounts and detailed windows into the context and execution of theatrical productions. While these sources can themselves be problematic, they nevertheless offer the most comprehensive lens into the propagandistic value of the organization’s activities in the cultural sphere. In fact, without the constant surveillance of the rcmp, much of the nuance or the quotidian experiences of the theatre would remain unknown – an irony not lost on those who study the intimate relationship between the surveillance state and the left.2

For Ukrainian Canadian leftists, the 1920s represented a golden age of domestic cultural production. The strict hierarchy that constituted the communist movement in the 1930s was not yet extant and the realm of possibilities was limited only by the imagination of the organization itself. As such, the period produced a wide array of theatrical productions that were neither crass agitprop nor cheap melodrama. Rather, they were bottom-up expressions of proletarian high culture and organic reflections of the social, economic, and political realities that constituted the Ukrainian experience in Canada.

By allocating the 1920s as a unique time in the history of Canadian leftist theatre, this article intervenes in a well-established historiography that sees the origins of leftist theatre in the 1930s and, in particular, the Third Period. Whereas the 1930s are often portrayed as the high point of revolutionary theatre, the Ukrainian case points to the 1920s as a much more fruitful era for the performing arts of the left. This is not to suggest that the Ukrainian case overturns the established narrative. Instead, I submit that for ethnic radicals, who navigated the waters of the Comintern differently than Anglo-Canadians, the Third Period precipitated a return to the latent chauvinism that Lenin had warned against.3 English-language productions may have been supported, but this was to the detriment of minority language groups.4 The emphasis on the 1930s, then, is one that fundamentally ignores the monumental contributions of ethnic radicals to leftist theatre and, in turn, tacitly normalizes assumed racial and linguistic hierarchies within the movement.5

The lived experiences of the Third Period also stand in juxtaposition to Lenin’s active support of ethnic minority rights and fight against Russian chauvinism in the period of korenizatsiya (indigenization).6 While korenizatsiya has received significant scholarly attention from historians of the Soviet Union, its transnational implications and diasporic contexts have seen far less – if any – investigation.7 By offering a look into the cultural practices of the Ukrainian left in Canada, I show how this apparently internal policy had bearing beyond the Soviet orb as well as how it was activated, understood, and even refashioned in Canada. This was, in essence, korenizatsiya on the Canadian steppe.

While the topic of Canadian theatre has certainly not been neglected, the role of ethnic and/or racial communities has seen little attention in the scholarship. In the case of the ulfta, if it is not outright ignored, it is dismissed as folksy or an aside to the “proper” history of theatre.8 The subject has received far more attention from those interested in the history of Ukrainians in Canada.9 These studies, however, are largely produced from a particular ideological perspective and portray the ulfta as a villainous communist deviation and as a tool of Moscow fixated on brainwashing useful dupes.10

In many ways, this article has little to quibble with regarding the historiographical taxonomies surrounding Ukrainian leftist theatre in the Canadian context. This is because I conceptualize this research as being part of a transnational history of theatre, one that is unintelligible if limited to its national context alone.11 When seen in this light, the complex layers embedded in the performances take on greater meaning. From choices in dialect, set design, and music, the organization was participating in the larger, Soviet project of forging a national culture, as refracted through a Canadian lens. A transnational underpinning further underscores how the constituents of the ulfta formed a global consciousness from a seemingly local and parochial context. Mayhill Fowler’s conceptualization of “internal transnationalism” is particularly helpful in this regard, providing conceptual space to articulate how people could simultaneously see themselves as Ukrainian, Canadian, and Soviet.12

Canada’s surveillance apparatus had been interested in the ulfta since the organization’s inception in 1918.13 And yet, despite strong evidence that the organization was sympathetic to communism, officials were initially unsure of what exactly to make of its politics. In a note to the commissioner of the rcmp in September 1921, an officer insisted that “a great majority of [ulfta members] do not even know what communism really is” and simply want “to see the worker on the same footing as the employer.” He further noted that to describe the ulfta as communistic was nothing more than a misnomer “not used in its true sense, but simply as a nickname.” Communism, the officer assured the commissioner, “is neither being spoken, taught, or practiced by any Ukrainian in Winnipeg.”14

As the organization more closely aligned itself with the Communist Party of Canada (cpc), and the formal and informal links between the groups were entrenched, conversations regarding the ulfta shifted within surveillance circles. Styled as a radical and revolutionary outfit, the organization and its leadership now allegedly posed an existential threat to Canadian society.15 In turn, reconnaissance of the organization took on new and more intense forms. Once focused almost exclusively on high politics, and extraordinary instances of unrest, mass rallies, or militancy, the rcmp began paying attention to literally every action of the ulfta from coast to coast.

This surveillance included all of the ulfta’s cultural activities, including drama groups, choirs, and mandolin orchestras. The justification for such widespread reportage was admittedly well founded. As Rhonda Hinther shows, the cultural expressions of the ulfta were inextricably linked with political action.16 The link between culture and politics had long been on the books for the Ukrainian Canadian left. For example, the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party (usdp), which predated the ulfta, mandated that culture be an integral part of its platform.17 During the first Red Scare, which precipitated the outlawing of the usdp, the movement also emphasized its cultural policies as a way to protect itself, albeit unsuccessfully, from state repression.18 When the ulfta was established as a progeny of the usdp, there was already an institutional memory and pool of committed adherents to draw on. This meant that by the time the rcmp began its indiscriminate surveillance work on the ulfta, the cultural front of the organization was strong.

The Fifth National Convention of the ulfta, held in 1924, solidified the organization’s commitment to cultural mobilization. A Drama-Musical Commission was born, which tabled several ambitious resolutions aimed at organizing, coordinating, and growing the organization’s cultural activities.19 Among the most ambitious programs ratified by the commission was the assembly of a sophisticated pool of professional playwrights, conductors, dance instructors, and teachers. Since much of the first wave (1891–1914) of Ukrainian migrants was comprised of illiterate or semi-literate labourers, a significant portion of the talent had to be recruited from Soviet Ukraine.20 This new talent pool propelled the ulfta toward a more professional and planned approach. It also gave the organization a better grasp of the performing arts as an educational and organizational tool. Most significantly, it deepened the transnational flow of Ukrainian cultural displays, overturning the previous model of simply staging productions that were readily available, easy to learn, or quick to produce.21

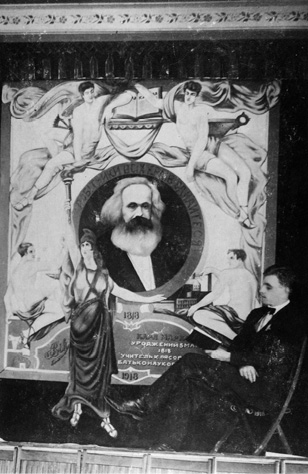

A member of the usdp on stage before the celebration of the 100th anniversary of Karl Marx’s birth in Winnipeg, 1918.

From the private collection of Larissa Stavroff.

The best-known figure to emerge from this milieu was Myroslav Irchan, a playwright, who arrived in Canada in October 1923.22 Irchan’s influence on the ulfta was considerable. Under his tutelage, a regional network of performing arts groups was established. In an average year, they performed approximately 800 plays and 550 concerts, and even travelled to the United States and the Soviet Union to hone their craft in the off season. By 1928, there were 56 drama-choral groups and 76 mandolin orchestras across the country.23

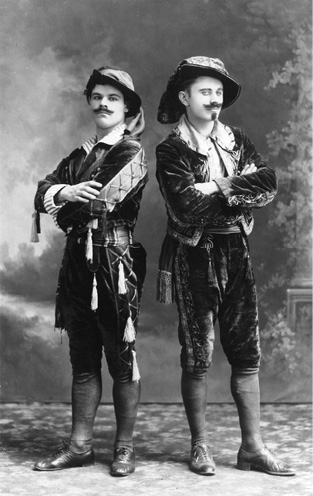

The directors of the Workers’ Theatre Studio in Winnipeg, 1920s.

From the private collection of Larissa Stavroff.

The professionalization of the performing arts facilitated a rise in popularity for the ulfta. In Winnipeg, the Workers’ Theatre Studio, a semi-professional troupe under the direct instruction of Irchan, was particularly beloved. Members of the Workers’ Theatre Studio received both practical and academic theatre training and became the principal cast for the organization’s productions. In Winnipeg, they performed to full houses every Saturday night in the fall/winter season. It was estimated that, per year, upwards of 200,000 people passed through the Winnipeg labour temple for theatrical performances alone.24 This included non-Ukrainians – mostly Jews, Russians, Poles, and the odd Anglo-Canadian – who flocked to the hall for different concerts and recitals.25

The strategic value of such high turnout was well understood by the ulfta. On a practical level, the organization was able to raise substantial funds for its various projects and causes. This included paying off all outstanding debt on the Winnipeg labour temple, investing in newspapers and schools, and providing relief for victims of floods and famines in Soviet Ukraine.26 As one rcmp officer griped, “These concerts are a continual source of revenue and make it possible for the organization to keep up a continuous propaganda campaign, in addition to providing the leaders with an easy living.”27 According to the officer, profits were so substantial that the financial standing of the organization easily surpassed all other Ukrainian Canadian groups collectively.28

Theatrical performances also allowed the organization to reach beyond a circle of committed leftists. The leadership had certainly done its research on how best to engage the larger Ukrainian Canadian community. They understood that a cultural cover offered a hook for unaligned Ukrainians that, in turn, made the politics of the organization more palatable. As such, they devoted significant energy into putting on concerts, dances, sporting events, and picnics.29 The organization was soon rewarded for these efforts. “There is not one church or organization among Ukrainians that can stop this Bolshevik movement in Canada,” an rcmp officer claimed. If the organization continued to grow at its current rate, he warned, Ukrainians would soon be cut off from state institutions and prevented from becoming “good citizens.” 30

The theatre had become the organization’s most potent form of propaganda, but the leadership was cautiously optimistic that they could mould and maintain members along ethnocultural lines alone. Much of the worry was a result of external factors that were testing the organization’s stamina. With the ulfta considered a radical outfit, its members were subject to widespread surveillance, intimidation, and harassment from government and state officials. For some, this alone was good enough reason to discourage formal membership or active participation; the stakes were simply too high. For those who continued to work openly in the movement, the risk was constant. This was especially true for those who had not yet been granted Canadian citizenship.31 When a teacher at the Ukrainian Labour Temple School in Winnipeg caught the eye of an overzealous officer reporting on a children’s concert, the teacher was immediately investigated for potential deportation.32

The ulfta was also enmeshed in a community schism. By the 1920s, the Ukrainian Canadian community was firmly divided into two distinct political camps: the pro-communist left and the anti-communist right.33 While the context for the conflict extends far beyond the theatre, it nonetheless serves as a valuable anecdote for understanding these hostilities. According to the rcmp, Ukrainian nationalists who belonged to the Canadian Ukrainian Institute Prosvita were increasingly staging theatrical productions because they realized it was an effective way of challenging the influence of the left. In fact, Prosvita began staging plays identical to those of the ulfta, often on the same nights, in an attempt to draw the crowds away from their mortal enemy. This constant battle for community recognition had a destabilizing effect on the ulfta; rcmp officers noted that its plays were not seeing their usual high turnout. While it used to be common for people to be turned away at the door, some productions were now more than half empty.34

Luckily for the ulfta, this dip in participation was only temporary and the influence of the nationalists in the cultural realm waned. Yet, behind closed doors, the leadership remained concerned that the allegiance of its members was built on a too-flimsy cultural foundation. If all that tied people to the ulfta was the theatre or the mandolin orchestra, they fretted, their support might prove fleeting. In order to ensure ongoing interest, the leadership decided to do something that the nationalists would not: they would produce cultural material that would resonate with audience members as workers and farmers as well as Ukrainians.35

With this in mind, the plays increasingly began tackling issues like workplace exploitation, unemployment, and poverty. The drama Bezrobitny (The unemployed) is emblematic of this kind of material. Set in a pre-revolutionary society, the play traces the far-reaching consequences of chronic unemployment for a small community. The rcmp report vividly sets the scene:

The stage represents a saloon of the very low type, located in a basement. Groups of unemployed are sitting by the tables, ordering drinks from time to time. At a bench in the corner are sitting a few prostitutes. At a separate table is sitting a man … called The Invisible. There is a conversation amongst one group about unemployment. One man, without one arm, argues that a worker and a dog are all the same, pointing out to his lost arm, saying that while he had both arms he was working for a starving wage, but since he lost one the boss does not want to keep him anymore. During this conversation, other workers, unemployed, are coming in. One of the prostitutes rises to meet them, asking to take her, but all the incomers refuse, showing their empty pockets. The prostitutes are weeping, and one of them says that it is the second day that her children have not had bread. The Invisible then approaches the table of the group, and buying them drinks, begins to agitate them. He says that there is no God and no devil, and that unemployment comes because the workers are stupid to work for the rich. “Look,” he says, “I am not working for the rich, but get of them what I need. You could do the same, but you need to be other men.” He tells them that they, in masses, can go and take away everything from the rich, but now is not the time for it because they have not starved long enough. He goes back to his seat and lies down on the bench.36

The theme of working-class adversity continued in Strajk (A strike), which follows a man torn between solidarity with his fellow workers and strikebreaking in order to make ends meet. While he ultimately resists scabbing, the play illustrated the choices workers and farmers had to make in order to stay afloat.37

The plays also stressed the inherently antisocial nature of capitalism. Playwrights always depicted capitalists as immoral and avaricious caricatures hell-bent on the complete subordination of the working class. Na peredodna (On the eve) follows a violent and immoral landlord who will stop at nothing to make a mint. “The corruption of the bourgeoisie is shown to such an extent,” wrote the officer who watched the play, “that it was necessary to advertise in the announcement that children under 16 years of age will not be admitted. Each pronounced sentence,” the officer continued, “[and] each action of the actors is a world of propaganda.” The officer’s final assessment that each action and word presented an entire realm of propaganda is quite astute, as the audience was quick to connect with the material. Through different lenses and vectors, they formed a theoretical understanding of their positionality under capitalism that was tied to a trans-historical and transgeographic experience of exploitation.

For the ulfta, the most tragic and intense instance of capitalist belligerence was surely World War I. Following the war’s outbreak in 1914, the Ukrainian left had mobilized its constituents against what they perceived as an imperialist conflict.38 This outlook was manifest in the plays. In Rodyna Schitkariv (The family of brushmakers), a factory worker begins to agitate against the war. He convinces his fellow workers that the capitalists encouraged war “in order to get rich on the price of the workers’ flesh.” For his protest, the factory worker is put in jail and eventually forced to the front lines where an encounter with poisonous gas takes his eyesight. In a twist, the man’s love interest is the daughter of the professor who invented the gas and made millions of dollars in profits from it. Upon learning of her lover’s fate, she rejects her father and her bourgeois upbringing, joining the revolution instead.39

F. Hordienko of the Workers’ Theatre Studio performing Rodyna Schitkariv (The family of brushmakers) in Winnipeg, 1923.

From the private collection of Larissa Stavroff.

In Batalijon Mertvyh (The battalion of the dead), Russian soldiers fighting with the Imperial Russian Army begin to question the commands of their general, whose careless advances seemed needlessly reckless. Convinced that they are being led to certain death, and increasingly disillusioned by the direction of the war, the soldiers refuse the commands. For their insubordination they are executed, but die knowing that they are doing their part to advance the revolutionary charge against the war. In the play’s epilogue, the protagonist appeals to the audience to organize: “As long as the workers will not organize, the capitalistic governments will sacrifice tens of thousands of them and their children for the benefit of capital.”40

The plays were also tasked with appealing to the ethnocultural sensibilities of the audience. Apart from simply putting bodies in seats, appeals to ethnocultural interests were meant to shape the identities of audience members. For one, all plays in this period were performed in Ukrainian. With the language not yet standardized in this period, the ulfta was helping to craft and enforce a disciplinary regime on the language itself.41 Relatedly, the costuming, dancing, and general aesthetic of the plays were part of a new, domestic creation of culture.42 The organization was forging Ukrainian traditions.43 Since there was little specific direction from the Soviets in this period, the ulfta itself was rooting for the spread of Ukrainian culture.44

The material used to appeal to Ukrainians along ethnocultural lines was always tinted red. The ulfta frequently performed Ukrainian classics rejigged to suit the specific needs of the organization. When it held a commemorative concert for Taras Shevchenko, Ukraine’s national bard, the opening speeches were quick to note that while Ukrainian nationalists might try to claim Shevchenko as their own, “he was not a nationalist, but a poet who called the slaves of Ukraine to join the slaves of other nationalities to break their chains.” The audience was reminded that in Soviet Ukraine, Shevchenko was second only to Lenin. Shevchenko as a father of the working class was constantly promoted by the organization. In a performance of Vybuhnyj Sud v Halychyni (The hurried trial in Galicia), a portrait of Shevchenko hung between Marx and Lenin on the stage.45

The celebration of Ivan Franko, another famous Ukrainian poet, similarly showed how, even when the goal was to elevate ethnic consciousness, there was always a political slant. Franko was also denied as a nationalist, a claim made easier by the fact that he had been a founding member of the socialist movement in western Ukraine. In their celebration of Franko, ulfta leadership noted that Franko “paid special attention to the Ukrainian working masses and was trying to get the workers free from capitalistic slavery.”46

Advancing ethnocultural consciousness also involved addressing the Ukrainian Question, which was concerned with Ukrainian national self-determination and freedom from imperialist – namely Polish – oppression.47 Since Polish-Ukrainian relations enjoyed a long and storied past, much theatrical material was already available. The Winnipeg branch keenly performed Taras Bulba (Taras Bulba), written by Nikolai Gogol in 1835. The play was put on multiple times to convey Ukraine’s long struggle for freedom from Polish rule. For the rcmp reporting on the play, the message was simple: “Kill your own children (or your parents) when they betray your cause.”48 Branches across the country were also treated to several performances of Shevchenko’s Haydamaky (Cossacks). The play, an adaptation of Shevchenko’s poem, sketched Polish oppression of Ukrainians in the 18th-century Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the revenge of the haydamaky bandits, who were portrayed as revolutionaries and heroes because of their struggle for freedom.49

The intent was not only to show historical examples of oppression, but also to posit solutions for the future. This, of course, meant bringing western Ukraine into the Soviet Union. Support was garnered through fictionalized dramas depicting the arrival of “red saviours” in eastern Galicia who overthrow the tormentors of Ukrainian workers and farmers and institute a Soviet government. Plays based on the actual revolution and the creation of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic were also performed, including Dvanadtsiat (The twelve), Pidzemna Halychyna (Underground Galicia), and the aforementioned Rodyna Schitkariv (The family of brushmakers). These plays tended to be performed in the month of November, when the organization commemorated those executed by Polish authorities.50

Like all good propaganda, the promotion of ethnic and class consciousness was not intended for passive consumption.51 In validating workers’ and farmers’ worst fears about capitalism, the plays and accompanying speeches promoted the notion that the time for insurrection was now.52 As such, the plays acted as manuals for revolution. Most instruction was of a distinctly practical nature. In addition to joining under the umbrella of the ulfta, Ukrainian workers and farmers were asked to formally join the cpc. If they did not join these organizations, they were told, they would never accomplish what the Soviet Republics had.53

The October Revolution served as the ultimate success story, and calls to follow the Soviet example were plentiful:

It is time for the workers and farmers of this country to take an example from the only worker and peasant Soviet Republics, and to establish here the rule of the proletariat … to assure the workers’ freedom. Can’t you see the comparison between this “free democratic” country and barbaric Bolshevik Republics? In this “God blessed, full of churches” country, thousands of workers are starving. A hundred thousand workers of this country went to war for freedom and democracy, but when they came back what conditions did they find?

The conditions they found are such as you read about in the police investigations in Montreal. Two hundred thousand unemployed, or of such employment which is not sufficient to make a living, and the poor working parents are forced to send their girls into prostitution to earn a piece of bread. And alongside with this, you see idlers living in luxury!

This is the democracy and the justice of this country, and of all capitalistic countries! This is the reason why we, workers and farmers, have to unite to educate ourselves and our children in class consciousness, and to join the cpc and the ycl [Young Communist League] which is a part of the Communist International, in order to overthrow the capitalistic rule and to establish a Soviet rule of workers and farmers.

You workers who build palaces, but are living in doghouses; you who create the wealth of this country, but live in poverty; and you farmers, who feed the idlers. Arise under the Red Banner and throw off the yoke of capitalism! Follow the example of the workers and peasants of Russia! Join the cpc, become a member of the Third International and make an end of your own and your children’s slavery. Long live the Union of Workers and Farmers! Long Live Soviet Ukraine! Long live the revolution!54

By the fifth anniversary of the Russian Revolution, branches were staging annual commemorative concerts.55 This would keep the Soviet example fresh and remind workers and farmers that a radical and emancipatory alternative was possible.

The drive for card-carrying members also extended to children.56 The logic was twofold. First, the leadership believed that children’s participation would safeguard the organization from extinction. Second, they contended that workers and farmers would soon have to “fight at the barricades in order to establish the same rule of the proletariat as they have done in Soviet Ukraine.” As such, they had to be prepared with a class-conscious army of workers and farmers – an impossible feat if the younger generation was not recruited into the fold.57

During the plays, parents were encouraged to enrol their children in the ulfta’s Youth Section as well as the ycl. They were also urged to pull their children from public schools, which were filling their minds with “patriotic dope” that made “good slaves to work … and gun meat in the time of war.”58 If parents did not enrol their children in the ulfta’s school, it was threatened, “your twelve-year-old girls [will] have to sell themselves for bread.”59

The leadership was equally interested in fortifying the press, which they saw as another important revolutionary midwife. During intermissions and in epilogues, they reminded audiences that the Canadian press was deceitful and did not reflect the opinion of the masses. Rather, the press promoted opinions that were desired only by the bourgeoisie in order to “keep the working class in ignorance” and “keep people out of the truth.”60 In order to shift hegemonic ideas in society and to further class consciousness among workers and farmers, more favourable options were needed. “Give freely [to the press],” urged the leaders, “remembering that this is your only mighty weapon to battle … until the time will come to take up other weapons and to destroy the present system of the bourgeoisie.”61 While a cynical interpretation of why the organization wanted its membership to grow is appropriate, it is simultaneously possible to take the leadership at their most sincere. The development of revolutionary infrastructure was, in fact, congruent with the dominant thinking of the First Period, which hoped and expected to export the October Revolution across the globe.

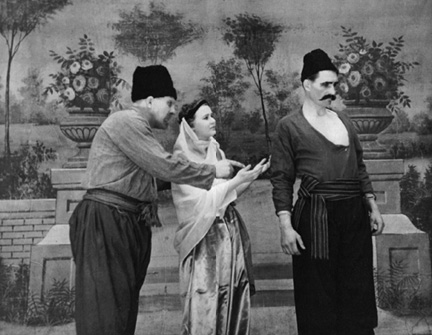

Members of the Workers’ Theatre Studio performing Hata Za Selom (The house beyond the village) in Winnipeg, 1919.

From the private collection of Larissa Stavroff.

The revolutionary manual could also be more philosophical in nature. Through plays and accompanying speeches, the audience was constantly reminded that when the time came, they had to be prepared to spill blood. As such, the plays were chock full of material relating to the total and unabashed destruction of the capitalist class.62 Death was not reserved for the bourgeoisie alone; workers and farmers had to be ready to die for the revolution, the noblest of causes. This message was reinforced in Vybuhnyj Sud v Halychyni (The hurried trial in Galicia). “Our blood will not be shed for nothing,” recited an actor portraying an eastern Galician revolutionary sentenced to death. “Over our bodies the revolution is marching [and it] will burn and destroy all parasites, capitalists, and their governments. I am ready,” he shouted as he kneeled before a firing squad: “shoot!” 63

Those who were not as eager to give their lives for the revolution were not turned away. Audiences were reminded that it was possible to be burnt out or disillusioned by the struggle. So long as they did not become class traitors, and eventually found their way back, all would be forgiven. This was driven home in Schaslyvyj Kripak (The happy serf), which follows a poet who rejects his calling to lead the revolution only to return and give his life for the cause.64 Redemption – even martyrdom – was possible, so long as one recognized the error of their ways, reaffirmed their commitment to the class struggle, and made the ultimate sacrifice.

Despite the curiously consistent emphasis on mortality, the radicals and mutineers of the future were not to mourn the dead. Instead, they were to celebrate their sacrifice, even if the revolution was betrayed. The play Yuda (Judas) follows the Spartacist uprising in Germany and ends with the arrest and murder of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. In the epilogue, the audience is told to save their tears and instead carry out the plans for which Liebknecht and Luxemburg gave their lives.65 This message was repeated over and over again. In the aforementioned Bezrobitny (The unemployed), a man begins to curse the revolution that took the lives of his comrades before being rebuked:

The Invisible says that in such a day of victory of the workers over the capitalists and their system, nobody has to weep over the victims. The revolution is worth the hundreds of victims, because there will be no more slavery and starvation for those who live and for the future generation. Afterwards [the people] ask him to tell them who he is and his name. He answers: “I am not I, I am you, your revolutionary spirit, who leads you through the years of hard work, starvation and depression, to the change of the system, and from now on the rich will work for you. Show them what it means to work and starve.”66

The words of The Invisible reminded the audience that they were embarked in a righteous campaign for working-class justice. The audience had to seize the means of production and “raise high the red banner, which is full of proletarian blood.” These calls were so well received that they frequently elicited standing ovations and wild applause.67

Audiences were also taught how to discern reactionaries, class traitors, and the bourgeoisie. The working class had to be proficient in identifying these figures to avoid falling victim to their mendacities. More importantly, they were shown how to effectively resist their duplicitous and cowardly pleas for mercy once the revolution began. Revolutionaries, the plays argued, could have no self-reproach or remorse.68 Audiences also had to be able to recognize false flags. They learned to distinguish between true class revolution, so-called worthless bourgeois or national revolution, and the feigning conciliatory efforts of the ruling elite. While the monarchy of Austria is abolished and replaced by a republic in Rodyna Schitkariv (The family of brushmakers), the audience was reminded that a republic is not an adequate substitute for revolution as it is neither led by workers and farmers nor established in their interests. Gains were only sustainable, they were told, if property was abolished and the stateless freedom of full communism was implemented.69

rcmp officers regularly confirmed the effectiveness of the plays in building revolutionary zeal. Unfortunately for the security service, officers had a hard time finding more than three or four examples of so-called ordinary plays that were not of a revolutionary nature.70 This was further complicated by the fact that even those plays deemed inoffensive began with the singing of “The Internationale” and featured rabble-rousing speeches from the ulfta leadership. Of those with explicitly radical content, the vast majority were well received. Officers recurrently suggested that each play had set a new bar for audience engagement. Perhaps nothing could top the 1923 performance of Mutyner (The mutineer). In the final scene, the protagonists overthrow their oppressors, raise their red flags, and begin singing “The Internationale.” The clapping and cheering from the crowd, which seemed to go on for ages, was so intense that the scene had to be shown twice.71

While visceral reactions were regularly chronicled, they were given special attention in the case of women and children.72 Quite predictably, whereas the passion or strong emotion of men went without much comment, or was described in normative terms, emotional reactions from women were painted quite differently. In a report from a showing of Dvanadtsiat (The twelve), the officer on file mentioned that the actors had performed with such revolutionary zeal that “many women in the audience wept, a few becoming hysterical.”73 The involvement of children garnered similar attention, as officers were very concerned about the ulfta’s work among “restless youth” who were “filled with all kinds of energy [and were] ready for violent action.”74 Far from the confines of male-dominated political life, the revolutionary theatre provided a space within the public sphere where women and children could actively participate in shaping the horizons of a radically different future.75 For the rcmp, their involvement was not only dangerous, but also deeply unnatural, as the police did not see women and children as having either the interest or capacity for political life. This commingling of age, gender, and revolutionary ideas – in a foreign language, at that – was not how politics in Canada were supposed to look.

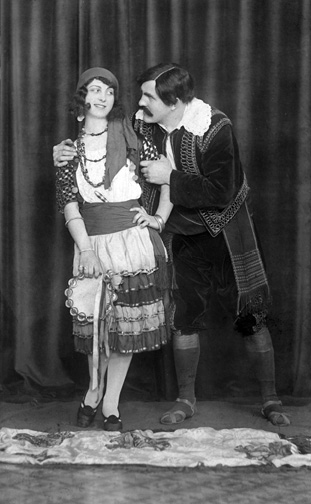

S. Yanishevska (left) and F. Hordienko (right) of the Workers’ Theatre Studio performing Aza Tsyhanka (Aza the Gypsy) in Winnipeg, 1926.

From the private collection of Larissa Stavroff.

Some officers took a very straightforward, even dismissive, approach to their reporting, dubbing these plays as “nothing but propaganda, agitation, and approval for the cause of revolution.”76 Others were somewhat cheeky in their assessments. While conceding that Chervona Armiya (The red army) was very propagandistic, the reporting officer was seemingly more concerned that “the acting was bad.”77 This officer was not alone in questioning the pool of talent in the drama groups. Writing about a performance of Schaslyvyj Kripak (The happy serf), an officer lamented that the play had not reached its full potential because of thespian mediocrity:

During the acts a very few applauded, although the play was very inspiring, and this can be explained in two ways. First: the acts were too long; there was too much philosophical talk, which is hard for common people to understand. Second: the actors were very slow. In my opinion this piece should have been played by real actors and not by amateurs. [It] would revolutionize the audience and make their blood boil to the extent of action. It is a very dangerous propaganda show and it is no wonder that it is recommended to be played by the Educational Commissariat of all the Ukrainian Theatrical Committees of Soviet Ukraine.78

Such an assessment is somewhat farcical. The officer had either developed Stockholm syndrome or spent so much time in the labour temple that he had lost all measure of perspective. And yet, the comment is revealing because it emphasizes the level of the officers’ intimacy with and expertise on their subjects.

Others took great care to underscore just how insidious the plays could be. “The play by itself is a masterpiece and of high art,” wrote an officer covering Haydamaky (Cossacks). In the officer’s assessment, the play had convinced the audience that “for principles and ideals kill even your own children.”79 The realistic nature of the plays was also covered in some detail. After a performance of Mutyner (The mutineer), an agent observed that the play had felt like “a real revolution, planned and carried out on the stage before an audience which had never seen, or even knew before, what a revolution was.”80 The showing of Zhinka v Tjurmi (The woman in the penitentiary) garnered similar reactions. The female lead “almost inspired everyone in the audience to take axes, guns, and other weapons and to begin immediately the slaughter of the bourgeoisie.”81

The threat of actualized revolution was only made more real by the enduring rumours that the ulfta was in possession of rifles. Officers divulged that they had long heard such gossip, with one officer even claiming that he had seen the guns being moved “in a very secret manner.” Before a formal investigation could occur, conspiratorial voices prevailed and the accusations against the ulfta spiralled out of control. If there were no rifles, it was reasoned, there would be “less secrecy about them.” Eventually, surveillance operations revealed that the organization did, in fact, own rifles, but they were dummies used for theatrical purposes only.82 Yet surveillance so often becomes its own justification. The ongoing whispers reinforced justifications for sustained observation of the ulfta, intensifying the gaze of government and state officials.

For some officers, the customary reportage was not enough to illuminate just how powerful the medium of theatre had become. They began dedicating increasing time to covering the plays in full. This included a breakdown of the playwright and actors, audience members and their reactions, happenings before and after the performances, detailed descriptions of the set, and a comprehensive synopsis of each act. As these reports made their way up the surveillance hierarchy, from commanding officers to the rcmp commissioner, they were further editorialized. For the agents on the ground, painting as full of a picture as possible was the only way to convey to their superiors just how influential the plays had become.

A particularly robust report was delivered to the commissioner in the case of the 1923 performance of Vybuhnyj Sud v Halychyni (The hurried trial in Galicia). The play follows the story of Ukrainians in Galicia who organize against their Polish oppressors with the help of the Red Army. The two men in charge of the revolutionary army, Sheremeta and Melnychuk, are eventually captured and sentenced to death. Their funerals consume much of the play’s final act, which was meticulously recorded by an agent:

On the stage the coffins of the two prosecuted, Sheremeta and Melnychuk, covered with red flowers. At the heads [is] a girl with the red banner in her hands, [and] on both sides [is] the choir. They sing the revolutionary funeral song, the audience rising. When finished they and all the audience remain standing. Shatulsky [an actor] gives a review of the event of the drama. “You,” he said, “who have seen how the comrades who came to free Galicia from the oppressors Were slain, by their coffins we swear not to forget the efforts of our slain comrades, and to aid not only the revolutionary movement in Galicia, but wherever such [a] movement may need our help, because our brethren are not only in Galicia, but all over where there are toilers, who are exploited by the Capitalists and their servants. Long live the revolution! Long live Soviet Ukraine! Long live the Third Internationale!” The choir finished the epilogue by singing “The Internationale” with the aid of many in the audience.

The officer noted that he had never seen the audience so inspired and agitated. On leaving the theatre that night, he overheard a woman say that the play “exposed the soul of capitalists [and] what we have to face in this country.” He also observed someone remark that they had no doubt that the actors could “carry this out in real life.” In his mind, the ulfta “could not have chosen a more propaganda and agitation play as this.” This admission troubled the seasoned officer more than usual. He complained that the whole affair had given him a headache and that he could not settle to sleep that night.83 The plays were effective indeed.

Members of the Workers’ Theatre Studio performing Yaskravi Zirky (Bright stars) in Winnipeg, 1935.

From the private collection of Larissa Stavroff.

By the end of the 1920s, the ulfta was ready to reflect on a decade of distinct achievement in the performing arts. At its Tenth National Convention, held in February 1929, a special report was delivered to celebrate the organization’s accomplishments in the cultural sphere. These achievements were certainly something to commend. Branches across the country were reporting significant increases in membership and regional networks of performing arts troupes were constantly growing.84

The announcement of the Third Period, however, ushered in an era of decline for the ulfta.85 The shift to class-on-class analysis was more than just a rhetorical shift for the organization. In the case of the theatre, it meant a complete transformation of the repertoire, wherein ethnicity was entirely separated from class. Under the new mandate, regional organizers were instructed to adjust theatrical productions to the new, correct ideological level. Serving as the shock troops of proletarian art, they were tasked with removing all “folkish potboilers” and “petty bourgeois trash” from the repertoire.

In quick succession, plays in the Ukrainian language or those dealing with the unique experiences of ethnic workers and farmers were replaced with generalized content that could appeal to all. Performers were similarly castigated. Gone were the days of creative input and flexibility; a rigid structure in which leadership ruled over drama groups with an iron first was now encouraged. Things would look different for the audience as well. They were expected to remain quiet, clap only when prompted, and refrain from standing during numbers. A re-education in the performing arts had begun.

Audiences reacted harshly to these changes, and complaints that the new plays were repetitive, boring, and less lively came pouring in. The leadership responded by doubling down and upholding the claim that the theatre of the 1920s had been overrun by a bourgeois mentality and filled with cheap vulgarity or empty traditionalism.86 Members were also reminded that speaking out against this organizational overhaul was nothing short of treason. In turn, a wave of paranoia swept the ulfta as the leadership unceasingly tried to expose the band of counter-revolutionary actors who had allegedly infiltrated the organization and planted the seeds of dissent.

The theatre was at the heart of the leadership’s strategy to weed out alleged quislings. For example, a theatrical production in April 1936 became an opportunity to expose a member accused of counter-revolutionary activity. During the play’s intermission, the man was asked to play the guitar. While he was on stage, the leadership searched his belongings for possible hints of disloyalty. After finding what they were looking for, they stormed the stage and publicly expelled him from the organization. “The Communist Party has [people] closely watching constantly,” they warned the crowd.87 This new dynamic was undoubtedly loathed and did much to dissuade future participation by all but the most committed.

Despite mounting evidence that the Third Period was taking a significant toll on the ulfta, the leadership did not budge. Forced to follow the party line, and perhaps losing sight of the threat of transitory popularity, they continued their concerted attack on the perversive activities of the 1920s. When confronted with apathetic participants and dwindling audiences, sure signs that the policy of the party was not working, the leadership blamed growing pains. The theatrical productions, they claimed, were simply adjusting so that they could finally serve their purpose as revolutionary propaganda for the movement.88

The contention that the propagandistic potential of the theatre was only realized in the 1930s clearly reflects the zeitgeist of the Third Period. Moreover, it highlights the significant limitations of a focus on the 1930s as the peak of radical theatre. By pointing to the 1920s, this article shows how the ulfta was able to create and perform grassroots and revolutionary theatrical productions that were far more effective than the material produced during the Third Period. The content of the 1920s not only catered to the organization’s distinct migrant membership, but also satisfied its internationalist political goals.

The turn toward a singular focus on class, as narrowly defined by the Comintern, only hindered the spread of class consciousness among the constituents of the ulfta. The attempt to distill the difficulties and potential contradictions that arose from the complex interplay of ethnicity and revolutionary universalism was indeed injurious to the movement. For the organization’s members, who saw themselves as Ukrainian, Canadian, and Soviet all at the same time, the particularities of their political consciousness could not be ignored when it finally came time to raise the red flag as the plays had taught them.

Many thanks to Mikhail Bjorge, Larissa Stavroff, members of the Immigration History Discussion Group in Toronto, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

1. “Report re: Ukrainian Labor Temple Association,” 27 November 1922, rcmp fonds, rg 146, vol. 95, access request ah-1999/00133 (hereafter, rcmp fonds), pt. 1, Library and Archives Canada (hereafter lac).

2. Gregory Kealey, “State Repression of Labour and the Left in Canada, 1914–20: The Impact of the First World War,” Canadian Historical Review 73, 3 (1992): 281–314; Gary Kinsman, Dieter K. Buse & Mercedes Steedman, eds., Whose National Security? Canadian State Surveillance and the Creation of Enemies (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2000); Steve Hewitt, Riding to the Rescue: The Transformation of the rcmp in Alberta and Saskatchewan, 1914–1939 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006); Daniel Francis, Seeing Reds: The Red Scare of 1918–1919, Canada’s First War on Terror (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2010); Reg Whitaker, Gregory S. Kealey & Andrew Parnaby, Secret Service: Political Policing in Canada from the Fenians to Fortress Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012); Greg Kealey’s eight-volume rcmp Security Bulletins series. For a specific examination of the surveillance done on Ukrainian Canadians, see Myron Momryk, “The Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Surveillance of the Ukrainian Community in Canada,” Journal of Ukrainian Studies 28, 2 (Winter 2003): 89–112.

3. Vladimir Lenin, “On Soviet Rule in the Ukraine,” November 1919.

4. Robin Endres, introduction to Richard Wright & Robin Endres, eds., Eight Men Speak and Other Plays from the Canadian Workers’ Theatre (Toronto: New Hogtown Press, 1976); Toby Gordon Ryan, Stage Left: Canadian Theatre in the Thirties (Toronto: CTR, 1981); Alan Filewod, “A Qualified Workers Theatre Art: Waiting for Lefty and the (Re)Formation of Popular Front Theatres,” Essays in Theatre 17, 2 (May 1999): 111–128; Alan Filewod, “Performance and Memory in the Party: Dismembering the Workers’ Theatre Movement,” Essays on Canadian Writing 80 (Fall 2003): 59–77; Candida Rifkind, Comrades and Critics: Women, Literature, and the Left in 1930s Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009). A notable exception to the Depression-era arguments is James Doyle, Progressive Heritage: The Evolution of a Politically Radical Literary Tradition in Canada (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2002).

5. The Atlantic and Soviet examples of the tendency to focus on the 1930s are equally stark. Harold Clurman, Famous American Plays of the 1930s (New York: Dell, 1959); Morgan Himmelstein, Drama Was a Weapon: The Left-Wing Theatre in New York, 1929–1941 (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1963); Harold Clurman, The Fervent Years: The Story of the Group Theatre and the Thirties (New York: Hill & Wang, 1966); Jay Williams, Stage Left (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974); Malcolm Goldstein, The Political Stage: American Drama and Theatre of the Great Depression (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974); Raphael Samuel, Ewan MacColl & Stuart Cosgrove, Theatres of the Left, 1880–1935: Workers’ Theatre Movements in Britain and America (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985); Wendy Smith, Real Life Drama: The Group Theatre and America, 1931–1940 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990); Robert Shulman. The Power of Political Art: The 1930s Literary Left Reconsidered (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000); Matthew Worely, “For a Proletarian Culture: Communist Party Culture in Britain in the Third Period, 1928–35,” Socialist History 18 (2000): 70–91.

6. Lenin, “The Ukraine,” June 1917; Lenin, “Letter to the Workers and Peasants of the Ukraine – Apropos of the Victories over Denikin,” January 1920. For more on this period, see Yuri Slezkine, “The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism,” Slavic Review 53, 2 (Summer 1994): 414–452.

7. By this I mean that there are no explicit studies of how korenizatsiya was understood in diasporic communities. In a roundabout way, however, all historians interested in the negotiation of eastern European diasporic identity deal with questions of how communities rejected, embraced, or altogether ignored the state-sanctioned ethnic identities crafted by the Soviet Union and/or its competitors.

8. The exception is the excellent work of Alan Filewod. Yet even here the theatre of the Ukrainian left receives scant attention and is portrayed, somewhat fairly, as apart from the historical, intellectual, and theoretical landscape of Canada’s theatre history. The Jews and Finns, also active participants in Canada’s ethnic left, similarly lack significant attention in this historiography. The sole investigation into Finnish leftist theatre is Taru Sundstén, “The Theatre of the Finnish-Canadian Labour Movement and its Dramatic Literature, 1900–1939,” in Michael G. Karni, ed., Finnish Diaspora: Canada, South America, Africa, Australia and Sweden (Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1981), 77–91. For more on leftist Jews and the theatre, see Ester Reiter, A Future without Hate or Need: The Promise of the Jewish Left in Canada (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2016).

9. The most comprehensive study to date is Jars Balan, “Backdrop to an Era: The Ukrainian Canadian Stage in the Interwar Years,” Journal of Ukrainian Studies 16, 1 (1991): 89–113. This piece is useful for contextualizing the period, but it sees the theatre movement as particularly Canadian as opposed to something enmeshed within an international or revolutionary context. See also Jars Balan, “A Losing Cause: Refighting the Revolution on the Ukrainian Canadian Stage,” in Andrew Donskov & Richard Sokolski, eds., Slavic Drama: The Question of Innovation (Ottawa: University of Ottawa, 1991), 226–234; Suzanne Hunchuck, “A House like No Other: An Architectural and Social History of the Ukrainian Labour Temple, 523 Arlington Avenue, Ottawa, 1923–1967,” PhD thesis, Carleton University, 2001. The special edition of the Journal of Ukrainian Studies titled “Ukrainians in Canada between the Great War and the Cold War” (28, 2 [Winter 2003]) is contextually useful, but not immediately applicable to this study.

10. Ukrainian Canadian theatre is explored in cursory detail in Alexandra Pritz, “Ukrainian Cultural Traditions in Canada: Theatre, Choral Music and Dance, 1891–1967,” master’s thesis, University of Ottawa, 1977. The text, however, leaves the vast majority of the ulfta’s undertakings either ignored or significantly diluted. The Ukrainian left similarly sees little attention in Alexandra Pawlowsky, “Ukrainian Canadian Literature in Winnipeg: A Socio-Historical Perspective, 1908–1991,” PhD thesis, University of Manitoba, 1997. For an introduction to the manifold issues in Ukrainian historiography, see Georgiy Kasianov, “‘Nationalized’ History: Past Continuous, Present Perfect, Future…,” in Georgiy Kasianov & Philipp Ther, eds., A Laboratory of Transnational History: Ukraine and Recent Ukrainian Historiography (Budapest and New York: Central European University Press, 2009), 7–24; Mark von Hagen, “Revisiting the Histories of Ukraine,” in Kasianov & Ther, eds., Laboratory of Transnational History, 25–50; Serhy Yekelchyk, “A Long Goodbye: The Legacy of Soviet Marxism in Post-Communist Ukrainian Historiography,” Ab Imperio 2012, 4 (2012): 401–416.

11. For more on the transnational history of theatre, see Christopher Balme & Berenika Szymanski-Düll, eds., Theatre, Globalization and the Cold War (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

12. Mayhill Fowler, “Mikhail Bulgakov, Mykola Kulish, and Soviet Theater: How International Transnationalism Remade Center and Periphery,” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 16, 2 (2015), 263–290. See also Fowler, Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge: State and Stage in Soviet Ukraine (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017).

13. For more on the creation of the ulfta, see Peter Krawchuk, Our History: The Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Movement in Canada, 1907–1991 (Toronto: Lugus, 1996).

14. “Report re: Communist Party, Ottawa, Ontario,” 11 September 1921, rcmp fonds, pt.1, lac.

15. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 23 January 1923, rcmp fonds, pt.1, lac.

16. Rhonda Hinther, Perogies and Politics: Canada’s Ukrainian Left, 1891–1991 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017), 5.

17. Peter Krawchuk, Our History, 331–332.

18. On 25 September 1918, the government of Prime Minister Robert Borden passed an order-in-council (PC 2384) that banned the usdp as well as thirteen other groups. The full text can be found in John Herd Thompson & Frances Swyripa, eds., Loyalties in Conflict: Ukrainians in Canada during the Great War (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 1983), 193–196.

19. Peter Krawchuk, Our Stage: The Amateur Performing Arts of the Ukrainian Settlers in Canada (Toronto: Kobzar, 1981), 43.

20. Paul Magocsi, A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 324.

21. Krawchuk, Our Stage, 90; Peter Krawchuk, The Unforgettable Myroslav Irchan: Pages from a Valiant Life (Edmonton: Kobzar, 1998), 7–10; “Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Assn.,” 28 May 1928, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

22. Krawchuk, Unforgettable Myroslav Irchan, 10. The story of Irchan has a tragic ending. Shortly after returning to Soviet Ukraine in June 1929, he was arrested as an alleged counter-revolutionary and exiled to Siberia, where he was executed. The fate of Irchan triggered a significant deviation from the ulfta known as the Lobay movement. See John Kolasky, Prophets and Proletarians: Documents on the History of the Rise and Decline of Ukrainian Communism in Canada (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 1990); Andrij Makuch, “Fighting for the Soul of the Ukrainian Progressive Movement in Canada: The Lobayites and the Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association,” in Rhonda Hinther & Jim Mochoruk, eds., Reimagining Ukrainian Canadians: History, Politics, and Identity (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 376–400.

23. Krawchuk, Our Stage, 92–94. For more on the remarkable achievements of Irchan in Canada, see Krawchuk, Unforgettable Myroslav Irchan, as well as the unpublished manuscript by Robert Klymasz & Jars Balan, Myroslav Irchan: A Chronology of His Life and Legacy.

24. Hinther, Perogies and Politics, 37; Krawchuk, Unforgettable Myroslav Irchan, 17; Krawchuk, Our Stage, 43, 57.

25. “Report re: Ukrainian Labor Temple Association – Winnipeg, Man.,” 16 October 1922, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Assn.,” 24 January 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association – Winnipeg,” 27 February 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association – Winnipeg,” 20 March 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association – Winnipeg,” 19 October 1926, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association – Winnipeg,” 14 December 1926, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

26. Krawchuk, Our Stage, 32, 100.

27. Krawchuk, Our Stage, 32, 100.

28. “Re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association,” 15 September 1926, rcmp fonds, pt.2, lac.

29. “Report re: Ukrainian Labor-Temple Ass’n.,” 14 February 1933, rcmp fonds, pt. 3, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association – Winnipeg – Dance Performance at the U.L.F.T.A.,” 28 April 1927, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Assn. – Winnipeg,” 14 June 1926, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac. Rhonda Hinther argues that cultural outlets also offered a space for (mostly) men to exert power and agency in a way that might not have been possible in their working lives. Hinther, Perogies and Politics, 35.

30. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association, Winnipeg,” 4 June 1926, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac. This strategy served the ulfta well in the long term. The organization’s parallel focus on culture and politics created a wholesale community for its members, who, in turn, could live their lives almost entirely in the context of their own ethnic, radical community. This cultivated significant loyalty that would be difficult to break. For more on community building, see Jim Mochoruk, “‘Pop & Co’ versus Buck and the ‘Lenin School Boys’: Ukrainian Canadians and the Communist Party of Canada, 1921–1931,” in Hinther & Mochoruk, eds., Reimagining Ukrainian Canadians, 331–375.

31. In fact, even naturalized citizenship was not a guarantee against deportation. See Barbara Roberts, From Whence They Came: Deportation from Canada, 1900–1935 (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1988), 129.

32. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Assn., Winnipeg,” 27 May 1925, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

33. For more on this split, see John Kolasky, The Shattered Illusion: The History of Ukrainian Pro-Communist Organizations in Canada (Toronto: PMA Books, 1979); Kolasky, Prophets and Proletarians; Lubomyr Luciuk & Stella Hryniuk, eds., Canada’s Ukrainians: Negotiating an Identity (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991); Krawchuk, Our History; Lubomyr Luciuk, Searching for Place: Ukrainian Displaced Persons, Canada, and the Migration of Memory (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000).

34. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association – Winnipeg,” 5 February 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association – Winnipeg,” 22 January 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

35. Hinther, Perogies and Politics, 35.

36. “Review of the Show Bezrobitny (The Unemployed),” Winnipeg, 6 November 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac.

37. “Re: Dramatic Performance given at the Ukrainian Labour Temple, April 28, 1923,” Winnipeg, 30 April 1923, rcmp fonds, pt.1, lac.

38. Krawchuk, Our History, 19. “The war brings nothing good to the poor,” stated an editorial in the newspaper Robochyi narod (The working people), “only losses, and ever more victims. From a moral point of view, war is a crime of present-day society … [and] for workers the war is of no use at all.”

39. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association,” 2 February 1925, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac. In many ways, these plays were simple modifications of Ukrainian melodramas for revolutionary ends. In a study of pre-revolutionary plays, Orest Martynowych notes that the theatrical works available in the standard Ukrainian Canadian catalogue numbered only perhaps 200. The classics were of little artistic value and generally focused on “the tragic gate of women who were beaten, abandoned, murdered or driven to suicide by unfaith husbands, the local landowner, or older bachelors.” Martynowych, Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891–1924 (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 1991), 292. It was this set of 19th-century classics that were unfairly lampooned and disparaged by Peter Hunter in 1934 when he wrote, “The Ukrainians stressed folk dancing, mandolin orchestras, and plays which always seemed to revolve around a buxom peasant girl whose poor parents and her chastity were threatened by the local landowner.” Hunter, Which Side Are You On, Boys? Canadian Life on the Left (Toronto: Lugus, 1988), 19.

40. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Assn.,” 22 November 1927, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

41. Like the Soviets, the Ukrainians were attempting to diachronically construct an ethnocultural base that would serve as the foundation for cementing what Ukrainian-ness, as they understood it, actually was. By law under Tsarist rule, only folksy pastoral pieces made it past the censor. Now, Ukrainians could construct a representative canon, one that educated people and expressed honest social critiques. James Dingley, “Ukrainian and Belorussian: A Testing Ground,” in Michael Kirkwood, ed., Language Planning in the Soviet Union (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1990), 174–188; D. M. Corbett, “The Rehabilitation of Mykola Skrypnyk,” Slavic Review 22, 2 (1963): 304–313; Matthew Pauly, Breaking the Tongue: Language, Education and Power in Soviet Ukraine, 1923–1931 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014).

42. As Lars Kleberg notes, the early revolutionary period was grandiose and ambitious. The Soviets were “inhibited on the one hand by the economic crisis and the initially almost total boycott of the cultural intelligentsia, and on the other hand by the absence within the party and government of a coherent theory that would serve to guide cultural policy.” Kleberg, Theatre as Action: Soviet Russian Avant-Garde Aesthetics (London: Macmillan, 1993), 9.

43. Fowler, Beau Monde on Empire’s Edge, 119.

44. ulfta theatre, which was a mix of dramatic performance, crowd participation, and political speeches, closely mirrored that of the early revolutionary period, when political plays were in short supply and limited circumstances demanded austerity on production elements. Murray Frame, “Theatre and Revolution in 1917: The Case of the Petrograd State Theatres,” Revolutionary Russia 12, 1 (1999): 91.

45. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association,” 19 March 1925, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 7 May 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac.

46. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association, Winnipeg,” 1 June 1926, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

47. For more on Polish Canadian communists, see Patryk Polec, Hurrah Revolutionaries and Polish Patriots: The Polish Communist Movement in Canada, 1918–1950 (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015).

48. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Assn,” 1 June 1927, rcmp fonds, pt.2, lac.

49. “Report re: Performance given at the U.L.T.,” 24 November 1926, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

50. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 7 May 1923, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 19 November 1924, rcmp fonds, pt.2, lac. In conjunction with these plays, the organization staged anniversary concerts commemorating the revolutionary leaders. In 1923, these concerts raised over $15,000 for the ulfta.

51. As Matthew Popovich, a ulfta leader, noted, “All comrades who are labouring in [drama and music] are doing it in order to aid materially the organization and not only for educational purposes.” “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association Concert Meeting at the U.L.T. Oct. 12th,” 14 October 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

52. As such, all plays emphasized the unjust disposition of society and the chronic exploitation of workers and farmers. This was accentuated by speeches delivered at the performances, where themes of equity and abuse dominated. “I wonder,” pondered Matthew Shatulsky, a leader in the movement, “who benefits by whom? Put the capitalist out on a secluded island with all his heaps of gold, without the workers’ toil he will die like a fly in winter.” Hinther, Perogies and Politics, 40.

53. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association,” 24 January 1928, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Assn., Winnipeg,” 27 May 1925, lac.

54. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association,” 27 January 1925, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

55. “Report re: Ukrainian Labor Temple Association – Winnipeg, Man.,” 31 October 1922, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac.

56. For more on the history of children and radicalism in a North American context, see Paul Mishler, Raising Reds: The Young Pioneers, Radical Summer Camps, and Communist Political Culture in the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999); Reiter, A Future without Hate or Need; Hinther, Perogies and Politics, 75–102.

57. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Assn.,” 27 March 1928, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Assn., Winnipeg,” 12 September 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac.

58. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 21 December 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Assn., Winnipeg,” 31 January 1928, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

59. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 27 January 1925, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

60. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 25 March 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association – Concert Meeting,” 3 November 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

61. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association – Concert Meeting,” 19 November 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association – Concert Meeting,” 25 March 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

62. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association, Winnipeg,” 23 January 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac.

63. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 7 May 1923, lac.

64. “Report re: Ukrainian Labor Temple Association – Winnipeg, Man.,” 16 October 1922, lac.

65. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association,” 24 January 1928, lac.

66. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 6 November 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac.

67. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association – Winnipeg,” 3 March 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

68. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 28 May 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac.

69. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association,” 2 February 1925, lac.

70. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association – Winnipeg,” 3 March 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac; “Ukrainian Labour Temple Association Dramatic Performance,” 22 October 1924, rcmp, rg 146 vol. 95, access request AH-1999/00133, pt. 2, lac; “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Temple Association – Play and Concert at the U.L.T.,” 27 October 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

71. “Ukrainian Labour Temple Association, Winnipeg,” 23 January 1923, lac.

72. For more on gender, childhood and the Ukrainian left see Frances Swyripa, Wedded to the Cause: Ukrainian-Canadian Women and Ethnic Identity, 1891–1991 (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1991); Stacey Zembrzycki, “There Were Always Men In Our House: Gender and the Childhood Memories of Working-Class Ukrainians in Depression-Era Canada,” Labour/Le Travail 60 (Fall 2007): 77–105; Rhonda Hinther, “Generation Gap: Canada’s Postwar Ukrainian Left,” in Hinther & Mochoruk, eds., Reimagining Ukrainian Canadians, 23–53; Hinther, Perogies and Politics, 75–102.

73. “Ukrainian Labour Temple Association,” 13 February 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

74. “Report re: Ukrainian Labor-Temple Ass’n.,” 14 February 1933, lac.

75. This is not to suggest that the experiences of women and children were not still tinted by the misogyny, systematic discrimination, and general aloofness that characterized many ethnic and/or radical organizations in this period. The Ukrainian Canadian case is explored in Swyripa, Wedded to the Cause, Chapter 4; Joan Sangster, “Robitnytsia, Ukrainian Communists, and the ‘Porcupinism’ Debate: Reassessing Ethnicity, Gender, and Class in Early Canadian Communism, 1922–1930,” Labour/Le Travail 56 (Fall 2005), 51–89; Stacey Zembrzycki, “I’ll Fix You! Domestic Violence and Murder in a Ukrainian Working-Class Immigrant Community in Northern Ontario,” in Hinther & Mochoruk, eds., Reimagining Ukrainian Canadians, 436–464; Hinther, Perogies and Politics, 50–74.

76. “Review of the Show Bezrobitny (The Unemployed),” 6 November 1923, lac.

77. “Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association,” 7 March 1932, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

78. “Report re: Ukrainian Labor Temple Association – Winnipeg, Man.,” 16 October 1922, lac.

79. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour Farmer Temple Association – Winnipeg,” 24 November 1926, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

80. “Re: The Mutineer or The Son of Revolution,” 23 January 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac.

81. “Play and Concert at the U.L.T.,” 27 October 1924, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

82. “Report re: Firearms Alleged to Be in Communist Hands,” 13 April 1932, rcmp fonds, pt. 2, lac.

83. “Re: The Twelve Played at the Ukrainian Labour Temple,” 28 May 1923, rcmp fonds, pt. 1, lac.

84. Krawchuk, Our Stage, 89–91.

85. For more on the Third Period, see Duncan Hallas, The Comintern: A History of the Third International (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016), chap. 6.

86. Krawchuk, Our Stage, 100–104.

87. “Report re: Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Ass’n., Winnipeg,” 23 April 1936, rcmp fonds, pt. 3, lac.

88. Krawchuk, Our Stage, 102–104.

Kassandra Luciuk, “More Dangerous Than Many a Pamphlet or Propaganda Book: The Ukrainian Canadian Left, Theatre, and Propaganda in the 1920s,” Labour/Le Travail 83 (Spring 2019): 77–103, https://doi.org/10.1353/llt.2019.0003.

Copyright © 2019 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2019.