Labour / Le Travail

Issue 92 (2023)

Research Note / Note de recherche

A Crusading Voice for the Mining West: How the Rossland Evening World Served Militant Workers at the Turn of the 20th Century

Abstract: The Rossland Evening World, a four-page daily dedicated to the mineworkers of British Columbia’s bustling West Kootenay mining town of Rossland, first appeared on May Day 1901 – just in time to do battle with local mine owners in the historic 1900–01 miners’ strike. The World may have owed its existence in part to William “Big Bill” Haywood, a founder of the militant Western Federation of Miners (wfm) and the Industrial Workers of the World. On visiting the town and the prospectors’ camp in the 1890s, Haywood saw that Rossland would soon grow into a thriving Pacific Northwest mountain community with a steady increase in wfm membership. He encouraged the miners to form wfm Local 38, possibly the first wfm local in Canada, and soon a dozen Kootenay locals formed wfm District Association 6. A wfm grant followed to help launch the local and the new daily. Amid growing frustration with bad working conditions and mine owners’ refusal to recognize the wfm, the World became a welcome sister to the wfm’s Miners’ Magazine, dedicating itself to “the Interests of Organized Labor.” By the fall of 1900, the strike of 1,400 miners was on, and the World published news and analysis throughout the region. Ultimately the strike was lost, but the World carried on until 1904. As its legacy, it showed how a daily newspaper could help build community support and provide a defence for the local unionized workforce.

Keywords: Rossland, Kootenay, mining, labour journalism, 1901 strike, shorter hours, Wobblies, Big Bill Haywood, Western Federation of Miners

Résumé : Le Rossland Evening World, un quotidien de quatre pages dédié aux mineurs de la ville minière animée de West Kootenay, en Colombie-Britannique, est apparu pour la première fois le 1er mai 1901 – juste à temps pour se battre avec les propriétaires de mines locaux dans la grève historique des mineurs de 1900–01. Le World doit peut-être son existence en partie à William «Big Bill» Haywood, un fondateur de la militante Western Federation of Miners (wfm) et de l’Industrial Workers of the World. En visitant la ville et le camp des prospecteurs dans les années 1890, Haywood a vu que Rossland deviendrait bientôt une communauté de montagne prospère du nord-ouest du Pacifique avec une augmentation constante du nombre de membres de wfm. Il a encouragé les mineurs à former la section locale 38 de wfm, peut-être la première section locale de wfm au Canada, et bientôt une douzaine de sections locales de Kootenay ont formé l’association de district 6 de wfm. Une subvention de wfm a suivi pour aider à lancer la section locale et le nouveau quotidien. Au milieu de la frustration croissante face aux mauvaises conditions de travail et au refus des propriétaires de mines de reconnaître le wfm, le World est devenu publication sœur bienvenue du Miners’ Magazine du wfm, se consacrant aux « intérêts du travail organisé ». À l’automne 1900, la grève de 1 400 mineurs était en cours et le World publiait des nouvelles et des analyses dans toute la région. En fin de compte, la grève a été perdue, mais le World a continué jusqu’en 1904. En tant qu’héritage, il a montré comment un quotidien pouvait aider à renforcer le soutien de la communauté et à défendre la main-d’œuvre locale syndiquée.

Mots clefs : Rossland, Kootenay, industrie minière, journalisme syndical, grève de 1901, réduction du temps de travail, Wobblies, Big Bill Haywood, Western Federation of Miners

“No political movement can be healthy unless it has its own press.”

– James Weinstein, founder, In These Times

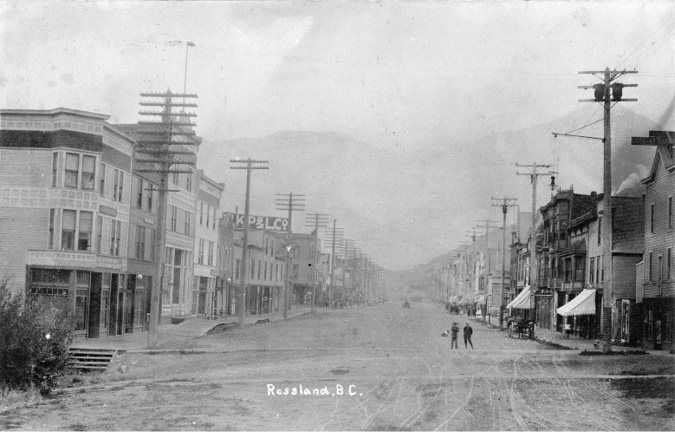

The Rossland Evening World first appeared on May Day 1901 as a four-page daily dedicated to the mineworkers of British Columbia’s bustling West Kootenay mining town of Rossland. The pop-up prospectors’ camp that a local historian of the day envisaged as “the nucleus of a big city” had blossomed into a thriving mountain community since its incorporation in 1897 and was, by that time, arguably the fourth-largest city in British Columbia.1 The Sandon Paystreak, a pioneer weekly serving the nearby ore-rich Slocan Valley, enthusiastically crowned the World “the first labor daily to make its appearance in Canada.”2 This was an overstatement, but with the arrival of the World, the Kootenay labour movement could claim to have given birth to the first labour daily in western Canada.3

In a region where hardrock miners had embraced the militant Western Federation of Miners (wfm), and with rumours of a strike in the mines circulating that spring, Rossland was a likely place for the founding of a new daily labour paper. Home to “legions of boomers, tinhorns, prospectors, women of easy virtue … drifters, gamblers, [and] petty criminals,” Rossland had already supported two daily newspapers that served a population of 6,000 miners and their families.4 A third daily was launched but collapsed in December 1900. Clearly, Rossland had many news readers, and given the strength of support for the wfm in the city, a labour paper could have well-founded hopes to find a large audience.

Columbia Avenue, Rossland, c. 1900.

Courtesy of the Columbia Basin Institute of Regional History.

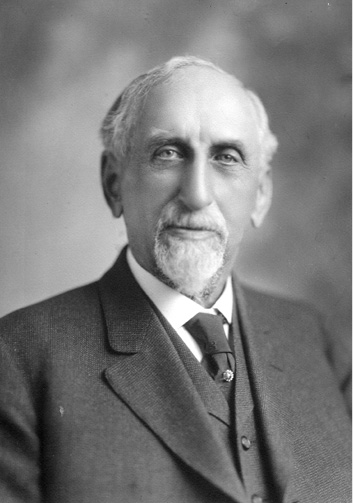

Socialist thinking was taking root in the mining communities of British Columbia in the late 1890s. By 1900, copies of Citizen and Country, a Toronto socialist publication soon to move to BC, were finding an “eager audience among miners in British Columbia and Alberta and among low-status eastern European workers.”5 Rossland hosted visits from luminaries such as the wfm’s William “Big Bill” Haywood, a founder of the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies), and possibly its famous troubadour Joe Hill.

Haywood encouraged the Rossland workers to form wfm Local 38, possibly the first wfm local in Canada, and soon a dozen Kootenay locals formed wfm District Association 6. Many of the new wfm members hailed from border states such as Washington, Idaho, and Montana where working-class roots were strong among immigrant labourers, as were socialist beliefs. As historian Robert Babcock notes, “American miners as well as American money swept into the Canadian mining camps bringing trade union ideas with them.”6 The union, with help from its international organ, the Miners’ Magazine, proceeded to organize other locals throughout the Kootenay region and support local strikes. Sensing the growing frustration with bad working conditions and mine owners’ refusal to recognize the wfm, the World soon became a welcome sister publication to the magazine.7

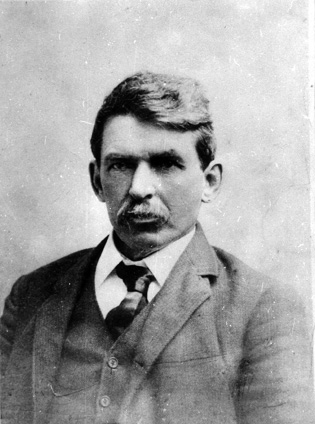

William “Big Bill” Haywood.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-H261-6755.

Two historians of the early labour movement in Rossland – Jeremy Mouat and A. Ross McCormack – refer to the paper sparingly if at all. But a close reading of the World over the course of its three-year run provides a new vantage on class struggle in Rossland at the turn of the 20th century. The daily is a key source for recovering workers’ views on events, principles and values at a moment that saw labour confront several powerful internationalist capitalists. Contextualizing this source requires an understanding of the material circumstances of the paper itself. How did the World operate, and what were the reasons for its ultimate demise? This article explores these themes and questions in retracing the World’s coverage of one of the most dramatic struggles in the history of Canada’s mining West, the 1900–01 Rossland miners’ strike.

Weekly Supports Miners, Advocates Higher Wages

The Industrial World, predecessor to the daily World, was “devoted to the Interests of Organized Labor” as the “Official Organ of District Union, No. 6, W.F.M.”8 Funded by the wfm locals, it first published on 17 September 1899. Setting the tone for the future daily in its second edition, the Industrial World declared that its “efforts will be to build up and not to tear down. It will support to the extent of its influence the establishment of all industries in which the workingman has the least concern. It will be fearless in the expression of opinions well found in fact and slow to offend others who differ with its views.” The editorial added, “the World believes that in advocating high wages it not only aids the working man to better his condition, but makes it possible for the merchant to prosper as well.”9 It juxtaposed itself against the local press aligned with capital. The editor, De Lafayette Flynt, decried the mainstream dailies for not mentioning the arrival of the new weekly. “The Miner and the Record cannot be expected to recognize the working people,” he wrote. “They are not with them and are not bashful about indicating that fact.”10

The Rossland Miner had already earned a reputation for its on-again, off-again support for the mineworkers. Robert Scott was elected mayor in 1897 with editorial support from the Rossland Record, the city’s oldest newspaper.11 When the election dust settled, Scott rewarded the Record and its mercurial founder, Eber C. Smith, with an exclusive contract to fulfill all the city’s printing requirements. In October, however, Smith became embroiled in a dispute with International Typographical Union Local 335, which declared the Record an “unfair shop” and revoked its status as a union shop. Such a label was a potential kiss of death in a union town where a bylaw required the city’s printing needs go to a union shop. The dispute resulted in the Record losing the contract, which then went to the Miner.

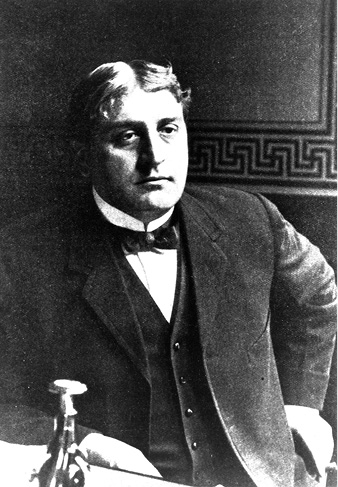

Daniel C. Corbin, railway and mining mogul.

Courtesy of the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture/Eastern Washington State Historical Society, Joel E. Farris Research Library and Archives (Wm Roberts Collection), L93-18.128.

Mining and railway magnate Daniel C. Corbin bankrolled and controlled the Miner, and it soon began to promote Corbin’s railway route to the United States. His strategy was to ship ore south from his Canadian mines, thereby bypassing the Trail smelter, which F. Augustus Heinze, the young copper king from Butte, Montana, had built and begun operating in early 1896. But in 1897, Heinze secretly bought the Miner from Corbin, with Toronto Globe correspondent Frederick Colvert Moffatt fronting for Heinze as nominal publisher.

Not surprisingly, the paper’s editorial stance changed radically. In September 1897, Heinze began using the paper to promote the shipment of local ores to his Trail smelter, back an export tax on raw ore, and attack the Canadian Pacific Railway (cpr) for not building a rail line into the district earlier. In 1899, Heinze’s interests in shaping the editorial line of the Miner disappeared with the sale of the smelter to the cpr, in a deal worth $800,000, but he kept the paper. In April 1900, Moffatt was replaced, but Rossland newspaper readers would hear from him again soon.

In May 1901, on the eve of the World’s launch as a daily, Heinze sold the Miner to the Le Roi Mining Company. Charles A. Gregg, former editor of the Victoria Globe, became president and managing editor. Initially, the World cheered Gregg’s appointment, praising his intention to be “fearless in the denunciation of anything calculated to work injury to the camp.”12 Its view of Gregg quickly changed, however; the following day, it chastised him for denouncing the miners’ union. It was the beginning of a long string of negative comments in a war of editorials.

F. A. Heinze, Trail smelter founder.

Courtesy of the Trail Historical Society.

The new owner of the Le Roi – the British America Corporation (bac) in London, England – was as determined as Corbin and Heinze to promote its financial interests in local mines. It was also prepared, as McCormack writes, to engage in the tactics that characterize the “often brutal capitalism of the American West” and take up the challenge of the wfm’s “proletarian crusade” through “a series of pitched battles with great corporations.”13 What the financiers had not counted on was a labour movement prepared to do battle with them – with its own, new daily paper dedicated to opposing them.

Labour Unrest Persists in the Slocan Silver Mines

Labour unrest had been percolating in Rossland since at least 1899. When a strike for higher wages and compliance with the eight-hour workday law broke out in June at the Slocan mines, including the silver mines at Sandon, the weekly World supported the wfm workers. The weekly published the workers’ united union platform and lashed out at the Record, which, “thinking to strike a telling blow at unionism, … harped on the same chords of the eight-hour law, labor trouble, the bad outlook for business, etc.”14 The Slocan miners won a $3.25 daily wage rate, up from $3, and an eight-hour day. The victory also led to a rush to join the wfm in Kootenay mining communities and, consequently, some badly needed subscriptions to the World.

On May Day 1901, the weekly changed its name to the Rossland Evening World and began publishing daily in direct competition with the Rossland Miner, which had become the unabashed voice of the mine owners. The daily World had declared itself an “advocate [of] the cause of organized labor.”15 Operated by the World Publishing Company, the new daily officially represented wfm Local 38 and wfm District Association 6.16

Local 38, chartered in 1895, represented one of the wfm’s early footholds in Canada, and by 1901, it had grown in influence across the district. The union built the Rossland Miners’ Union Hall in 1898, and its newspaper was soon functioning as the voice of organized labour in the whole district. As historian Gerald Boucher notes, “despite the attractions of the saloon, by 1900 there was one working-class institution of undeniably greater importance to the Kootenay hardrock miner – the union.”17 The daily paper was an important means of facilitating the connection between the miners and their union.

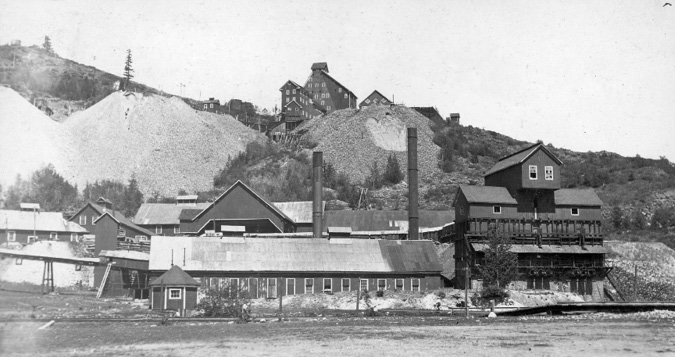

The Le Roi mine in Rossland.

Courtesy of the Trail Historical Society.

International Typographical Union Local 335’s union label appeared in the World masthead, but no editor was named, leading to much speculation about who was penning the well-crafted and often pointedly critical editorials.18 On 13 May, James H. Fletcher’s name appeared in the World masthead as “manager,” but still no editor was identified. In the summer of 1900, Fletcher worked at the Record, where he undoubtedly took part in the union-led boycott of the paper that ultimately led to its demise later that year. On 23 August 1900, he was elected secretary-treasurer of the Rossland branch of the International Printing Pressman and Assistants’ Union.19 By the following January, he was co-manager of the biweekly World, then manager and later general manager of the daily World. For the job of editor, though, the miners’ union hired former Miner company president Fred Moffatt.

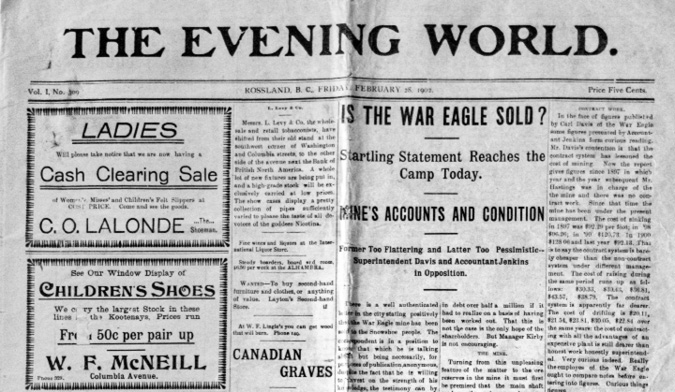

Front page of the World.

Courtesy of the Rossland Museum and Discovery Centre.

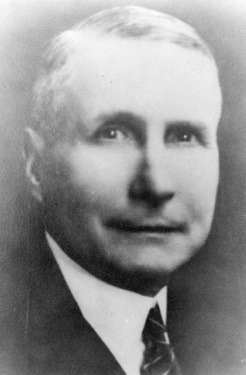

William K. Esling, Rossland’s “Gentleman Journalist” and Rossland Miner owner.

Courtesy of the Trail Historical Society.

Moffatt may have seemed an odd choice. First, he came from a well-to-do eastern Canadian family that had earned its wealth in the insurance business. Second, he had graduated from Osgoode Law School in Toronto, where he practised law for a time. Third, he arrived in Rossland and was soon filing stories as a correspondent for the Toronto Globe. Fourth, Moffatt was no left-wing radical. In fact, for many years after he left Rossland, he was secretary of the Nelson Conservative Association. Lastly, as noted, Moffatt had been president of the Rossland Miner Printing and Publishing Company. Apparently, it was a short-lived appointment, but nevertheless, he had been associated with the World’s journalistic nemesis, the Miner.20 This last item on his curriculum vitae might have seemed an unacceptable liability, given the Miner’s anti-union position under Corbin. After all, Moffatt had served as managing editor of the rival paper.

Rossland Miners’ Union Hall.

Courtesy of the Trail Historical Society.

Where Moffatt was a good fit with the union paper was in his insistence on strict adherence to the federal Alien Labour Act of 1897. Early in his editorship, both that insistence and his legal training would serve the union well. He was also a capable journalist, as revealed in his column, “A Rossland Letter,” in the Globe.21 Colonel Robert T. Lowery, editor of the New Denver Ledge and the doyen of pioneer newspapering in the Kootenays, saw Moffatt as an appropriate professional choice. “He is well-educated, well-connected, gentlemanly in bearing and has good judgement,” Lowery opined.22

While Moffatt remained nameless in the World, his editorial voice was heard loud and clear. Once he perceived injustice, he attacked it tenaciously. His inaugural editorial was unambiguous as to the World’s purpose – it would be a “workingman’s journal, framed particularly to protect and advance his interests,” but it also intended to deliver the news to a “city of busy workers.” Local and mining news would take priority, but Canadian Associated Press telegraphic dispatches would also inform the general public. The daily had an unequivocal “labor interest” but swore to “take an independent stand on all political, municipal and local matters, holding steadily to the credo that ‘the good of the camp’ should ever be the chief consideration of any newspaper hoping to succeed in Rossland.”23

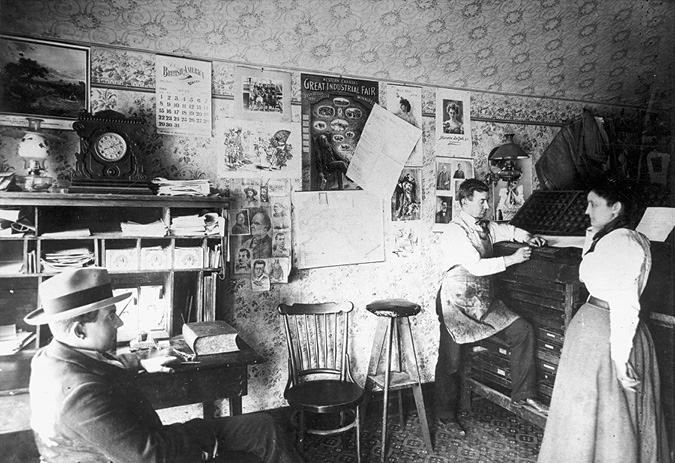

R. T. Lowery (centre) outside his New Denver Ledge office, c. 1897.

Courtesy of Janice (Smitheringale) Wilkin.

As was common in labour circles at the time, the World also attacked Chinese immigrants, stating that the “Heathen Chinee” found no friend or defender at the World.24 Despite the wfm’s constitutional pledge to treat all workers fairly, regardless of race, creed, or colour, the daily jumped on board the anti-Asian movement that was then sweeping the province and would later erupt in the 1907 anti-Asian riots on the BC coast.25

Apart from the Rossland Chinese community, the World made good on its civic pledge from its first issue, critically assessing the mayor and city council and proposing solutions to problems such as sewage, water supply, fire protection, and street repair. It also fulfilled its mandate as a community paper, supplying numerous items of a domestic, social, and cultural nature. In its advertising columns, for example, the householder could learn why they should patronize Thomas Embleton, a grocer who “keeps everything the miner wants to eat.” Those interested in bettering themselves could enrol in C. H. Eshbaugh’s International Correspondence School or visit a planned travelling library.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union presented more personal enlightenment through “The Singing Evangelists” and other entertainment at the miners’ union hall. Church-sponsored events were also listed in the World, as were sporting events such as prize fighting, yacht races, hunting and fishing opportunities, rifle club shooting competitions, and even coverage of cricket matches. The latter catered to the large number of British immigrants among the paper’s readership. A fencing class was offered in Beatty’s Hall – “ladies class a specialty.”26 The International Music Hall brought entertainment to town, but it was not always of a family-oriented nature. The hall’s late-night poker games were popular with young bachelors and could lead to violent incidents. Meetings of social service clubs like the Masons, Ladies of the Maccabees, Elks, and Eagles all got regular mentions.

Workplace fatalities appeared regularly in the World, as did letters home from Rossland volunteer soldiers fighting the Boer War in South Africa. But the World’s true strength, as stated in its mission statement, was as an advocate for the union movement, offering support to the mineworkers of the city and to the growing wfm membership in local mining communities. The paper regularly published reports of labour disputes in the United States – a service that Rossland’s large American population appreciated. Moffatt’s editorial page also offered supportive comments on those disputes, many involving the wfm.

The wfm had earned a reputation as “the most militant” labour organization in the United States, leading several violent strikes in western US mining camps.27 In the World, there was a stream of wire copy on the union’s activities across the mining West, depicting the wfm as an organization “capable of fighting strong and ruthless opponents.”28 James Wilks, the wfm’s Nelson-based representative and a strong campaigner for the eight-hour day for underground miners, was an often-quoted authority. So too was the wfm’s Rossland representative, Chris Foley, an outspoken anti-Asian advocate who became a member of a commission of inquiry studying the so-called Chinese question.29 Smith Curtis, labour member of the legislative assembly representing West Kootenay–Rossland, also received much coverage in the daily, as did plans to support a labour political party.

Despite its attempts to be a well-rounded community newspaper, the World’s arrival on the publishing scene did not merit a mention in the pages of its main competitor, the Miner. However, other members of the local press acknowledged its presence. The Greenwood Miner, for example, welcomed the paper, noting that it “is well patronized by advertisers, neat typographically, gives a full telegraph and local news service, and is independent politically.”30 Iconoclastic Nelson Tribune editor John Houston, often a World ally in future battles with local employers, called it “independent in politics and municipal matters.”31 The Northport News hailed it as a new aspirant for public favours, adding, “It is very neat typographically, is ably edited and is bright and up-to-date locally. It merits the healthy patronage it is receiving.”32 The Moyie Leader called it a “good representative of the working classes, and the miners of the Kootenays should give it their liberal patronage.”33 From farther afield, at Butte, Montana, the Reveille – one of Heinze’s weapons in the copper wars – said the World was “a bright, spicy little paper, [that] is doing valiant service in behalf of justice and fair play.”34

World Defends Labour against Top Stock Manipulator

The daily arrived on the Rossland scene as the union prepared to mount labour’s defence against a formidable international mining investment empire. At the top of that empire sat London-based financier James Whitaker Wright of the London and Globe Finance Corporation. Wright “was adept at manipulating stocks and restructuring his companies, each time adding to his own assets,” writes historian Jeremy Mouat.35 Under the influence of Charles H. Mackintosh, a former lieutenant governor of the Northwest Territories, Wright formed the British America Corporation (bac), which began acquiring mining properties in Rossland. In late 1898, the London financier created the Le Roi Mining Company, originally basing it in nearby Spokane, Washington. A year later he hired Bernard Macdonald to manage the company, with assistant manager William Thompson. Macdonald then hired Bela Kadish to manage the Le Roi smelter in Northport, Washington. Edmund Kirby, the manager of two other bac properties – Rossland’s War Eagle and Centre Star mines – was Macdonald’s equal in opposing unions. The new regime signalled the beginning of a long, troublesome road ahead for Local 38 and the wfm District 6 newspaper.

Newsroom of the Moyie Leader office, c. 1900.

Courtesy of the Columbia Basin Institute of Regional History.

On 25 May, a mere four weeks into its first volume as a daily, the World expressed support for locked-out smelter workers at Northport, about twenty kilometres south of Rossland. With assistance from the Rossland wfm local, the Northport smelter workers had formed a separate local closely tied to the Rossland one. Shareholders had been displeased with the sorry performance of the Le Roi Mining Company, and Macdonald needed to act quickly to sustain their support. He developed a variety of manipulative moves to cut costs. The first was to order Kadish to shut down the Northport smelter for no apparent reason. Speculators suggested that Wright had demanded the shutdown to force stocks down so he could purchase them at the lower rate and then reopen, showing a handsome profit.

Kadish – who, advised by Macdonald, had refused to recognize the wfm as the workers’ bargaining agent – declared, “We have decided to break up the union at any cost. You must abandon your union if you work for us.”36 When the company hired scabs to replace the smelter workers but failed to advise the outsiders of the strike situation, the Northport wfm members advised them to leave. “On learning the true situation,” noted the World, “they walk away, packing their blankets, and cursing those who have made these false representations.” Within two weeks, Pinkerton private detectives were employed, prompting the World to suggest “they may attempt to stir up strife for the express purpose of justifying their employment.”37

James Whitaker Wright, Rossland mine financier.

Rice Belt Journal, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The World predicted that “it is only a matter of time, and of a very short time, when Rossland and the mines here will be brought into the affair.”38 The daily and its union owner were after a quicker solution: “If it should turn out that the whole trouble at Northport was caused by a stock deal and that the employees at the smelter were simply ‘used’ for the occasion, public opinion here will execrate the London management of the Le Roi.”39

Throughout the summer, the Northport dispute competed for coverage with the Boer War, the giant US machinists’ strike, numerous workplace fatalities, and a steady raft of anti-Asian comments. But with Macdonald determined to fight union recognition, Northport served as a prelude to what the wfm was about to face in Rossland. Macdonald, Kadish, Thompson, and Kirby dug in for the long term, while Moffatt, Fletcher, wfm Local 38, and the World girded for battle. Intervening, however, was another union that needed World support: the 5,000 cpr track maintenance workers who had struck for union recognition in June.

As it often did, the paper mobilized its editorial page to take issue with cpr management: “Although the men have not given the slightest cause for any apprehension, a lot of special detectives have been enlisted by the company and the public have been given to understand that the great railway will protect them at all hazards from the violent, bloodthirsty trackmen, who are thus pictured as a class of men who would imperil the lives of the travelling public to gain their end.”40 In September, the World was pleased to report, the strike had won the trackmen union recognition. By that time, however, the Rossland and Northport dispute had become the World’s key focus.

On 11 July, the Rossland miners voted to strike “in sympathy with the Smeltermen’s Strike at Northport and for $3 per day for shovelers [muckers] and carmen and to adjust other differences.”41 The next day, between 1,200 and 1,400 miners walked off the job, with the World’s full support. Even its ads from local businesses offered strikers material assistance in the form of credit and reduced prices. The paper reported that the Rossland News Boys Union refused to deliver the Miner, which, along with the Rossland Board of Trade, articulated the main public opposition to the strike. The newsboys then struck in sympathy with the miners’ union.42

In its 16 July edition, the World charged that the mine managers and owners were using espionage, a blacklist of supposed agitators, and a squad of Pinkertons to stir up dissension. Although it would take much of the summer to unravel the labyrinthine ownership and investment structure of the Le Roi Mining Company, the World made a valiant effort. In response to the suspicious financial dealings of Wright, and Macdonald’s resolve to destroy the union, the World developed a rhetorical arsenal to convince its readers that the mine managers were union busters, violators of Canadian laws, and stock manipulators.

In both the Northport situation and at Rossland, the paper also showed its hostility – and that of the wfm members – to scabs, calling them “skunks” and traitors.43 On several occasions during the long strike, scabs were arrested for carrying firearms. In late July, Northport smelter imported scabs from Leadville, Colorado, who “were well guarded by a posse of armed men led by a man who declared he was a United States marshall and who promptly pulled his gun and called on his armed assistants to do the same, when the union agent approached the gang.”44 The World reported that smelter manager Bela Kadish “had openly defied the law at Northport and had armed himself and his men and so equipped had openly paraded the streets of the town.”45

The union took steps to address the problem of imported foreign workers. As with the Northport situation, the Rossland local approached potential scabs and warned them off. Swedish miners disclaimed any connection with known scabs, declaring that “their men are union men good and true.”46 In a letter to the editor, one of the Italian union members at Rossland rejected suggestions that there were Italian scabs: “You cannot find one of our lot in the ranks of the scabs or working against the union in any way.”47

Some contributors to the World expressed their feelings about scabs in verse. In a poem titled “The Moral Leper,” a “Watch Case Engraver” wrote,

To be a Scab! O brothers, think

How base the nature that would sink

To such a depth of infamy!

Consider what it means, O ye

Who weakly falter at the brink.

It rather sever every line

To love or life, nor would I shrink;

Nor take – by God – a kingdom’s fee

To be a scab!48

Another sarcastic poem, called “Scabbies’ Lament,” feigned sympathy for scabs:

It’s a serious problem

That stares in the face;

To blend with common strikers

Would be to use sheer disgrace.

We have proved ourselves heroic,

And our friends have paid us well;

Though they dare not blow the whistle,

Gladly we obey the bell.”49

That this latter poem was written in the strike’s third month, with no end in sight, perhaps explains its more cynical tone.

The World adopted a legal line of defence on behalf of the strikers, calling attention to the mine managers’ violations of the law. It argued, for example, that the 1899 eight-hour law was not properly enforced and that mine owners took advantage of it. The Mine Managers’ Association complained to the federal government about the unfairness of the law and other “offensive and obnoxious” legislation.50 They lobbied the BC legislature to have the law repealed but with no success. Still, the violations continued. But the greatest insult was the mine owners’ persistent attempts to hire workers from the United States and abroad in violation of the federal Alien Labour Act. In fact, the hopes of the striking Rossland union were pinned on the federal government’s stopping mine owners from engaging “bogus employment agencies seeking to flood the over-crowded labor market with cheap foreign labor.”51

In August, the World chided Macdonald, the Le Roi manager, for seeking an injunction against strikers through US courts. “The result,” World editor Moffatt argued, “will make the fight now in progress all the more bitter and prolonged. Manager Macdonald is fighting for his official life and will evidently hesitate at nothing to gain his point unless – unless his shareholders stop him.”52 A later editorial argued that union men would not be dismayed by the “unfair injunction obtained by Bernard Macdonald from the United States court at Seattle … The whole proceedings from the start are a fair sample of the way a big corporation will evade and twist the law for its own evil purpose.”53 In mid-September, the World reported that mine manager Edmund Kirby’s company had sued the miners’ union for $25,000 to cover damages during the strike.

The World also turned to the police courts in its battle against what it saw as the tyranny of the managers. When Joseph Colistro and Thomas Beamish were arrested for allegedly intimidating Joseph Horn by publicly calling him a scab and attacking him, the World wrote in their defence. This attempt to cast the two accused men in a sympathetic light had no effect on the judge, who found them guilty and sentenced them to two months in the Nelson jail with hard labour. While Moffatt admonished readers to avoid violence, he argued that perhaps the judge was too harsh. Yet the trial afforded the union’s paper an opportunity to expound on the problem of violence and how the hiring of scabs perpetuated it. As wfm Local 38 official Frank E. Woodside noted, “The union men knew how the game was played, which was to get some of the spotters [management supporters] to stir up trouble and cause a fight and then get the union men blamed for it.”54

The Miner was often Moffatt’s key target, and he seldom missed a chance to expose it as Macdonald’s union-busting mouthpiece. Initially, it was not clear that Macdonald had bought the daily, until Heinze announced the sale. It soon became clear that Macdonald was playing at Heinze’s old game of using the local press to support his schemes, but not all local papers were on side. For example, the World won support from Nelson Tribune editor John Houston, who had long cultivated a reputation as a left-wing irritant to companies and governments. “The Evening World, without a dollar behind it,” Houston wrote, “is making a much better fight for the miners’ union of Rossland than the Miner, with all the Le Roi company’s credit backing it, is making for the mine managers. It is simply a case of brains against an overdrawn bank account.”55 The Grand Forks News added its voice, along similar lines: “The Rossland Miner has been ensmalled [reduced in size]. The labor troubles in that camp have pinched it to a seven-column folio, but its general appearance has been improved. That cannot be said of its character.”56

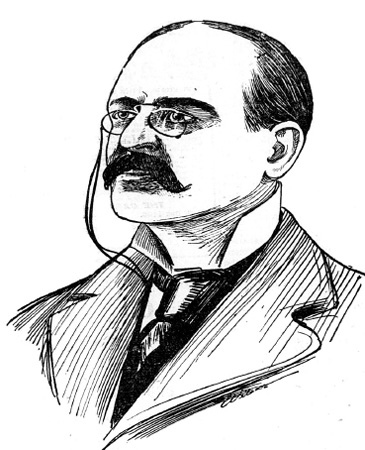

John Houston, Nelson Miner editor.

Courtesy of the Nelson Museum of Art and History.

Letters to the editor conveyed the anger and dismay of workers and their families as the strike continued. G. Eeser offered his views, arguing that Macdonald is not a “union wrecker” and a “union smasher.” Instead, “Mr. Macdonald will smash nothing but the mining companies employing him, and the business interests of the community.” Eeser then likened the company manager to “foolish old Don Quixote, who vainly essayed to restore Knight Errantry”; he will meet “only with ignominious defeat at the hands of the Miners’ Unions.”57

By late August, the World was spreading rumours about the dismissal of Macdonald, Kadish, and bac head Wright. Moffatt employed a new device on his front page: the overheard telephone call supposedly reported verbatim. It was meant to be humorous, featuring Macdonald having a chat with his underlings Thompson and Kadish, but it was not reliable information. Rumour had it that Henry Bratnober, a San Francisco mining engineer for the Le Roi mine, and E. B. Braden, former manager of the mine at Helena, Montana, were in town to oust Macdonald – whom the World called “a little tin god.”58

Another new arrival was “Al Geiser, a geezer of Oregon – accompanied by five men,” the World reported, who “proposes to work the Le Roi mine on contract and the manager has brought him here to use him against the strikers and to get over the alien labor law difficulty.”59 With all the comings and goings of the company’s henchmen, the World hoped that someone would “unwind the tangle.”60 That someone was thought, for a time, to be Robert J. Frecheville, an English mining engineer that the Le Roi board of directors assigned to investigate the situation. It was another false hope.

In early September, Moffatt reported more violations of the Alien Labour Act, declaring, “We have no room in Canada for the alien law breaker.”61 By Labour Day, the World had devoted much of its front page and most of its editorial page to badgering Wright, Macdonald, and Kadish – the trio it had labelled enemies of trade unionism. Macdonald had become the “Chronic Deceiver,” who has “conspired to produce disruption.”62 Later the World would have additional nasty names for Macdonald, “the union wrecker, cheque waver, and ex-manager,” who was also a “blatherskite,” a “serpent,” and a “standing menace to the Rossland camp.”63 Miner editor Gregg suffered abuse from Moffatt for doing Macdonald’s bidding, but the Miner editor shot back: “The World has suggested the literal assassination of Mr. Macdonald and should be held responsible accordingly.”64

The World exposed Macdonald’s scheme to import 150 to 200 men by circulating copies of the Miner, so that the “alien contract labour” will be “deceived and cajoled” to come to Rossland. The community was urged to “struggle against Barneyism” – another denigrating name for Macdonald and his anti-union actions.65 On a more positive note, the World was pleased to report, the local magistrate found Al Geiser guilty of violating the Alien Labour Act and fined him $550.66

Yet, more scabs continued to arrive in Rossland, and attempts to stop them were barred by a court injunction. As the World put it, the impact of the injunction was “to hand over to the employers a legal club with which to fell a defenceless class in the community.”67 It was no coincidence that unemployed men had migrated to Rossland and Northport; agents had enticed them with false promises and lies about the strike being over. Such rumours were being spread by former Rossland police chief John Ingram, now a “scab herder for the Le Roi mines.”68 Ingram had even recruited sixteen Doukhobors – members of the Russian immigrant sect that had immigrated to Saskatchewan in 1898 and would move west to the Kootenays ten years later. As the World reported it, “The Le Roi management has fallen back on Doukhobors, men who cannot speak a word of English, and who were imported into this country as farmers pure and simple.”69 Now another immigrant group would join the Chinese and Japanese as pariahs of the labour movement.

By November, a “miscellaneous herd of Missourians and general hoboes” had formed a scab union at Northport “for mutual protection.”70 There was good reason for this, given that Kadish, the Northport smelter manager, had authorized the brandishing of weapons in the streets with the result that at least one man was shot. The arrival of scabs persisted throughout November, and Moffatt correspondingly increased the intensity of the World’s outrage. As always, his first target was the Miner: “Mr. Macdonald’s paper has a laudatory clipping on ‘Kaffir Miners.’ Is the Great Man after Kaffirs as muckers? Kaffirs, Doukhobors and Missourians are all good for the camp.”71 With Frecheville continuing his investigation of the Le Roi mines and smelter, Moffatt advised him to “muzzle the Miner forthwith or that charming publication will unquestionable [sic] prolong the dispute and prevent the possibility of any advancement.”72

The World turned to the London press to learn of the imminent end of the “rascality of Whitaker Wright in his many nefarious transactions particularly with Rossland properties.”73 Moffatt also learned that Macdonald, a.k.a. “Mr. Trouble Maker,” would soon be replaced and that he was trying to influence the new manager, John H. MacKenzie. Kadish supposedly would leave as well, once Frecheville released his report. Despite these claims, the two managers remained in place.

Frecheville’s report was slow in coming; nevertheless, it would seem from the World’s coverage that the local miners’ union remained strong and in good spirits. Toward the end of November, the World reported on a banquet the union held in honour of Colistro and Beamish upon their release after serving their two-month sentences for attacking a scab. The festive event opened with a crowd of 625 miners singing “The Northern Mine Workers’ Union” to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne”:

Shall song and music be forgot

When workingmen combine,

With love united may they not

Have power almost divine

Shall idle drones still live like kings

On labors not their own,

Shall true men starve while thieves and rings

Reap what they have not sown

No, by our cause eternal no.

It shall not forever be,

And union men will e’er long show

How the workers can be free.74

Mackenzie King Arrives in Rossland

Several times over the course of the strike, the World tried to convince readers of the virtues of conciliation and arbitration for resolving labour disputes. It counselled Frecheville to recommend a system similar to the one adopted in 1896 in New Zealand, the “paradise of the Working Man” and “a country without strikes.”75 Eventually, Moffatt conceded that changes in the federal Conciliation Act would be necessary if arbitration were to work in Canada. The law only allowed an arbitration hearing if both sides agreed to it, and the Rossland and Northport managers were not interested.

It would take until November before the federal government sent an investigator who the wfm hoped would settle the strike once and for all. The leadership would be sorely disappointed. When deputy labour minister William Lyon Mackenzie King arrived on 7 November to assess the situation, he initially seemed sympathetic to the union. The World argued that King “will have no trouble ascertaining … that the law was openly, willfully and outrageously violated by the mining companies.”76 The union was displeased to learn that King was of the opposite opinion and would return to Ottawa with an anti-strike message and no proposal for an investigation to study violations of the law. “The situation [in Rossland] is one of the grossest tyranny of a labour organization,” wrote King to a friend, “and the dealings of those who have manipulated the affair are as crooked as they can be.”77 He might have been describing the mine owners, as far as the wfm was concerned; instead, he was talking about the leaders of Local 38 and wfm District 6.

According to King, the strike “was not declared at the wish or by the vote of the workers in the Rossland mines themselves, but was … forced upon them by subterfuge and a great deal of crooked work on the part of the executive committee.” For the federal government “to do anything which would strengthen the hands of these men” would be “unrighteous and disastrous.” Clearly, the deputy labour minister had lost whatever sympathy he had brought to Rossland for the union and was convinced that the miners’ “cause is gone & they know it.”78 King advised the union to call it quits and left town. It was not the last time King would side with the employer in labour disputes.

William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1899.

Library and Archives Canada, C-014191, via Wikimedia Commons.

Historian Paul Craven suggests that King’s turn against the Rossland miners was rooted in his support for the American Federation of Labor (afl) and its founder, Samuel Gompers. At its 1902 convention in Kamloops, the wfm officially endorsed socialism and formed the American Labor Union (alu), an organization that promoted industrial unionism. District 6 joined the fight against the afl’s exclusive craft unionism by quitting the Trades and Labour Congress. Gompers labelled the alu dual unionism, and King apparently agreed. Even at this early stage of his career, the future prime minister “praised American labour leaders who ordered an end to Canadian strikes against the will of the local membership.”79 Clearly, the Rossland strikers were at a disadvantage with King, who saw the afl as the most politically profitable organization to support.

The World’s political focus was more local. In November, it shared the news that the miners’ union and others had formed the Labour Municipal League with plans to run a candidate for mayor and aldermanic posts in three wards in the coming Rossland election. In early December, a lecture on Christian socialism seems to have inspired political activity in Northport, where the union’s socialist ticket won all but one seat. That victory emboldened the striking smelter workers.

J. M. Cameron, the BC organizer for the Socialist Party of Canada, spoke at the miners’ union hall, calling for “public ownership of private trusts” as a way to “remove the cause of industrial strife.”80 Kootenay miners were a receptive audience. “Socialists played an important role in the locals,” McCormack explains, and international wfm president Ed Boyce was said to be under the influence of famed American socialist leader Eugene V. Debs.81 The World scoffed at the Miner’s slamming of Liberal labour legislator Smith Curtis, a Rossland lawyer and mine operator, for supposedly “having anarchist sentiments.” The World sarcastically commented, “We welcome him into the ranks of the bad, bad men whose record for lawlessness, brutality and all other crime stands revealed to a suffering community by their actions during the months in which this industrial war has so far dragged along.”82

Rossland strikers increased their numbers when the union executive ordered mineworkers to down tools at the War Eagle and Centre Star mines, owned by the Toronto-based Gooderham-Blackstock group but separate from the Le Roi.83 But the local strikers’ biggest boost came from wfm vice-president James Wilks. Returning from the wfm executive meeting in Denver, he reported that the union executive “have made all necessary plans and preparations to continue the fight indefinitely, until justice is done and the mine laborers at Rossland receive $3 per day, the same rate as paid in every other camp in the Kootenay and Boundary countries.”84 Further support came from Houston at the Nelson Tribune when he predicted that “mine workers and smeltermen will win in the end, because they have right on their side.”85

The New Year brought strikers a welcome gift from the Vancouver Trades and Labour Council: it voted to boycott Gooderham & Worts whiskies until the Rossland strike ended. As mentioned, the Gooderham and Blackstock syndicate owned Rossland’s War Eagle and Centre Star mines. But there was bad news from the wfm international office in Denver. Despite Wilks’ pledge, it now claimed it was unable or unwilling to fund the strike any longer. Coupled with the disappointing King report in the Labour Gazette, that news put a damper on miners’ hopes for a favourable end to the strike. The World resumed its usual coverage of mining news and ore markets but continued to warn of the destructive use of scabs. On 2 January, it noted that King would not file a report on the strike because the mine managers had refused to co-operate with his investigation.

Meanwhile, the World turned its critical eye on Rossland mayoral candidate John Stilwell Clute, a local lawyer and aldermen since 1898. Clute would soon be accused of accepting a “rake-off” from professional gamblers.86 As Alderman Clute began building his electoral machine, the World called him the “candidate of the ringsters” and accused him of a “closed door policy.”87 According to the World, “Mr. Clute has already shown that he is prepared ‘to look the other way’ when convenient, and that he is quite prepared to administer his share of the police business with due regard to the interests of his ‘friends.’”88 When the Miner endorsed Clute, the World sided with labour candidate Peter John McKichan and linked Clute to the “dictators.”89 Assuredly, this referred to the mine owners. A World letter writer added that Mr. Clute was “merely a tool in the hands of an attempted political combine which had the spoils of offices only in view, and whose real desire was to force their nominees on the rest of us.”90

The World advised voters to “try an independent mayor, even if he happens to be a working man.”91 It was editor Moffatt’s last shot at opposing Clute’s candidacy. Predictably, he charged the Miner with undermining the election: “That journalistic calamity peddler, the Whiner, has done its best to scare the voters into the belief that unless Mr. Clute is elected they will wake up to see wall-eyed ruin staring them in the face.”92 Nonetheless, the 16 January vote was close – 455 to 393, with Clute beating McKichan by only 62 votes. Clute voters elected aldermen in two wards, labour in one. The wfm newspaper congratulated the labour party for putting up a “plucky fight.”93 It also promised to devote much space to municipal affairs in future. The election was a turning point for labour, for it now was a clear player in Rossland municipal politics and had inspired future participation by labour candidates for mayor and council. Other towns would follow its lead.

Four days after the election, on 20 January, the World reported that the mayor’s gavel had been handed to Clute. The daily was, indeed, looking to the future when Moffatt reminded Clute and his council that it would be watching the economic situation for signs that the new mayor will “straighten matters out.”94 It promised to give the new council a fair shake if it did the same for the community.

World Fights Perceived City Council Corruption

On 24 January, wfm Local 38 secretary Frank E. Woodside announced that the Le Roi mine and smelter strike was over. He gave no details of the settlement and stressed that the other mines were still on strike, which prompted him to warn out-of-town job seekers to stay away. Even with the settlement, the World’s animus against its journalistic enemy remained active.

In the ongoing battle over financial honesty at city hall, the provincial government fanned the political flames by appointing Frank J. Walker, a Clute nomination, to serve as Rossland police commissioner. The move indicated to the wfm leadership that Clute’s Rossland would be wide open to the kind of activity the local temperance union and other social reformers opposed. The World pleaded for an avoidance of New York’s Tammany Hall–style rule, alluding to the perpetrators of long-standing city corruption in the US metropolis.

“Mr. Clute is a weakling at best,” the daily concluded in early February, “and as mayor of Rossland, is merely a tool in the hands of as unscrupulous gang of ringsters as exist in Canadian civic circles today.”95 The coup de grace was the appointment of John Ingram, the city’s former police chief and, more recently, a scab hunter for the mine owners. As historian Ron Shearer notes, Ingram displayed a “bad temper and bad behaviour”; he was a man who engaged in “all kinds of dissipation while under the cloak of authority.”96 With the local law in Ingram’s hands, it must have seemed more than ever to the World that Rossland had reverted to the bad old days of 1897.

Perhaps worse, the London court trying Wright acquitted the financier of manipulating mining stocks. “An official investigation appointed in early 1902 to examine the convoluted dealings of Wright’s companies made no recommendation to prosecute him,” Mouat notes, adding, “Wright’s connections with Britain’s traditional elite were rumoured to underlie the government’s leniency.”97 He “has risen to victory from the depths of defeat,” the World reported in what must have been a deeply disappointing moment, and he is “again on top in the Le Roi Company.”98 With Wright’s exoneration, Macdonald was restored to his previous role as manager of the mine and Northport smelter. The settlement terms at Rossland’s Le Roi mine were still not announced, but the return of Macdonald did not bode well. How long the miners at Rossland’s War Eagle and Centre Star stayed on the picket line is unclear, but the withdrawal of wfm financial support, and the return to work of Le Roi miners and Northport smelter workers, worked against continuing the dispute. Also undermining a positive outcome for the union might have been the 1900 Taff Vale case in Britain that allowed corporations to sue unions.

The end of the Rossland strike did not spell the end of the World. In fact, Moffatt, Fletcher, and the paper’s staff continued to vigorously support labour struggles in the Kootenays. For example, passage of BC’s Trade Union Protection Act in 1902 was hailed by the paper as a breakthrough in preventing lawsuits like that of the War Eagle and Centre Star mines against the wfm. In many respects, the World sustained its mandate to “advocate the cause of organized labor.”99 But the daily presented a false front to its readers, for all was not well with the union.

When, in April 1902, wfm District 6 held its convention in Kamloops, the World called it “a great success.”100 It advised the gathering on the need to build a strong political party and published a labour political platform. It was no surprise to see the convention call for compulsory arbitration, public ownership of transportation and communications, and the abolition of Asian immigration. The international convention held in late May would be a different matter, as debate about the Rossland and Northport strikes was acrimonious. “The strike at Rossland was a complete failure,” wfm president Ed Boyce, once a vocal Rossland supporter, reported. “The same is true of the lockout at Northport.”101 Wilks had resigned as president of District 6 but stayed on the wfm executive and attended the convention. He did not sign the convention executive report about Rossland, saying that he disagreed with its endorsement of socialism, not its critique of the Rossland strike. The Rossland executive blamed Boyce and the international wfm executive for the failure of the strike, but coverage of the debate did not appear in editions of the World published during the convention.

The 1903 Royal Commission on Industrial Disputes in British Columbia blamed outside agitators for the troubles in mining districts like Rossland.102 The evidence presented in the World suggested otherwise. The paper argued that the federal government’s failure to enforce the Alien Labour Act and the provincial government’s unwillingness or inability to enforce the eight-hour law were closer to the real causes of labour unrest. Mine owners including former premier James Dunsmuir joined the chorus of anti-union owners who had vowed never to accept unionism, and the failed strikes at Rossland and Northport only strengthened their resolve.

Despite fin de siècle Rossland being a hotbed of labour unrest, its unions had largely lost the struggle with the local mine managers and their shareholders in London and elsewhere. Yet local wfm leader Chris Foley proudly summarized the union struggle in a letter to the World: “I hardly know which to admire most, the spirit of self-sacrifice displayed in coming to the aid of a sister organization battling against tremendous odds, or the loyal manner in which the union responded to a man when called upon to register a protest against the petty tyranny and injustice that has characterized the action of the mine management.” He concluded that the union adopted the only course left open to it. “To have submitted [to the employers] … would have branded them cowards in the eyes of organized labour.”103 For Mouat, “class struggle was not an abstract notion but an accurate description of British Columbia’s industrial relations. Their strikes lost and their policies discredited, the moderates within the wfm were replaced by more militant and radical leaders.”104

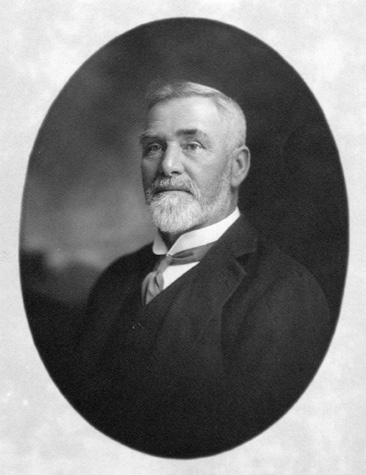

James Dunsmuir.

Courtesy of the City of Victoria Archives.

On 1 May 1902, the World congratulated itself on its first anniversary, noting that its “prospects are brighter now than they were on May 1st, 1901, its usefulness to the community is sufficiently demonstrated. The year just past has been a trying period to every person in the camp. Never in its history has public sentiment been so divided, and never have its common interests been so neglected,” the daily noted. “That a paper, which should be a mirror of public opinion, should prove itself a success under such circumstances argues well for its management and for its future prosperity.” It also said farewell to its first editor. “No small measure of that success is owing to the untiring efforts of the late Editor, Mr. Fred C. Moffatt, whose endeavors to promote a right understanding of the warmly debated points at issue eventually broke him down in health. His cool judgment has more than once averted trouble, and the thanks of the community as well as of the proprietors of this paper are alike due him.”105

The World’s war with the Miner did not abate after the strike. For a time, the World continued to voice its support of the miners and sustain its criticism of the mine owners and their paper.106 Fletcher carried on as World manager until 30 June 1904. A month later, the World’s role in shaping working-class political opinion in the Kootenays was silenced without a murmur of explanation.107

Ginger Goodwin Leads Trail Strike

With the miners’ strike over in Rossland, the labour movement was subdued for a time. wfm Local 38 was soon joined by Local 105 at the Trail smelter, but unsettling labour relations did not reach fever pitch again until 1917, when smelter workers, led by socialist Albert “Ginger” Goodwin, struck for the first time since the giant Trail operation began in 1896. As it turned out, in Rossland – with Moffatt’s editorial pen laid to rest, with the demise of the World Publishing Company, and with the wfm’s Rossland locals defanged by their international parent and struggling to survive – one of western Canada’s earliest labour dailies quietly disappeared into the largely unsung annals of Canadian labour journalism history.

Over the course of its run, the World offered readers a daily reflection of working-class values and views that allowed its publisher to effectively counter the propaganda issuing from the mine owners’ press. Loyalty to the union and one’s fellow workers was a central value, but so was the collective welfare of the community, the “good of the camp.” The paper articulated a clear sense of fairness, arguing for the equal application of the law but recognizing instances in which the scales of justice were hopelessly tilted in favour of the corporate owners. Indicative of this tilt is the fact that it was a court decision that ultimately led to the paper’s disappearance.

The ultimate legacy of the World is unknowable, but clearly its ideas and advocacy found a receptive readership. The paper had urged political action, on a local level, to elect labour candidates, and soon after its run, socialist politics began to challenge the Conservative and Liberal hold on Kootenay voters. Perhaps the daily also served as an inspiration to later efforts – such as the Fernie Ledger, purchased by United Mine Workers District 18 in 1909 in the East Kootenay district. Further afield, it is possible that the Rossland experiment was remembered by the leaders of the much later Glace Bay Gazette, bought by United Mine Workers District 26 in far-off Nova Scotia.108 In the end, perhaps the World’s greatest legacy is simply as a reminder that when a band of determined workers muster the courage to challenge a daunting enemy, a daily newspaper can be a vital weapon in the fight for workers’ rights.

Several people assisted in the research for this article. Historian Ron Shearer has opened many doors to Rossland history, and his work has immensely benefitted the rest of us. Researcher Sarah Taekema at the Rossland Museum and Discovery Centre also deserves thanks for her perseverance in combing through the bound volumes of the Rossland Miner at my request. I’m also indebted to Kootenay historian Greg Nesteroff, whose dexterity with online archival files never ceases to dazzle me. Marc Zwelling, a former trade union staff member, provided wise editorial advice, as did labour historian Gregory S. Kealey and Labour/Le Travail editor Kirk Niergarth. Finally, thanks to the peer reviewers for their critical reading of earlier drafts.

1. Harold Kingsmill, First History of Rossland, BC (Rossland, BC: Studnen & Perrine, 1897), 8.

2. “Editorial Notes,” Rossland Evening World (hereafter rew), 6 May 1901, 2.

3. The Nanaimo Daily Herald, a morning paper, first appeared on 1 March 1901 and quickly became the official organ of the Nanaimo Labour Party. It thus predated the World by two months but soon ceased to be owned and operated by the Nanaimo Miner’s Union. The Evening Palladium in Hamilton, Ontario, predated the World by fifteen years; appearing at the end of 1886, it only survived for a few issues and covered mostly central Canadian labour news and issues. Several weeklies also performed that task, starting with the Ontario Workman in the earlier days of the labour movement and its fight for a nine-hour workday. Not until 1894, though, did Winnipeg’s People’s Voice appear to represent the labour movement in the Canadian West. These weeklies are the primary sources that provide workers their own voice in describing the episodes that mark working-class history and are critical to understanding labour’s past. But despite that proud heritage, throughout much of the next century, Canadian labour leaders dreamt of founding a labour daily to counter the persistently negative images of labour in the media. “Holiday Number,” Nanaimo Labour Herald, 1903 (exact date unknown); Ron Verzuh, Radical Rag: The Pioneer Labour Press in Canada (Ottawa: Steel Rail, 1988), 58. See also David Buchanan, Red Flags: The Early Labour Press in Canada (website), https://prolitca.wordpress.com.

4. The description of Rossland citizenry is from Garnet Basque, West Kootenay: The Pioneer Years (Surrey, BC: Heritage House, 1990), 71. The population figure is from Jeremy Mouat, Roaring Days: Rossland Mines and the History of British Columbia (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1995), 116. Mouat notes that Rossland’s total population of 6,132 was two-thirds male, quoting the 1901 Census of Canada.

5. A. Ross McCormack, Reformers, Rebels and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement, 1899–1919 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1977), 17.

6. Robert Babcock, Gompers in Canada: A Study in American Continentalism before the First World War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974), 134.

7. A review of the University of British Columbia’s online historical newspapers collection (specifically, https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/bcnewspapers/satworld) shows that the World published off and on until mid-1904. On 30 August 1903, it stopped appearing for a time and did not continue as a daily until mid-December. Between 28 August and 15 December 1903, it reverted to an eight-page weekly known as the Saturday World. The collection then ran from January to the end of June 1904. This review benefitted from having access to the online system, allowing for a more thorough perusal of the daily. Previously, few labour historians had such easy access to the history buried in the World.

8. Front-page banner, Industrial World (hereafter iw), 23 September 1899, 1; iw, 20 January 1900, 1.

9. “Not to Tear Down,” iw, 23 September 1899, 2. According to the paper’s masthead, Flynt was the first editor. Alexander Charles Thompson replaced him in April 1900 and ran the paper mostly as a biweekly until January 5, 1891. After that, William Verran and James Hamilton Fletcher took over until the paper went daily. All the editors appear to have come from printing backgrounds and would have been members of the typographical union.

10. iw, 23 September 1899, 2.

11. Ron Shearer, “Eber Clark Smith, Biographical Notes,” version 6, June 2018, compiled from research by Gil Boehringer, Greg Nesteroff, and Ron Shearer.

12. “Editorial Notes,” rew, 8 May 1901, 2.

13. McCormack, Reformers, Rebels and Revolutionaries, 35–36.

14. “Editorial Notes,” iw, 3 March 1900, 2.

15. “Our First Issue,” rew, 1 May 1901, 2.

16. The wfm, headquartered in Denver, Colorado, published the union’s official organ, the Miner’s Magazine.

17. Gerald R. Boucher, “The 1901 Rossland Miners’ Strike: The Western Federation of Miners Responds to Industrial Capitalism,” ma thesis, University of Victoria, 1986, 14.

18. Boucher suggests that Alex Thompson “was hired by the wfm to edit and manage the Evening World.” However, this is not accurate. Thompson had edited a biweekly version of the World until early 1900. He identified himself as editor of the daily World during testimony before the 1903 Royal Commission on Industrial Disputes in British Columbia. Here, however, Boucher suggests that “the accuracy of Thompson’s statements is questionable” and that his “testimony must be viewed with some skepticism.” Boucher, “1901 Rossland Miners’ Strike,” 39, 41.

19. “Pressman’s Union,” Rossland Weekly Miner, 23 August 1900, 3.

20. “Fred Moffatt, Local Lawyer, Dies, Hospital,” Nelson Daily News, 11 September 1928.

21. For a sampling, see “A Rossland Letter,” Globe, 18 February 1897, 4.

22. “Rossland Change of Editors,” New Denver Ledge, 2 September 1897, 4.

23. rew, 1 May 1901, 2.

24. “Heathen Chinee,” rew, 24 June 1901, 1.

25. See Julie Gilmour, Trouble on Main Street: Mackenzie King, Reason, Race, and the 1907 Vancouver Riots (Toronto: Penguin, 2014). See also David Goutor, Guarding the Gates: The Canadian Labour Movement and Immigration, 1872–1934 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008).

26. “Sports,” rew, 3 May 1901, 3.

27. American labour historians Selig Perlman and Phillip Taft in Sidney Lens, The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sitdowns (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, 1972), 133, cited in Boucher, “1901 Rossland Miners’ Strike,” 17.

28. McCormack, Reformers, Rebels and Revolutionaries, 39.

29. This commission, the Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration, was known as the Clute Commission after its chair, Toronto lawyer R. C. Clute.

30. “Editorial Notes,” rew, 7 May 1901, 2.

31. [Untitled], rew, 4 May 1901, 4.

32. “Editorial Notes,” rew, 10 May 1901, 2.

33. “Editorial Notes,” rew, 15 May 1901, 1.

34. “Notes and Comments,” rew, 19 July 1901, 2.

35. Mouat, Roaring Days, 52.

36. “A Fair Comparison,” rew, 21 August 1901, 2.

37. “Pinkerton Men,” rew, 8 June 1901, 2.

38. “Compulsory Arbitration,” rew, 8 June 1901, 2.

39. “A Stock Deal,” rew, 30 May 1901, 2.

40. “C.P.R. Strike,” rew, 20 June 1901, 2.

41. “The Le Roi Mines,” rew, 11 July 1901, 1.

42. “Striking Miners,” rew, 15 July 1901, 1. A few years later, when he fought the copper wars in Butte against his two archrivals, William A. Clark and Marcus Daly, Heinze bought the Butte Reveille and used it to gain workers’ support.

43. “Notes and Comments,” rew, 12 July 1901, 2.

44. “Smelter Army,” rew, 29 July 1901, 1.

45. “Breaking the Law,” rew, 30 July 1901, 2.

46. “Not a Swede,” rew, 29 July 1901, 1.

47. “Are Good Union Men,” rew, 30 July 1901, 1.

48. “The Moral Leper,” rew, 9 August 1901, 2.

49. “Scabbies’ Lament,” rew, 17 September 1901, 3.

50. “Great Burdens,” rew, 26 July 1901, 1.

51. “A Plain Statement,” rew, 29 July 1901, 4.

52. “The Latest Move,” rew, 2 August 1901, 2.

53. “Twisting the Law,” rew, 5 August 1901,2.

54. “Colistro Case,” rew, 15 August 1901, 2.

55. “Notes and Comments,” rew, 10 August 1901, 2.

56. “Notes and Comments,” rew, 13 August 1901, 2.

57. “Communication,” rew, 29 August 1901, 2.

58. “Notes and Comments,” rew, 26 August 1901, 2.

59. “Al Geiser,” rew, 26 August 1901, 4.

60. “The Situation,” rew, 28 August 1901, 1.

61. “The Geiser Case,” rew, 17 September 1901.

62. “A Chronic Deceiver,” rew, 3 September 1901, 2.

63. A “blatherskite” is a person who talks a lot but says little. “A Blatherskite,” rew, 9 November 1901, 2; “Macdonald’s Misleading Tactics,” rew, 4 September 1901, 1.

64. “Mr. Macdonald’s Paper,” rew, 13 September 1901, 2.

65. “The Situation,” rew, 4 September 1901, 2.

66. “Convictions under the Alien Labour Law,” Labour Gazette, August 1903, 144.

67. “Injunctions,” rew, 24 October 1901, 2.

68. “A Prize Scab Herder,” rew, 2 October 1901, 2.

69. “A Valuable Haul,” rew, 22 October 1901, 2.

70. “Queer Smelter Situation,” rew, 8 November 1901, 1.

71. “Notes and Comments,” rew, 6 November 1901, 2.

72. “Muzzle the Miner,” rew, 1 October 1901, 2.

73. “Will Wind the Rascal Up,” rew, 14 November 1901, 1.

74. “A Great Demonstration,” rew, 30 November 1901, 1.

75. “How It Works,” rew, 21 October 1901, 1.

76. “Mr. King’s Report,” rew, 15 November 1901.

77. Mouat, Roaring Days, 102.

78. As quoted in Mouat, Roaring Days, 101–102.

79. Paul Craven, “An Impartial Umpire”: Industrial Relations and the Canadian State, 1900–1911 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980), 134–135.

80. “Their Platform,” rew, 7 December 1901, 1.

81. McCormack, Reformers, Rebels and Revolutionaries, 40–41.

82. “Kicked Out?,” rew, 2 December 1901, 2.

83. Mouat, Roaring Days, 44.

84. “To Be a Fight to a Finish,” rew, 3 December 1901, 1.

85. “Will Fight On,” rew, 5 December 1901, 2.

86. “Wide Open,” rew, 16 December 1901, 2.

87. “He Must Face the Music,” rew, 13 January 1902, 1.

88. “What He Has Done for Us,” rew, 11 January 1902, 1.

89. “City Finances,” rew, 11 January 1902, 2.

90. “It Will Not Do,” rew, 11 January 1902, 1.

91. “A Labor Mayor,” rew, 13 January 1902, 2.

92. “Must Choose,” rew, 15 January 1902, 2.

93. “The Election,” rew, 17 January 1902, 2.

94. “The Election,” rew, 17 January 1902, 1.

95. “The Sediment.” rew, 1 February 1902, 2.

96. Ron Shearer, Chicanery, Civility and Celebration: Tales of Early Rossland (Rossland, BC: Rossland Heritage Commission, 2019), 81–83.

97. Mouat, Roaring Days, 61.

98. “Wright Is in Control,” rew, 1 February 1902, 2.

99. rew, 1 May 1901, 2.

100. “Kamloops Meeting,” rew, 12 April 1902, 2.

101. Proceedings, Tenth Annual Convention of the Western Federation of Miners of America, Denver, Colorado, 26 May–7 June 1902, 16.

102. Canada, Report of the Royal Commission on Industrial Disputes in the Province of British Columbia (Ottawa, 1903).

103. “Communication,” rew, 13 November 1901, 3.

104. Mouat, Roaring Days, 108.

105. “Our Birthday,” rew, 1 May 1902, 2.

106. In 1903, Moffatt would become city editor and then editor-in-chief of the Nelson Daily News. When his editorship ended, he returned to practising law in Nelson and died there of a stroke in 1928. In 1905, William K. Esling, long-time editor of the weekly Trail News and later a Conservative member of Parliament, bought the Miner and quickly toned down the paper’s anti-union rhetoric, adopting a “more conciliatory tone.” See Rosa Jordan and Derek Choukalos, Rossland: The First 100 Years (Rossland, BC: Harry Lefevre and the Rossland Historical Museum Association, 1995), 59.

107. The World, ultimately, was lost in the strike. As mentioned earlier, the Centre Star Mining Company launched a damage suit connected with the strike, and after a two-week trial, a Nelson judge decided against the union, fining it $12,500. The miners’ union hall and its assets were seized as part of the settlement. As Boucher notes, “Fortunately, the union’s lawyer, accurately predicting which way the verdict would go, had earlier advised the union to divest itself of all of its other assets, including its printing press and the Evening World.” Thanks to that sound legal advice, the World would survive for another two years, but the fight had been lost. See Victoria Daily Times, 18 July 1904; Boucher, “1901 Rossland Miners’ Strike,” 80.

108. See John Adcock, “Kootenay Newspaper Pioneer – ‘Colonel’ R. T. Lowery,” Yesterday’s Papers (blog), 7 January 2016, http://john-adcock.blogspot.com/2016/01/kootenay-newspaper-pioneer-colonel-rt.html; Michael Earle, “The ‘People’s Daily Paper’: The Glace Bay Gazette under ummwu Ownership,” Journal of the Nova Scotia Historical Society 7 (2004).

How to cite:

Ron Verzuh, “A Crusading Voice for the Mining West: How the Rossland Evening World Served Militant Workers at the Turn of the 20th Century,” Labour/Le Travail 92 (Fall 2023): 229–258, https://doi.org/10.52975/llt.2023v92.009.

Copyright © 2023 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2023.