Labour / Le Travail

Issue 93 (2024)

Obituary / Nécrologie

Remembering Natalie Zemon Davis

Joshua Brown, Radical History Review 24 (Fall 1980)

In the 1960s, Natalie Zemon Davis joined with her good friend Jill Ker Conway to bring feminism to History at the University of Toronto. Their presence, in a department that had never welcomed female faculty and barred female students from its History Club until 1968, was inspirational, even as women and workers remained rare candidates for recognition. As an undergraduate (1966–70) and doctoral student (1971–75) preoccupied with Canada, I had no female professors before I encountered Jill in a graduate course in American history and Natalie and Jill as the creators of Toronto’s first course in women’s history. While I benefited from the department’s leadership in the burgeoning field of Canadian studies, the brilliance and generosity of these outsiders shaped my own research and writing on women and workers. They changed my life.

As a teaching assistant (1971–72) in History 348 – women in Europe and North America from the 12th to the 20th centuries – I found a lifeline of friends and inspiration. Natalie’s ebullience and broad scholarship, warmly allied with Jill’s calmer persona, lit up lectures and audiences to chart links between past and present and to question patriarchy and capitalism. In the context of contemporary protest movements, from women to workers, Indigenous peoples, and Québécois, the result was heady. That her accomplishments matter-of-factly flourished in the midst of a lively household of children made her inspiration all the sweeter.

Natalie’s spirited insistence on the significance of women’s labour and resistance, whether as witches, weavers, writers, mothers, or queens, signalled the promise of the New Social History. Conversations and parties brought serious debate but also laughter and comfort. While my adviser mused that my thesis (1975) would probably be sufficient in incorporating women into the national story, Natalie’s recovery of New France founder Marie de l’Incarnation for History 348 – like her subsequent book, Women on the Margins (1985) – inserted Canada into a global story of women and work, both paid and unpaid. Even after she went forth to shake up UC Berkeley (1971) and Princeton (1978), her enchantment flowed on, recognized in the next century by the University of Toronto’s conferral of the honorific “professor emerita.” More important was her enduring impact in the Canadian Committee for Women’s History/le Comité canadien de l’histoire des femmes (now the Canadian Committee on Women’s and Gender History/le Comité de l’histoire des femmes et du genre, respectively) from 1975, the Canadian Committee on Labour History/le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du Travail from 1973, and Labour/Le Travail (revealingly revised from its original title, Labour/Le Travailleur [l/lt], in 1984), where champions of women’s and labour history of both Canada and elsewhere continued the shared sympathies she had embodied. It is no surprise that the three of us writing here – myself, Linda Kealey, and Mary Lynn Stewart – all took heart from such initiatives.

Today, more than 50 years after I met Natalie, I know that my doctoral thesis, published as The Parliament of Women: The National Council of Women of Canada, 1893–1929 (1976), and later contributions such as The New Day Recalled: Lives of Girls and Women in English Canada, 1919–1939 (1988), Losing Ground: The Effects of Government Cut-Backs on Women in BC, 2000–2005; Report for the BC Federation of Labour (2005) (with Gillian Creese), my directorship of the editorial board for l/lt (1983–86), and A Liberal-Labour Lady: The Times and Life of Mary Ellen Spear Smith (2022) owe much to a tiny enchantress who found a northern home after she and her husband, Chandler (himself another generous mentor), defied the US House Committee on Un-American Activities in the 1950s. In 2023, Natalie Zemon Davis left life’s stage, but her magic continues. I miss her.

* * *

My memories of Natalie focus on the woman who was not only a feisty, imaginative, and feminist historian but also a person who encouraged others to develop their talents. She was supportive of students, especially, but not only, of women. In a mostly male historical profession, she was keenly aware of the barriers to recognition and success. Her own experience at the University of Toronto (which failed to offer her a full professorship) underlined these obstacles, resulting in a move to Berkeley and later Princeton. Her feminist principles included concern for women, students, and workers. Natalie and her late mathematician husband, Chandler, raised three children in the midst of their academic careers, so she was well aware of the balancing act required especially for women. As Jill Ker Conway’s True North (1994) recalls, Natalie intervened in a daycare occupation at the University of Toronto in March 1970 that pushed the university to provide child care for its students and staff. The occupation of an administration building aroused male ire in the Department of History. A threatened vote to censure Natalie was avoided by skilful campaigning among department members and reminders of the role of debate in university education. No doubt the threat of the potential bad press of evicting babies, toddlers, and their parents helped. Jill and Natalie helped find a solution that ended the occupation peacefully.

Jill and Natalie also worked together at the University of Toronto to create one of the first courses in women’s history in 1970, recalled here by Veronica Strong-Boag. Later, a group of women’s historians at the University of New Brunswick, where I taught, submitted a nomination for a joint honorary degree to recognize their collaboration, and in 2005 it came to fruition. It was a joyous occasion, with both of them staying at our house while here for the ceremony. My last face-to-face interaction with Natalie occurred in 2014, when the International Federation for Research in Women’s History met for the first time in Canada. Natalie hosted a social event at her house in Toronto during the conference with many well-known women’s and gender historians present. In typical Natalie fashion, when she learned that I was pained by bursitis in my hip, she, then 86 years of age, proceeded to take me upstairs to her study to demonstrate the exercises she used to deal with the condition. I used them for many years after.

Even as the news of her death circulated, a new issue of the New York Review of Books arrived with an article by Susan Neiman, “Historical Reckoning Gone Haywire” (19 October 2023), on Germany and historical memory. In her discussion of German responses to anti-Semitism, Neiman notes a dispute over the performance of a play that features a love story between an Arab and a Jew. Labelled as anti-Semitic, the play was written by Lebanese Canadian Wajdi Mouawad, in consultation with Natalie Zemon Davis. Despite the fact that the play had been performed to great acclaim for several years prior in German cities as well as in France, Canada, and Israel, the debate raged on and the play was cancelled. Given Natalie’s sensitive explorations into the complicated relations among Christians, Jews, and Muslims in her later historical writings, the debate and attacks on her must have caused some pain for someone who sought to create links and understanding among these traditions.

* * *

Unlike Nikki and Linda, I did not have much contact with Natalie. Our few interactions impressed me with her intellect, generosity, and graciousness. As a graduate student, I saw her at the plenary session of the 1973 annual conference of the Society for French Historical Studies, where a distinguished (male) historian spoke. She asked the most perceptive and possibly disarming question of the speaker in such a constructive manner that it initiated a lively discussion not only between her and the speaker but also between him and other members of the audience. This, I learned later, was a rare occurrence in these sessions. As one of very few young women attending that conference, I was reinforced in my hope that women could someday play an equal role in the SFHS, and I was motivated to be similarly constructive in any interventions I might make at conferences, in reviews of colleagues’ scholarship, and in future comments on students’ papers and exams. I was not alone in that reaction. My only significant meeting with Natalie was when I asked her to be a speaker at our departmental series of invited speakers. Her talk was outstanding, but I expected that. I was more struck by her interaction with my colleagues, in which she expressed interest in their work and engaged in thoughtful conversations about history with some of them. She could be quite the enchantress.

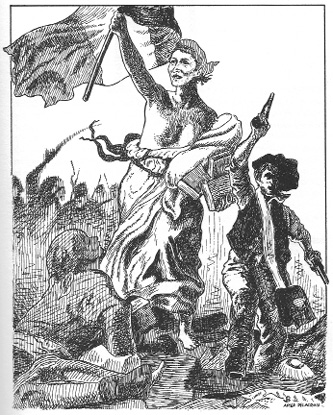

Intellectually, Natalie’s early essays and collections on peasants, artisan workers, and women in early modern France (specifically, Society and Culture in Early Modern France [1975], “Women in the Crafts” [1982], and “Women on Top” [1978]) profoundly influenced my cohort of French working-class and women’s (and later gender) historians. First and foremost, we adopted her perspective that workers in general, and working-class women in particular, were not passive and completely subjected. Rather, they had some agency and options, such as to riot, strike, and, in the case of women, take leadership roles, however restricted the roles might be. Moreover, she did not treat these activities in the traditional manner as ways of letting off steam that merely reinforced the hierarchical patriarchal order. Instead, she posited that they sanctioned political disobedience for both sexes and sex reversal events in particular expanded women’s behavioural possibilities. These events were moments when workers and women played an active role in making their history.

Ultimately, the most valuable part of her scholarly oeuvre has been her imaginative interdisciplinary methodology. In addition to her deft use of interpretive anthropology as practised by Clifford Geertz to understand people often dismissed as inarticulate, she used it to challenge dual spheres theory and other universalisms about women. Similarly, she employed literary structuralism as espoused by Mikhail Bakhtin to understand not only charivaris but other manifestations of popular discontent as a source of liberation. Finally, although she wrote about gender very early, she was cautious about how poststructuralists defined the term in the 1980s, warning about the dangers of any resort to universal statements about women or men.

I will miss her enlightening essays and books, her constructive commentary on other scholars’ work, and her cordiality toward all.

How to cite:

Veronica Strong-Boag, Linda Kealey, and Mary Lynn Stewart, “Remembering Natalie Zemon Davis,” Labour/Le Travail 93 (Spring 2024): 17–21, https://doi.org/10.52975/llt.2024v93.003.

Copyright © 2024 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2024.