Labour / Le Travail

Issue 93 (2024)

Research Note / Note de recherche

Multiscalar Toxicities: Counter-Mapping Worker’s Health in the Nail Salon

Abstract: This article analyzes nail technicians’ occupational health experiences using body and hazard mapping – a visual, low-cost, and worker-centred approach. Thirty-seven Toronto-based nail technicians from predominantly Vietnamese, Chinese, and Korean communities identified various occupational illnesses, injuries, and symptoms on visual representations of human bodies (body mapping) and linked these to their hazard sources in the nail salon (hazard mapping). The impacts identified include musculoskeletal aches and pains, stress and mental health concerns, various symptoms linked to chemical exposure, and concerns about cancer and reproductive health. Rather than a conventional occupational health approach, this work draws on Vanessa Agard-Jones’ expansion of the “body burden” as more than the bioaccumulation of chemical agents. As such, this article asserts that nail technicians’ body burden encompasses various types of occupational illnesses and injuries. In addition, nail technicians are exposed to broader “toxic” systemic inequities and structural conditions that allow these workplace exposures to occur and persist. By illustrating the embodied and experiential knowledges of nail technicians and contextualizing this lived experience, the body and hazard maps illuminate vast layers of harm – or multiscalar toxicities – borne by nail technicians. Moreover, as a group-based method, body and hazard mapping allow collective reflection and can spur worker mobilization toward safer and fairer nail salons.

Keywords: body mapping, hazard mapping, nail salon, multiscalar toxicities, occupational health

Résumé : Cet article analyse les expériences de santé au travail des prothésistes des ongles à l’aide d’une cartographie du corps et des risques – une approche visuelle, peu coûteuse et centrée sur le travailleurs/euses. Trente-sept prothésistes des ongles basés à Toronto, issus principalement de communautés vietnamiennes, chinoises et coréennes, ont identifié diverses maladies, blessures et symptômes professionnels sur des représentations visuelles de corps humains (cartographie corporelle) et les ont reliés à leurs sources de danger dans le salon de manucure (cartographie des risques). Les impacts identifiés comprennent les douleurs musculo-squelettiques, le stress et les problèmes de santé mentale, divers symptômes liés à l’exposition à des produits chimiques et les préoccupations concernant le cancer et la santé reproductive. Plutôt qu’une approche conventionnelle de santé au travail, ce travail s’appuie sur l’expansion de Vanessa Agard-Jones de la « charge corporelle » comme allant au-delà de la bioaccumulation d’agents chimiques. Ainsi, cet article affirme que la charge corporelle des prothésistes des ongles englobe divers types de maladies et de blessures professionnelles. De plus, les prothésistes des ongles sont exposés à des inégalités systémiques « toxiques » plus larges et à des conditions structurelles qui permettent à ces expositions sur le lieu de travail de se produire et de persister. En illustrant les connaissances incarnées et expérientielles des prothésistes des ongles et en contextualisant cette expérience vécue, les cartes du corps et des risques mettent en lumière de vastes couches de dommages – ou de toxicités multiscalaires – supportées par les prothésistes des ongles. De plus, en tant que méthode de groupe, la cartographie du corps et des risques permet une réflexion collective et peut stimuler la mobilisation des travailleurs vers des salons de manucure plus sûrs et plus équitables.

Mots clefs : cartographie corporelle, cartographie des risques, salon de manucure, toxicités multiniveaux, santé du travail

Nobody wants to come to Canada to accept this, being exploited in nail salons. Pregnant, thinking you have to leave this job.

—Jackie Liang, Nail Technicians’ Network

In 2013, staff at Toronto’s Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre (Parkdale Queen West chc) noticed a troubling trend: nail technicians were presenting to the centre with respiratory and dermatological health concerns. These initial observations led to the founding of the Healthy Nail Salon Coalition and, later, the worker-focused Nail Technicians’ Network, both of which advocate for safer working conditions in Ontario-based nail salons. Parkdale Queen West chc’s advocacy efforts mirror those in other jurisdictions. In California, Asian Health Services (ahs) staff established the Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative in 2005 after observing that nail technicians had similar health concerns – asthma, skin rashes, and reproductive health problems.1 In 2007, the Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative co-founded the US-based National Healthy Nail Salon Alliance in partnership with the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum (napawf) and Women’s Voices for the Earth. Like ahs, napawf was drawn to the issue “after receiving phone calls from distraught workers who experienced spontaneous miscarriages and had trouble conceiving.”2

After Parkdale Queen West chc’s initial observation, staff held a focus group with nail technicians. The focus group was done in partnership with the National Network on Environments and Women’s Health (nnewh).3 nnewh had worked on automotive workers’ heightened risk of breast cancer and understood the dearth of literature on women’s occupational health.4 Titled “How training and employment conditions impact on Toronto nail technicians’ ability to protect themselves at work,” the focus group was the first inquiry into nail technicians’ health in Ontario. Focus group participants disclosed “skin problems and irritations, allergies, upset stomachs, problems sleeping, tiredness, musculoskeletal issues, burning eyes and coughing.”5 Participants also shared their reproductive health concerns, which they linked to their occupational exposure to chemical toxicants in nail products.6

Parkdale Queen West chc soon developed the Nail Salon Workers’ Project, which advocates for nail technicians’ health via occupational health training, policy interventions, outreach activities, and other methods. To date, peer health educators have delivered more than 200 accessible and language-appropriate nail salon–focused workshops on respiratory health, ergonomics, reproductive health, and dermatological health. These workshops have increased worker awareness of occupational health and resulted in heightened use of personal protective equipment (ppe).7 Parkdale Queen West chc also houses the Healthy Nail Salon Coalition (hnsc) and the Nail Technicians’ Network (ntn). The latter, first imagined in 2014 as a nail technician–led association, was officially established in 2017. ntn is a worker-focused association that supports nail technicians in Ontario. Its activities include nail care skills development, labour rights training, English-for-the-workplace conversation circles, social events, and mutual aid initiatives. hnsc was established in 2015 and includes ntn as well as representatives in environmental, occupational, and public health.8 At its inception, the central aim was to “protect the overall health of nail salon workers by decreasing the risk of exposure to harmful toxic chemicals.”9 Since that time, the coalition has expanded its focus to include ergonomic considerations and labour rights. hnsc develops training and outreach materials, leads research, and advocates for policy-level interventions to ensure safer nail salons.

Building on the vital yet understudied topic of nail technicians’ occupational health in Canada, this article aims to show that nail technicians experience multiple types and layers of “toxicity.” This includes (1) chemical, musculoskeletal, and psychosocial hazards in the workplace; (2) systemic barriers in the labour market that funnel racialized im/migrant women into precarious and unsafe environments; and (3) structural violences that perpetuate the devaluation and abuse of Asian (broadly) workers and communities.

To understand nail technicians’ occupational health experiences, the body- and hazard-mapping method was utilized. In body maps, workers identify and attach occupational health harms to visual representations of human bodies. In hazard maps, workers identify occupational hazards on a visual representation of the layout of the worksite.10 Canadian occupational health scholar Margaret Keith describes this practice as “a visual data gathering and reporting technique as well as a tool for developing collective analyses and action plans.”11 The method allows workers to share and reflect on their occupational health experiences and concerns in a group-based environment. In collaboration with ntn and hnsc, 37 Toronto-based nail technicians identified the immediate sources of occupational harm in their work environments (hazard mapping) and linked these to their bodily health implications (body mapping). Notably, body and hazard maps are forms of counter-mapping, centring workers’ perspectives on their work and health.

Building upon the aftorementioned body- and workplace-level scale, this work contextualizes nail technicians’ occupational health experiences in broader systems and structures that are harmful to racialized im/migrant women workers. Rather than a conventional occupational health–rooted analysis, then, this article draws on scholarship at the intersections of environmental justice, labour studies, and science and technology studies – all of which demand that we situate material harm in broader infrastructural, structural, and historical conditions. Thus, drawing on and inspired by Vanessa Agard-Jones’ expansion of the term “body burden,”12 it is argued that nail technicians are exposed to multiple forms of “toxicity” in the workplace, from verbal abuses to musculoskeletal hazards and chemical exposures. However, these micro-forms of toxicity are rooted in broader “toxic” environments: exclusionary labour markets; discrimination at the intersections of gender, race, and migration status; and legacies of anti-Asian racism in the context of capitalism and colonialism. Multiscalar toxicities in the nail salon thus encompass various types of harmful exposures at three scales: the physical (workplace), the systemic, and the structural.13 Body and hazard maps tell us about more than embodied and workplace-situated harms; they show the material impacts of broader scales of violence.

Nail Salon Workers, Occupational Hazards, and the Regulatory Environment

Toronto is home to 1,306 licensed nail salons that are non-unionized small businesses or chains.14 These establishments offer a variety of nail and body care services. These include manicures, pedicures, shellac or gel semi-permanent polish application, acrylic nail application, and creative nail design – services that can additionally involve nail cleansing, trimming, and shaping, as well as hand, foot, and calf massage. Technicians may also perform hair removal services, eyelash extensions, and eyebrow tinting. A Toronto-based cross-sectional survey of 208 nail salons found that nail technicians most commonly perform manicures (99 per cent), pedicures (96 per cent), and shellac polish application (86 per cent). These are services that can involve awkward postures, prolonged sitting, and repetitive hand, wrist, and arm movements.15

In general, nail salons tend to be precarious worksites, defined by Leah F. Vosko as “involving limited social benefits and statutory entitlements, job insecurity, low wages, and risks of ill-health.”16 In 2013, the Ontario Ministry of Labour carried out its Vulnerable Workers workplace inspection blitz to ascertain compliance with the Employment Standards Act. In the category of salons, spas, and nail salons, the government inspected 92 establishments and issued a total of 195 compliance orders to 69 of them. It is unclear what the specific infractions were in nail salons; however, violations related to public holiday pay, vacation pay, overtime hours, and record-keeping were most common in all worksites inspected.17 Via outreach and research, Parkdale Queen West chc has found that nail technicians are often misclassified as independent contractors and receive commission-based renumeration – an arrangement that impedes their access to employment supports.18 Moreover, nail technicians across the sector tend to work long and nonstandard work hours (evenings and weekends) with few breaks.19

Various “pull” and “push” factors draw workers to the nail salon. In Toronto, nail technicians tend to be women of Chinese, Vietnamese, or Korean descent. A lesser percentage are from Tibetan, Latin American, and eastern European communities.20 Nail work is accessible. Kin and personal ties can foster employment opportunities in nail salons. In addition, Ontario-based nail technicians are not required to have formal licences or particular nail care training. Formal training requirements can be a barrier for newcomer workers, who may lack the finances and time to engage or re-engage in schooling. However, as ntn’s outreach work has shown, this has at times resulted in workers paying employers for in-salon apprenticeships.21 Several “push” factors also spur racialized im/migrant women’s entry to the sector and other precarious worksites, including language barriers, discrimination, lack of professional networks, difficulties accessing services, unrecognized credentials, lack of local work experience, social isolation, disproportionate household responsibilities, and lack of access to child care – all of which intersect to impede access to safe, fair, and well-compensated work.22 In turn, precarious work can lead to ill health: sleep disruptions due to nonstandard work hours, lack of rest due to long commutes, workplace injuries due to inadequate ppe provision and training, and stress due to disrespect and abuse in the workplace.23 Winnie Ng and colleagues refer to the precarious positioning of newcomer women in the Canadian labour market as fuelling a “public health crisis.”24 Further, Ontario-based studies show that these adverse occupational health experiences are coupled with a reluctance to voice concerns owing to fears of reprisal, beliefs that concerns will not be heeded, and worries about relationship damage.25 The latter is a pertinent concern for newcomer workers who may depend on kinship ties for their livelihoods.

Nail technicians are, in addition, exposed to various chemical toxicants in nail products, some of which have been detected at heightened levels in workers’ bodies and in nail salon environments. These include phthalates26 and volatile organic compounds (vocs)27 – both of which are linked to adverse health outcomes. In a study of six Colorado-based nail salons, Aaron Lamplugh and colleagues detected benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (btex) at levels comparable with those in oil refineries.28 Moreover, a Toronto-based study of eighteen nail salons detected certain flame-retardant chemicals at levels exceeding those found in e-waste facilities.29 Common chemical toxicants in nail products have been linked to a host of occupational health harms, including at low levels of exposure.30 This includes skin irritations, respiratory problems, and eye sensitivities.31 In addition, while nail salon–based evidence of reproductive harm is limited,32 the risk of cancer is unconfirmed,33 and there are no nail salon–based studies on hormone disruption, studies have linked common chemicals in nail products to reproductive, intergenerational, endocrine, and cancer-related health impacts. These exposures occur in a context of limited access to occupational health information. The Ontario Ministry of Labour found that close to 75 per cent of 225 nail technicians surveyed were unaware of their occupational health and safety rights. Moreover, only 47 per cent of nail salon employers understood their duty to protect workers’ health.34

Regulatory challenges further impede worker protection. In Canada, nail salon licensing and public health adherence are regulated at the municipal level, while occupational health and employment standards are regulated at the provincial level; in addition, chemicals management is regulated at the federal level. As hnsc member Anne Rochon Ford writes, “Because of varying levels of responsibility for oversight, nail salons fall between the cracks, and their workers are its victims.”35 The challenge concerns both the regulatory scope and enforcement. On the former, Canadian toxics regulation is slow to align with newfound health information. To illustrate, dibutyl phthalate (dbp) – a chemical known as one-third of the “toxic trio” in nail products (alongside formaldehyde and toluene) – is allowed in cosmetics sold in Canada. In contrast, the European Union bans dbp in all cosmetics because of its status as a reproductive toxicant.36 On the issue of enforcement, while methyl methacrylate (mma) is banned in Canadian cosmetics, the substance continues to be detected in nail salon environments and in nail products.37 These regulatory gaps and oversights interfere with nail technicians’ health.

Expanding the Body Burden

This work situates the body-mapping method within Agard-Jones’ expansion and reframing of the “body burden.” Agard-Jones states,

[The body burden is] a toxicological term … The idea is that this is how we measure accumulated amount of harm … [H]arm has conventionally been measured by material [chemical] substances, like mercury, like lead, like ddt, like chlordecone, but these emergent conversations about how, for example, stress … might cause enduring harm or emergent conversations about the social determinants of health … Those kinds of questions … could productively be integrated into a concept of body burden, so … not just the things we can document in our blood, urine … [H]ow else might we think [of] these burdens?38

This broadened definition further encompasses the historical and structural context: how bodies bear (and resist) oppression. Reflecting and drawing on Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s foundational scholarship, Agard-Jones prompts us to “scale inwards, recognizing the multiple levels at which our material entanglements – be they cellular, chemical, or commercial – might be connected to global politics.”39 Bodies are thus embedded in a broader set of relations, material and otherwise. Redefined, the body burden involves the bodily accumulation of various types of harms that result from exploitative, oppressive, and otherwise harmful systemic and structural conditions.40 This approach is distinct from toxicological definitions, which reduce the body burden to chemical toxicants – a molecular-level hyperfocus that can obscure the broader context of exposure.41

Inspired by Agard-Jones’ groundbreaking work, “toxicity” in the context of this article comprises more than chemical toxicants. Different types of hazards cross into nail technicians’ bodies, from musculoskeletal aches and pains to verbal abuses and exposure to chemical agents. These harms are rooted in broader systemic and structural violences – meso- and macro-scales of toxicity. In the nail salon, the intertwining raced, classed, and gendered facets of capitalist super-exploitation funnel racialized im/migrant women workers into undercompensated, underrespected, and unsafe work, while legacies of anti-Asian racism perpetuate their abuse and devaluation. These layers denote multiple scales of “toxicity” that are borne in/on workers’ bodies.

Counter-Mapping Workers’ Health

In contrast to “top-down” notions of health expertise, body and hazard maps are snapshots of the workplace that are based on worker perspectives – their embodied and experiential knowledges. Margaret M. Keith and James T. Brophy write that “mapping involves the direct input of those who are most intimately familiar with their workplace … When created collectively, hazard mapping has an intrinsic validity check … that includes not only the input, but also the scrutiny of the co-participants.”42 The method is worker-driven, low-cost, accessible (in language and format), and collaborative and can affirm workers’ experiences of ill health.43 It can highlight the material impacts of labour exploitation in addition to conventional occupational health hazards. Further, body and hazard mapping can facilitate sharing and collective reflection, which are essential in non-unionized and disconnected workplaces, such as nail salons. The method thus has the potential to prompt solidarity and action toward fairer, safer, and healthier work environments.44

In Ontario, body and hazard mapping have been conducted in various workplace contexts, including with gaming workers, foundry and insulation workers, and long-term care staff. Via body maps, gaming workers identified repetitive strain injuries, musculoskeletal pain, tinnitus, and various other adverse health outcomes linked to inadequate ergonomic design, noisy work environments, poor indoor air quality, and other occupational hazards.45 Foundry and insulation workers identified respiratory disease, various cancers, hearing loss, and renal disease linked to asbestos exposure.46 In addition, long-term care staff identified physical, verbal, and sexual violence by residents – a phenomenon rooted in broader conditions of staff undervaluation.47

While there are variations in body-mapping practice that have distinct legacies, the present form of body and hazard mapping is traced to the Italian workers’ model in the 1960s. The Italian workers’ model incorporated questionnaires and risk maps, where workers collectively identified workplace hazards and their health implications.48 The model grew from workers’ demands to be involved in workplace risk identification. This development coincided with the rise of participatory action research (par) in the Global South, which emphasizes community-based knowledge and expertise.

Body and hazard mapping respond to the need for worker-driven approaches that can stand alone or supplement top-down interventions that construct workers bodies as “research subjects,” such as in biomonitoring and toxicology.49 While important, such investigator-led interventions are often framed as more “objective” science, devoid of experiential and embodied knowledges. This inadvertently results in the devaluation of workers’ lived experiences – a knowledge that may then be constructed as “suspicious” or even “fake” in contexts of occupational illness and injury.50 Liza Grandia uses the term “toxic gaslighting” to denote such dismissals in the context of chemical exposure, where lived and sensory experiences of toxicity are met with institutional doubt.51 This is relevant to women workers whose occupational health problems have been ignored in male-dominated fields and dismissed in woman-dominated fields, where work is falsely perceived as “easy,” “light,” or “natural.”52 Further, women workers have been subject to accusations of hysteria when sharing occupational health concerns.53

Body and hazard mapping have the potential to disrupt this knowledge hierarchy, facilitating epistemic justice. This method is a form of corporeal-level counter-mapping – a counternarrative that asserts embodied experiences of occupational harm and serves to challenge top-down, power-laden, and external constructions of workers’ bodies. Counter-mapping is a critical map-creation practice in Indigenous cartographies. The method visually counters colonial map-creation with Indigenous representations of land and space. Counter-mapping understands that map-making is a power-laden practice – one that can either erase and delegitimize or centre and value community-based knowledges.54 Counter-mapping positions workers and other harm-impacted communities as experts of their health and environments. It reflects Andrew Watterson’s conception of “lay epidemiology,” which advocates for worker-led and -driven interventions in occupational health, as well as Phil Brown’s “popular epidemiology,” which refers to the use of community-led data collection and mobilization.55 As Phil Brown and Edwin J. Mikkelsen write, “people often have access to data about themselves and their environment that are inaccessible to scientists … In fact, public knowledge of community toxic hazards in the last two decades has largely stemmed from the observations of ordinary people.”56 Thus, as a method of counter-mapping, body and hazard maps showcase workers’ reclamation of the stories of their bodies and workplaces.

While they are not drawn upon in this work, it is pertinent to note other vital forms of body mapping used in health research. Most notably, this includes in hiv/aids activism, where a distinct arts-based form of body mapping is used as a storytelling and art therapy tool. Participants visually and artistically map their pain, emotions, illness, strengths, visions of the future, and sources of support.57 While this method differs from workplace health–related methods, some labour-focused scholars have drawn inspiration from this latter body-mapping tradition. One example is provided by Denise Gastaldo and colleagues, who developed the “body-map storytelling” method to frame their work with undocumented workers in Ontario.58 Moreover, Ruth Marie Wilson and colleagues use the method of “World to Body Mapping” in their work with precariously employed racialized workers in Toronto’s Black Creek community.59 Health researchers use body-map storytelling and other, similar body-mapping techniques in various contexts, including – but not limited to – gendered violence, sexual health promotion, and mental health.60

Body and Hazard Mapping with Nail Technicians

In 2018, hnsc members identified five primary aims to guide their advocacy efforts: (1) capacity-building, to increase nail technicians’ leadership in advocacy work; (2) engagement with salon owners, to facilitate improved workplace health conditions; (3) regulatory interventions, such as improved toxics management; (4) a focus on growing public awareness; and (5) academic research with nail technicians, to better inform advocacy efforts and interventions. Consistent with the final aim, this study was initiated to better understand nail technicians’ perspectives on their exposure to workplace hazards and the resultant health outcomes. The aims and questions were formulated in consultation with members of ntn and hnsc. The partners further advised on and secured accessible space to conduct the in-person body- and hazard-mapping workshops.

Three two-hour workshops were held between August 2019 and February 2020. Participants were sought by ntn, which conducts outreach in nail salons across the Toronto region. Due to potential economic risks in the context of group-based data collection, participants were instructed not to name or discuss specifics that would tie them to their places of employment; therefore, some pertinent information was not collected. The 37 participants all identified as female and ranged in age from young adults to seniors. Participants had varying levels of expertise in nail care; some had years of experience as nail technicians, while others were relatively new to the sector. Apart from one person, all participants identified as being from Chinese, Vietnamese, and/or Korean communities. Based on data from Toronto Public Health inspections and outreach conducted by ntn, the workshop makeup reflected the general ethno-racial makeup of nail technicians in Toronto.61

Body mapping

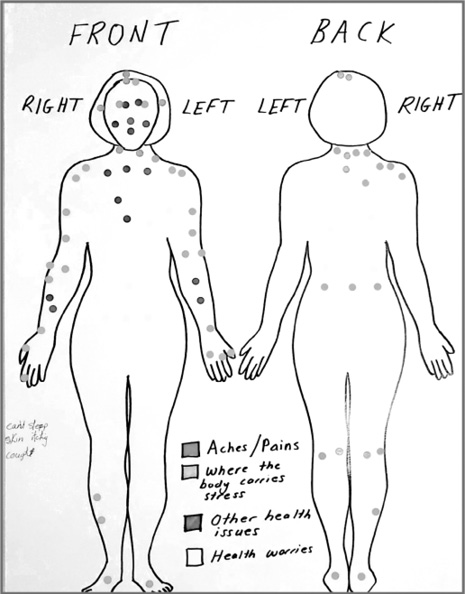

For body mapping, participants were divided into small groups of four to seven based on their first language. For the first and second workshops, each table included a member of ntn or hnsc, who provided translations for Chinese- and Vietnamese-speaking participants, facilitated discussion, and answered questions to support participants in their completion of the body maps. The third workshop was co-facilitated in Korean by a member of hnsc. Where possible, participants were further divided by nail salon experience level, with more experienced participants in one group and less experienced participants in another. Each small group was given a blank body map with a generalized representation of the front and back of a human figure. Participants were instructed to discuss and collectively identify their occupational health–related experiences and concerns on the body maps. To indicate these harms, circular stickers were provided: (1) red stickers represented muscular aches and pains, (2) green stickers represented stress-induced harms, (3) blue stickers represented all other illnesses, injuries, and symptoms, and (4) yellow stickers represented health worries. Several groups additionally included keywords on their body maps to ensure that the maps fully captured their health experiences (see Figure 1). While nail technicians may perform a variety of tasks in the nail salon, such as waxing or cleaning, the participants’ responses were limited to their nail care duties.

Following the body-mapping exercise, we reconvened as a large group. Each small group identified the specific health harms and concerns indicated on their body map. These were recorded on colour-coded notes that corresponded to the type of health harm or concern identified: muscular aches and pains (pink), stress-induced harms (green), other health harms (blue), and health concerns (yellow). Members of hnsc assisted in recording the health harms identified, allowing the author to facilitate discussion and other members of the coalition and ntn to translate. The colour-coded notes were then used to facilitate hazard mapping.

Hazard mapping

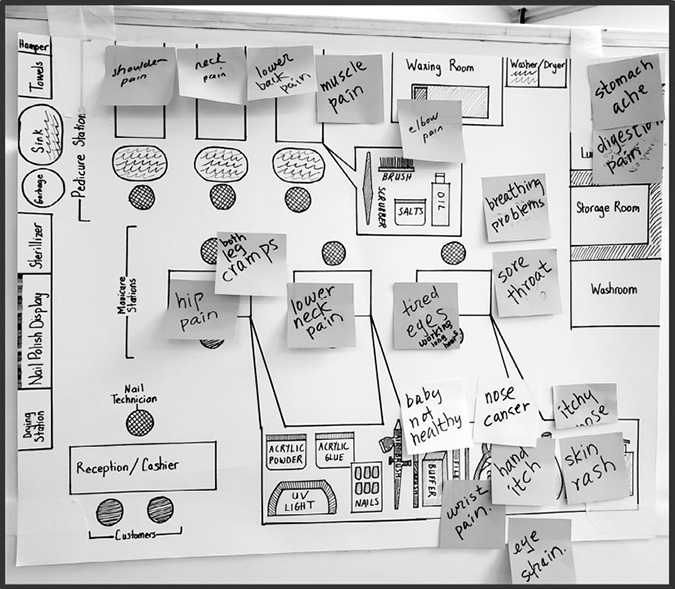

A nail salon mock-up illustration was presented to participants. While hazard maps generally require workers to draw their work environments, this was not possible in the time allotted. Further, participants were from various worksites with differing layouts. To ensure accuracy, participants were asked to supplement or correct any errors on the nail salon mock-up. To populate the hazard map, we collectively reviewed each health harm or concern written on the colour-coded notes. Questions such as “What causes skin rashes at work?” and “What makes you worried about your reproductive health at work?” were asked to prompt reflection and discussion. Once a group consensus was reached, the relevant health harm was placed on its source illustrated on the nail salon mock-up (see Figure 2).62

Findings: Mapping Hazards and Harms in Nail Salons

Figures 1 and 2 were created by nail technician participants in the first workshop.63 In total, the workshops produced seven body maps and three hazard maps, all of which identified similar health harms, concerns, and hazard sources. The maps showcase a lack of attention to workers’ comfort in furniture and equipment design, exposure to chemical toxicants, exposure to verbal abuses, the conditions of precarious work, and the material impacts therein. The maps were co-created and analyzed primarily with participants during the workshops – a noted benefit of body and hazard mapping. Afterwards, additional analysis was undertaken to understand common themes and identify notable topics across the various body and hazard maps created. Table 1 is a summary of the illnesses, injuries, symptoms, concerns, and associated hazard sources identified during the workshops.

Table 1: Occupational Health Experiences, Worries, and Hazard Sources in Nail Salons

|

Body system |

Health experiencesa and/or worriesb identified by nail technicians |

Source of hazard according to nail technicians (type of hazard) |

|

Neurological |

Headachea Migrainea Difficulty sleepinga Tinnitusa Depressiona Mood swingsa Mental health concernsb |

Stress-related (psychosocial) Work pressure (psychosocial) |

|

Dizzinessa |

Nail products (chemical) |

|

|

Respiratory |

Breathing problemsa,b Stuffy nosea Itchy nosea Nosebleedsa Throat infections, sorenessa Cougha |

Nail products, including acrylic dust (chemical) |

|

Pressure in chesta Throat paina Cougha |

Stress-related (psychosocial) |

|

|

Digestive |

Digestive problemsa Sore stomacha |

Stress-related (psychosocial) Work pressure (psychosocial) |

|

Stomach achea Digestive paina Acid refluxa |

Work pressure – no lunch or unable to eat on time (psychosocial) |

|

|

Ocular |

Itchy eyesa Eye sensitivitya |

Nail products (chemical) |

|

Tired eyesa Blurry visiona |

Stress-related (psychosocial) Work pressure – working long hours (psychosocial) |

|

|

Eye paina Eye straina Dry eyesa |

Intense concentration (ergonomic) |

|

|

Dermal |

Itchy skina Skin allergiesa Rasha Dry skina Sensitive skina Blistersa |

Nail products (chemical) |

|

Fungusb |

Customers (biological) |

|

|

Itchy skina |

Stress-related (psychosocial) |

|

|

Musculoskeletal |

General muscle aches and painsa Neck achea Shoulder achea Upper, mid, lower back achea Hip achea Arm and elbow achea Wrist achea Hand achea Pain between thumb and index fingera Numbness in the legsa Leg crampsa Knee achea Foot achea |

Manicure and pedicure stations (ergonomic) |

|

Neck achea Lower back achea Numbness in the toesa |

Stress-related (psychosocial) |

|

|

Numbness in the armsa Numbness in the handsa |

Nail products (chemical) |

|

|

Wrist aches and painsa Finger aches and painsa |

Tools (ergonomic) |

|

|

Reproductive Health |

Inability to have healthy childrenb Miscarriageb |

Nail products (chemical) |

|

Increased menstrual paina |

Stress-related (psychosocial) |

|

|

Endocrine |

Hormone disruptionb |

Nail products (chemical) |

|

Cancer |

Cancerb |

Nail products (chemical) |

aRefers to health experiences.

bRefers to health worries.

Muscle aches and pains

Muscular aches and pains were identified from head to toe, spanning the head, shoulders, neck, back, hips, arms, elbows, wrists, legs, knees, and feet. Most of these aches and pains were linked to the manicure and pedicure stations, as the provision of nail care services can entail awkward postures and positions. Nail technician participants identified neck and lower back ache as also being stress-induced, demonstrating the bodily implications of psychosocial hazards. Sadaf Sanaat, D. Linn Holness, and Victoria H. Arrandale found a similar impact; in surveys with 155 Toronto-based nail technicians, the most commonly reported symptoms were neck (44 per cent) and back pain (38 per cent).64 In addition, participants in the workshops linked wrist, hand, and finger pain to the use of nail care tools.

Figure 1. Body map (Nail Salon). Created by “Healthy Workplaces, Healthy Bodies” workshop participants.

These findings occur in a broader context of erasure in which a lack of research and reporting and, as a result, limited representation in workers’ compensation claims combine to erase women’s occupational experiences of musculoskeletal injury.65 This is in addition to the broader conditions of sexism that underlie the labour market, particularly the dismissal of women’s experiential health knowledges at work and the feminization of precarious work.66 Experiences of musculoskeletal injury may be pronounced for racialized newcomer women, as processes of de-skilling and funnelling into precarious work may expose them to a greater risk of injury or illness.67

Figure 2. Hazard map (Nail Salon). Created by “Healthy Workplaces, Healthy Bodies” workshop participants.

Stress

Participants linked stress to many of their adverse health experiences – headaches, difficulty sleeping, moodiness, muscular aches and pains, pressure in the chest, digestive problems, tired eyes, itchy skin, and increased menstrual pain. When asked about the sources of stress, participants shared their work demands, which include pressure to serve multiple clients in quick succession and scheduling complaints, such as irregular hours, long hours, missed lunch breaks, and slow periods. In addition, participants expressed dissatisfaction with their income – low wages, inadequate tips, and the late payment of wages. The pressure to serve multiple clients is linked to nail technicians’ pay structure. Many are misclassified as independent contractors and receive a commission from each client’s nail care fee instead of an hourly wage or salary. This creates pressure to see as many clients as possible and disadvantages less experienced nail technicians who may be slower or lack a client base.68 In addition, some participants identified their nonstandard hours as an impediment to their access to family time. This is consistent with Stephanie Premji’s research, which found that some immigrant workers must reduce their time with family because of their work hours. Premji noted that this situation induced feelings of guilt in some immigrant mothers (as per gendered expectations of care work).69

Some workplace interactions were an additional source of stress, as participants were forced to deal with rude behaviours and verbal abuses – particularly from clients. Rude clients were a focal point in the workshops – perhaps because in a large group setting among unfamiliar faces, clients are a safer topic of discussion than bosses. Indeed, a limitation of this work is that owing to potential economic risks, participants may have been reluctant to “out” their bosses. Participants shared that clients often dismiss their skill sets and waste time with indecisiveness – an understandable frustration for workers amid the pressure to serve multiple clients quickly. One young nail technician further commented that clients treat them “like trash,” indicating a sense of disposability. This comment evokes Mark Stein’s conception of the “polluting” or “poisoning” impact of client-worker relations, where verbal abuses are experienced as a type of “toxic” exposure. In Stein’s review, front-line workers describe abusive clients as “obnoxious [emphasis added]” and “venomous,” indicating a process of poisoning. Further, Stein writes that workers are likened to waste dumps in that they are “given shit” and forced to put up with “garbage” from customers70 These abuses can traverse the boundaries of the client-worker interaction. Workers carry the associated stress to their other interactions in the worksite and to their home environments.71

The stressors in nail technician–client interactions can be framed in Miliann Kang’s concept of “body labour,” “in which service workers attend to the physical comfort and appearance of the customers, through direct contact with the body (such as touching, massaging, and manicuring), and by attending to the feelings involved with these practices.”72 With body labour, Kang extends Arlie Russell Hochschild’s concept of “emotional labour” to account for the interrelations between the body and emotion-work in nail salon–based care labour.73 As in emotional labour (which refers to workers’ regulation of their emotions for customer comfort, particularly in woman-dominated sectors), nail technicians are expected to calm, appease, and attend to the client’s emotional needs via verbal and physical interactions – even at the expense of their own mental health.74 In a study by Ng and colleagues, a Toronto-based nail technician shared the contradictions between the expectations of body labour, the material conditions of work, and their actual feelings: “As a new nail salon worker, I was not treated fairly … You are under constant pressure to work faster, to chat and make customers happy! When it’s not busy, the boss will ask one of us to go home. No pay for the rest of the day. It’s so upsetting when work is so insecure [emphasis added].”75 Although they did not explicitly point to negative interactions with customers as a cause, workshop participants linked depression, mood swings, and concerns about their mental health to their work-related pressures. On one body map, participants wrote in capital letters, “bad mood.”

Chemical hazards

Participants further discussed their exposure to chemical toxicants – an additional source of stress. Nail technicians questioned the long-term impacts of their daily and cumulative exposures. Although some chemicals may be imperceptible, participants identified a host of illnesses and symptoms that they linked to chemicals in nail products. While acetone was named, participants generally used the broad language of “chemicals” to express their concern. The associated harms they identified include dizziness, itchy and sensitive eyes, and dry, itchy, and sensitive skin (including rashes and blisters). Respiratory health effects were also linked to exposure to chemical toxicants and acrylic nail dust (produced when acrylic nails are filed). These respiratory health effects included breathing problems, stuffy and itchy noses, sore throats, and cough.

Participants further expressed concern about cancers, hormone disruption, and reproductive and intergenerational health, all of which were linked to chemical exposures at work. Of the seven body maps created, six groups placed yellow stickers indicating health concerns on the reproductive system. Four of these six body maps featured a cluster of yellow stickers, indicating a particular severity of concern. One body map also included the clarifying term “baby.” The specific concerns that nail technicians identified were around miscarriages and the ability to have healthy children. While data in the nail salon context is limited, other occupational as well as animal studies on common chemical toxicants in nail products indicate potential reproductive, intergenerational, endocrine, and cancer-related effects.76

Multiscalar Toxicities

Nail technicians’ work experiences can be traced to the funnelling of racialized newcomer women into precarious labour, their exploitation, and their resultant disproportionate exposure to occupational hazards. In her foundational work, Roxana Ng writes, “The reality of the labour market is such that non-English speaking women, particularly those from visible minority groups, tend to be concentrated at the bottom rungs of most service and manufacturing sectors.”77 Grace-Edward Galabuzi extends this assessment, describing the intersections of race, class, and gender discrimination and their impact on racialized women in the Canadian labour market: “Racialized women … are excluded from secure, well-paid employment, and are often powerless to challenge the situation. Racism and sexism clearly interact with class to define the place of racialized women workers in the labour market, even in relation to other women workers.” 78 This produces a racialized-gendered division of labour, where racialized im/migrant women are funnelled into precarious, low-wage, and undervalued labour, including service, manufacturing, and care work.79 Winnie Ng and colleagues term this phenomenon the “precarity capture,” which then traps these women in a cycle of precarious work. The precarity capture is produced and intensified by precarious immigration status, language barriers, lack of Canadian work experience, and a lack of recognition of international credentials. In addition, disproportionate household and caregiving responsibilities, lack of access to child care, and the insecurity of temp agency work trap newcomer women in a cycle of simultaneous overwork and poverty. Ng and colleagues clarify that the precarity capture cannot be separated from its health impacts. Lack of access to sick days, breaks, and other workplace rights, in addition to a lack of voice, perpetuates illness and injury – or precarious health.80 This is pertinent to the nail technician participants, who shared various health impacts rooted in workplace pressures in the context of precarious work.

The labour market experiences of nail technicians are further influenced by the intersections of anti-Asian racism, gender discrimination, and xenophobia. Part of the issue is its naturalization – a long-standing issue for racialized workers, newcomer workers, and women, whose bodies are deemed “naturally suited” to various forms of precarious and unsafe work, such as care labour.81 In the nail salon, stereotypes of “nimble-fingered” workers plague and characterize East and Southeast Asian women as being in possession of a “natural” dexterity fit for intricate hand-work, like nail care.82 For instance, Tippi Hedren (the Hollywood actress) is often cited as spurring Vietnamese women’s entry to the nail care sector in California. Hedren facilitated training opportunities (manicuring, typing, and sewing) for Vietnamese refugees in the mid-1970s.83 Allegedly, Hedren was “impressed with the women’s hand dexterity.”84 Kang further discusses the Orientalist tropes embedded in some customer perceptions of Korean nail technicians, who – in the client’s gaze – are seen as more biologically or culturally suited to perform bodily care work. In Kang’s work, one customer states, “the quality of the massage is much better here … Culturally, there are things Asians can bring to [this] service that I don’t think others are sensitive to … This [American] culture doesn’t understand a service. It’s not subservience or being a doormat. It’s just the level to which you are willing to accommodate the needs of another, to go out of your way.”85 This comment evokes both a perceived biological ability to perform body work as well as a cultural stereotype of Asian (broadly) women as particularly skilled in servitude.86 Such racial-gender essentialist perceptions of “natural” ability undermine the association of nail care with skilled work. As Tania Das Gupta contends, “nimble fingers” are “taken as a genetic given for which [the worker] is not valued or paid.”87 The perception that nail care work stems from natural talent rather than developed skill contributes to the devaluation of nail technicians’ skill sets that partly fuels precarity in this sector.

Workplace illnesses and injuries are thus not separate from their context. Occupational hazards, barriers embedded in the labour market, and broader systems of exploitation produce material harms that are experienced by nail technicians – and visualized here via body mapping. Like Richard Lewontin and Richard Levins’ concept of the “proletarian lung”88 or Joan Benach and colleagues’ terming of the “capitalist liver”89 – both of which reference capitalism’s regulation of and subsequent harm unto workers bodies – it is likewise pertinent to refer to nail technicians’ body burdens as reflective of “capitalism’s skin” or even “gendered-racism’s back.”

Yet the health outcomes that result from unsafe work are often framed as the worker’s fault. For racialized newcomer workers, in particular, racialized discourses of hygiene may underlie their experiences of occupational health. These assume that workplace illness and injury are rooted in newcomer workers’ perceived “unhygienic” practice, poor health, lack of education, or general carelessness – all myths that blame the worker and not the conditions of work.90 Moreover, racialized im/migrant workers may be positioned as “other” – “out of place” and, by extension, “dangerous” and “unwelcome,” a type of “toxicity.” This narrative is reproduced in mainstream perceptions of the nail salon.91 Popular media depictions often characterize Asian-owned and -staffed nail salons as unhygienic spaces and nail technicians as spreaders of fungal infection – a perception that, in part, undergirds the disrespect and abuse that workers in the sector experience. To illustrate, in 2020, Larry Gaynor (ceo of major nail product and cosmetic supplier tng Worldwide) stated in a webinar, “if you’re in a nail business, the biggest enemy is the Vietnamese salon.” Gaynor claimed that Vietnamese-run salons have subpar hygiene and customer service practices. Moreover, Gaynor claimed that Vietnamese nail product brands are “toxic”92 These perceptions are rooted in the historical modes of anti-Asian racism in North America – from the classification of Vancouver’s Chinatown as more susceptible to cholera in 1890 to the labelling of Chinese women as sex workers and “disease carriers” in the 19th century.93 These labels are consistent with white settler-colonial aims, which cast Asian workers as a hyperexploitable labour force and an unwelcome and “contaminating” presence94 – narratives that are not far removed from how working-class newcomer Asian workers are treated and perceived today.

Most recently, the covid-19 pandemic illustrated these particular modes of anti-Asian racism in Canada, as primarily Chinese, as well as other East and Southeast Asian communities, were blamed for the pandemic and, as a result, subject to verbal and physical abuses.95 As Kang writes, “contemporary debates about Asian nail salons as hotbeds of disease and violators of US [and Canadian] labor and living standards propagate ‘new yellow peril’ stereotypes that are evocative of the anti-Asian sentiments that predominated more than a century ago.”96 In turn, anti-Asian racism spurs its own adverse physical and mental health implications – additional layers of the “toxic” body burden.97 In response to the rise in anti-Asian racism in the wake of the covid-19 pandemic, ntn and Parkdale Queen West chc partnered with the Chinese Canadian National Council, the Chinese and Southeast Asian Legal Clinic, and the Toronto Vietnamese Alliance Church to create the pocket guide Responding to Racism at Work: A Nail Technician’s Guide. The guide includes descriptions of overt and covert racism as well as strategies to employ when faced with racism or a bystander to a racist act.

Mapping toward Action and Justice-Seeking

Body and hazard mapping are more than methods to identify harms and their workplace roots. The method can collectivize otherwise individualized health experiences – a vital outcome in small, disconnected, and un-unionized businesses, like nail salons. Following one workshop, a participant commented, “I thought I was the only one.” This comment reflects their prior belief that their occupational health experiences were an individual rather than a sector-wide phenomenon. Such shared reflections and newfound learnings are fundamental to worker mobilization, prompting increased solidarities and action.98 In fact, worker participation in ntn’s events increased following the body- and hazard-mapping workshops.99 This indicates an increased level of engagement in nail salon advocacy work. Thus, while body maps may inadvertently (and incorrectly) present nail technicians as passive recipients of harm, the process in fact has the potential to mobilize workers. As Marco Armiero and Massimo De Angelis contend, “the embodiment of inequalities in the human body produces not only victims but also rebellious subjects who do not comply with the neoliberal narrative.”100

However, the covid-19 pandemic began just one month after the completion of the final workshop. This slowed participation. As concerns shifted to job losses, ntn shifted from addressing chemical, ergonomic, and labour rights–related occupational concerns to focusing on mutual aid and livelihood support. With such a major disruption, it is difficult to ascertain what the long-term impact of the workshops would have been on collective organizing in the nail salon sector.

While the covid-19 pandemic necessitated a shift in focus, the body- and hazard-mapping workshops provided a snapshot of nail technicians’ occupational health experiences and salon-based hazards – one that can inform and guide the focus and interventions of ntn and hnsc. Therefore, the benefit is twofold. As a counter-mapping method, body and hazard mapping, in facilitating worker voice and collectivization, is a mode of epistemic justice. Further, the knowledge gained can inform advocacy to prompt fairer and safer working environments. In sum, body and hazard mapping facilitated the recognition of shared grievances – grievances that could be mobilized into increased worker participation in nail salon advocacy.

Conclusion

As we frame occupational health as more than a matter of physical hazards at the worksite, new understandings emerge. The conditions that mark much of the nail salon sector are not solely a matter of “bad bosses,” though this is certainly a concern. Nail technicians are exposed to a vast array of workplace hazards that are rooted in systemic inequities in the labour market and structural violences, such as legacies of anti-Asian racism and xenophobia coupled with labour exploitation under capitalism and colonialism. The concept of multiscalar toxicities encompasses these vast layers of exposure – the workplace, the system, and the structure. In turn, these hazards produce an array of adverse bodily impacts, such as those illustrated and expressed by nail technician participants. Moreover, in addition to the immediate, systemic, and structural layers of “toxicity” are intergenerational layers. Nail technician participants consistently expressed a profound concern about their reproductive health and commented on the adverse impact of nonstandard work hours on their family time. Future research must attend to such intergenerational impacts that are associated with precarious work in the nail salon sector. The body and hazard maps presented and discussed are thus more than indications of workplace-rooted harm. When read more deeply and contextualized, they demonstrate the material impacts of vast layers of structural and infrastructural inequities embedded in what is Canada.

Moreover, the body and hazard maps are a mode of epistemic justice: workers from diverse communities, from various salons, and who had expressed having little voice/power (in relation to salon owners and customers)101 shared their work experiences and reflected together – a vital process considering the disconnection of workers in the many independently owned nail salons in Toronto. Worker voice and participation is fundamental to foster safer workplaces102 – a process that body and hazard mapping can invigorate. While the covid-19 pandemic impeded long-term mobilization, the maps did initially foster a sense of collectivity and drive to take action toward safer salons, as demonstrated by the increased participation in events held by ntn after the workshops. Therefore, body- and hazard-mapping methods can be useful in enabling a more unified workforce and, in turn, safer worksites.

I am indebted to the Nail Technicians’ Network, the Healthy Nail Salon Coalition, and the many nail technicians who generously shared their knowledges to create the body maps and hazard maps. In addition, I am grateful to occupational hygienist, ergonomist, researcher, educator, and body-mapping originator Dorothy Wigmore, who shared time and expertise to guide me on the process of body and hazard mapping. I am further thankful to Dr. Margaret Keith, who shared her brilliant dissertation on the method. Dr. Keith and Dr. James Brophy’s use of the method in various workplace contexts is a source of inspiration. This article is based on my dissertation, “Multiscalar Toxicities: Mapping Environmental Injustice in and beyond the Nail Salon.” Therefore, I am also thankful to the dissertation and examination committee, who shared their expertise and thought-provoking feedback: Dr. Dayna Nadine Scott, Dr. Deborah McGregor, Dr. Andil Gosine, Dr. Miliann Kang, Dr. Leah F. Vosko, and Dr. Sarah Flicker. Finally, thank you to the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback.

1. California Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative, Issues Affecting Nail Salon Workers, accessed 10 July 2022, https://www.cahealthynailsalons.org/.

2. Turner Willman, “Toxins in Nail Salons: When Environmental and Reproductive Justice Meet,” Women’s Health Activist Newsletter (September–October 2012): 6.

3. nnewh was a Toronto-based research institute that addressed the intersections of environments, paid work, chemical exposures, and women’s health. Prior to its work with nail technicians, nnewh conducted research on automotive workers’ heightened risk of breast cancer.

4. Anne Rochon Ford, “Healthy Nail Salon Network (Toronto): Building a Coalition for Change,” Women & Environments International Magazine, no. 96/97 (Summer/Fall 2016): 39–40.

5. Linor David, Focus Group Results: How Training and Employment Conditions Impact on Toronto Nail Technicians’ Ability to Protect Themselves at Work (Toronto: Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre, 2014), 7–8.

6. David, Focus Group Results.

7. Cate Ahrens, Victoria Arrandale, Anne Rochon Ford, and Lyba Spring, Occupational Health and Safety in Nail Salons (Toronto: Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre, 2018).

8. The author has been a member of the Healthy Nail Salon Coalition since 2017.

9. Healthy Nail Salon Coalition, internal planning document, 2016.

10. Margaret M. Keith, Beverley Cann, James T. Brophy, Deborah Hellyer, Margaret Day, Shirley Egan, Kathy Mayville, and Andrew Watterson, “Identifying and Prioritizing Gaming Workers’ Health and Safety Concerns Using Mapping for Data Collection,” American Journal of Industrial Medicine 39 (2001): 42–51; Dorothy Wigmore, “Body Mapping” and “Workplace Mapping,” Wigmorising (website), accessed 8 July 2022, https://www.wigmorising.ca/.

11. Margaret M. Keith, “Analysis of a Worker-Based Participatory Action Research Approach to the Identification of Selected Occupational Health and Safety Problems in Canada using Mapping,” PhD thesis, University of Stirling, 2004, 162.

12. Vanessa Agard-Jones, “Bodies in the System,” Small Axe 42 (2013): 182–192; Agard-Jones, interview by Dominic Boye and Cymene Howe, 29 September 2016, in episode 35 of Cultures of Energy, podcast, 1:08:38, accessed 8 July 2022, https://cenhs.libsyn.com/ep-35-vanessa-agard-jones.

13. Importantly, in mapping hazards and their health implications, the intention is not to represent nail technicians as passive recipients of harm. Although not the prime focus of the present work, nail technicians challenge and resist their conditions in various ways. Indeed, the very existence and proliferation of nail salons – often owned by racialized persons – is itself an example of tenacity amid labour market exclusion.

14. City of Toronto, BodySafe, accessed 8 July, 2022, https://www.toronto.ca/community-people/health-wellness-care/health-programs-advice/bodysafe/.

15. Sadaf Sanaat, D. Linn Holness, and Victoria H. Arrandale, “Health and Safety in Nail Salons: A Cross-Sectional Survey,” Annals of Work Exposures and Health 65 (2021): 225–229.

16. Leah F. Vosko, Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006), 3.

17. Ontario Ministry of Labour, Blitz Results: Vulnerable Workers (Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Labour, 2014).

18. Parkdale Queen West chc, Atkinson Focus Group (Toronto: Parkdale Queen West chc, 2019); Sara Mojtehedzadeh, “Why the Pandemic Is a Triple Whammy for Nail Salon Workers – and an Opportunity for Change,” Toronto Star, 17 July 2020, https://www.thestar.com/business/2020/07/17/why-the-pandemic-is-a-triple-whammy-for-nail-salon-workers-and-an-opportunity-for-change.html; Mojtehedzadeh, “Nail Salon Network Seeks to Empower Newcomer Women on the Job,” Toronto Star, 15 July 2018, https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2018/07/15/nail-salon-network-seeks-to-empower-newcomer-women-on-the-job.html.

19. Parkdale Queen West chc, Better Health and Working Conditions in Nail Salons – Creating Standards Together (Toronto: Parkdale Queen West chc, 2022); Parkdale Queen West chc, Atkinson Focus Group.

20. Anne Rochon Ford, “Nail Salons, Toxics, and Health: Organizing for a Better Work Environment,” in Eric Mykhalovskiy, Jacqueline Choiniere, Pat Armstrong, and Hugh Armstrong, eds., Health Matters: Evidence, Critical Social Science, and Health Care in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020), 247–262.

21. Sara Mojtehedzadeh, “Nail Salon Network.”

22. Tania Das Gupta, Racism and Paid Work (Toronto: Garamond, 1996); Winnie Ng, Aparna Sundar, Jennifer Poole, Bhutila Karpoche, Idil Abdillahi, Sedef Arat-Koc, Akua Benjamin, and Grace-Edward Galabuzi, “Working So Hard and Still So Poor!”: A Public Health Crisis in the Making; The Health Impacts of Precarious Work on Racialized Refugee and Immigrant Women (Toronto: Ryerson University, 2016); Andrea M. Noack and Leah F. Vosko, Precarious Jobs in Ontario: Mapping Dimensions of Labour Market Insecurity by Workers’ Social Location and Context (Toronto: Law Commission of Ontario, 2011); Stephanie Premji and Yogendra Shakya, “Pathways between Under/Unemployment and Health among Racialized Immigrant Women in Toronto,” Ethnicity & Health 22 (2017): 17–35; Stephanie Premji, Yogendra Shakya, Megan Spasevski, Jessica Merolli, Sehr Athar, and the Immigrant Women & Precarious Employment Core Research Group, “Precarious Work Experiences of Racialized Immigrant Women in Toronto: A Community-Based Study,” Just Labour: A Canadian Journal of Work and Society 22 (2018): 122–143; Basak Yanar, Agnieszka Kosny, and Peter M. Smith, “Occupational Health and Safety Vulnerability of Recent Immigrants and Refugees,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (2018): 2004.

23. Stephanie Premji, “‘It’s Totally Destroyed Our Life’: Exploring the Pathways and Mechanisms between Precarious Employment and Health and Well-Being among Immigrant Men and Women in Toronto,” International Journal of Health Services 48 (2018): 106–127; Premji and Shakya, “Pathways between Under/Unemployment and Health”; Stephanie Premji, Patrice Duguay, Karen Messing, and Katherine Lippel, “Are Immigrants, Ethnic and Linguistic Minorities Over-represented in Jobs with a High Level of Compensated Risk? Results from a Montréal, Canada Study using Census and Workers’ Compensation Data,” American Journal of Industrial Medicine 53 (2010): 875–885; Yanar, Kosny, and Smith, “Occupational Health and Safety Vulnerability.”

24. Ng et al., “Working So Hard,” 3.

25. A. Morgan Lay, Ron Saunders, Marni Lifshen, Curtis Breslin, Anthony LaMontagne, Emile Tompa, and Peter M. Smith, “Individual, Occupational, and Workplace Correlates of Occupational Health and Safety Vulnerability in a Sample of Canadian Workers,” American Journal of Industrial Medicine 59 (2016): 119–128; A. Morgan Lay, Agnieszka Kosny, Anjana Aery, Karl Flecker, and Peter M. Smith, “The Occupational Health and Safety Vulnerability of Recent Immigrants Accessing Settlement Services,” Canadian Journal of Public Health 109 (2018): 303–311; Yanar, Kosny, and Smith, “Occupational Health and Safety Vulnerability.”

26. Julia R. Varshavsky, Rachel Morello-Frosch, Suhash Harwani, Martin Snider, Syrago-Styliani E. Petropoulou, June-Soo Park, Myrto Petreas, et al., “A Pilot Biomonitoring Study of Cumulative Phthalates Exposure among Vietnamese American Nail Salon Workers,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (2020): 325.

27. Lexuan Zhong, Stuart Batterman, and Chad W. Milando, “voc Sources and Exposures in Nail Salons: A Pilot Study in Michigan, USA,” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 92 (2019): 141–153.

28. Aaron Lamplugh, Megan Harries, Feng Xiang, Janice Trinh, Arsineh Hecobian, and Lupita D. Montoya, “Occupational Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds and Health Risks in Colorado Nail Salons,” Environmental Pollution 246 (2019): 518–526.

29. Linh V. Nguyen, Miriam L. Diamond, Sheila Kalenge, Tracy L. Kirkham, D. Linn Holness, and Victoria H. Arrandale, “Occupational Exposure of Canadian Nail Salon Workers to Plasticizers including Phthalates and Organophosphate Esters,” Environmental Science & Technology 56 (2022): 3193–3203.

30. G. L. LoSasso, L. J. Rapport, and B. N. Axelrod, “Neuropsychological Symptoms associated with Low-Level Exposure to Solvents and (Meth)Acrylates among Nail Technicians,” Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology 14 (2001): 183–189.

31. On skin irritations: Samuel DeKoven, Joel DeKoven, and D. Linn Holness, “(Meth)Acrylate Occupational Contact Dermatitis in Nail Salon Workers: A Case Series,” Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 21 (2017): 340–344. On respiratory problems: Grace X. Ma, Zhengyu Wei, Rosy Husni, Phuong Do, Kathy Zhou, Joanne Rhee, Yin Tan, Khursheed Navder, and Ming-Chin Yeh, “Characterizing Occupational Health Risks and Chemical Exposures among Asian Nail Salon Workers on the East Coast of the United States,” Journal of Community Health 44 (2019): 1168–1179. On eye sensitivities: Thu Quach, Robert Gunier, Alisha Tran, Julie Von Behren, Phuong-An Doan-Billings, Kim-Dung Nguyen, Linda Okahara, et al., “Characterizing Workplace Exposures in Vietnamese Women Working in California Nail Salons,” American Journal of Public Health 101 (2011): S271–S276.

32. Thu Quach, Julie Von Behren, Debbie Goldberg, Michael Layefsky, and Peggy Reynolds, “Adverse Birth Outcomes and Maternal Complications in Licensed Cosmetologists and Manicurists in California,” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 88 (2015): 823–833; Miriam R. Siegel, Carissa M. Rocheleau, Kendra Broadwater, Albeliz Santiago-Colón, Candice Y. Johnson, Michele L. Herdt, I-Chen Chen, and Christina C. Lawson, “Maternal Occupation as a Nail Technician or Hairdresser during Pregnancy and Birth Defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997–2011,” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 79 (2022): 17–23.

33. Lamplugh et al., “Occupational Exposure”; Thu Quach, Kim-Dung Nguyen, Phuong-An Doan-Billings, Linda Okahara, Cathyn Fan, and Peggy Reynolds, “A Preliminary Survey of Vietnamese Nail Salon Workers in Alameda County,” California. Journal of Community Health 33 (2008): 336–343.

34. Ontario Ministry of Labour, Underground Economy – Nail Salons Phase 1 Results (Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Labour, 2018).

35. Ford, “Nail Salons, Toxics, and Health,” 253.

36. European Chemicals Agency (echa), Cosmetic Products Regulation, Annex II – Prohibited Substances (Helsinki: echa, 2022); echa, Dibutyl Phthalate Substance Infocard (Helsinki: echa, 2021).

37. Victor M. Alaves, Darrah K. Sleeth, Matthew S. These, and Rodney R. Larson, “Characterization of Indoor Air Contaminants in a Randomly Selected Set of Commercial Nail Salons in Salt Lake County, Utah, USA,” International Journal of Environmental Health Research 23 (2013): 419–433; Zhong et al., “voc Sources and Exposures.”

38. Agard-Jones, interview.

39. Agard-Jones, “Bodies in the System,” 192.

40. Agard-Jones, “Bodies in the System,” 192; Agard-Jones, interview; M. Murphy, “Alterlife and Decolonial Chemical Relations,” Cultural Anthropology 32 (2017): 494–503.

41. Murphy, “Alterlife”; M. Murphy, “Chemical Regimes of Living,” Environmental History 13 (2008): 695–703; Nicholas Shapiro, “Persistent Ephemeral Pollutants,” in Marie-Pier Boucher, Stefan Helmreich, Leila W Kinney, Skylar Tibbits, Rebecca Uchill, and Evan Ziporyn, eds., Being Material (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019).

42. Margaret M. Keith and James T. Brophy, “Participatory Mapping of Occupational Hazards and Disease among Asbestos-Exposed Workers from a Foundry and Insulation Complex in Canada,” International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 10 (2004): 147.

43. Keith, “Worker-Based Participatory Action Research.”

44. Keith, “Worker-Based Participatory Action Research.”

45. Keith et al., “Identifying and Prioritizing.”

46. Keith and Brophy, “Participatory Mapping.”

47. James T. Brophy, Margaret M. Keith, and Michael Hurley, “Breaking Point: Violence against Long-Term Care Staff,” New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy (2019): 10–35.

48. Keith and Brophy, “Participatory Mapping.”

49. Keith, “Worker-Based Participatory Action Research.”

50. For further discussion, see Reena Shadaan, “‘I Know My Own Body … They Lied’: Race, Knowledge, and Environmental Sexism in Institute, WV and Old Bhopal, India,” in Ana Isla, ed., Climate Chaos: Ecofeminism and the Land Question (Toronto: Inanna Press, 2019), 242–260.

51. Liza Grandia, “Toxic Gaslighting: On the Ins and Outs of Pollution,” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 6 (2020): 486–513.

52. Karen Messing, Bent out of Shape: Shame, Solidarity, and Women’s Bodies at Work (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2018); Messing, One-Eyed Science: Occupational Health and Women Workers (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998); Karen Messing and Katherine Lippel, “The Invisible That Hurts: A Partnership for the Right to Health of Women Workers,” Work, Gender and Societies 29 (2013): 31–48.

53. M. Murphy, Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty: Environmental Politics, Technoscience, and Women Workers (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006).

54. Renee Pualani Louis, Jay T. Johnson, and Albertus Hadi Pramono, “Introduction: Indigenous Cartographies and Counter-Mapping,” Cartographica 47 (2012): 77–79; Nancy Lee Peluso, “Whose Woods Are These? Counter-Mapping Forest Territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia,” Antipode 27 (1995): 383–406.

55. Andrew Watterson, “Whither Lay Epidemiology in UK Public Health Policy and Practice? Some Reflections on Occupational and Environmental Health Opportunities,” Journal of Public Health 16 (1994): 270–274; Phil Brown, “Popular Epidemiology and Toxic Waste Contamination: Lay and Professional Ways of Knowing,” Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 33 (1992): 267–281.

56. Phil Brown and Edwin J. Mikkelsen, No Safe Place: Toxic Waste, Leukemia, and Community Action (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 127.

57. aids and Society Research Unit Centre for Social Science Research, Mapping Workshop Manual (Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2007); Jonathan Morgan and Bambanani Women’s Group, Long Life: Positive hiv Stories (Cape Town: Double Storey Books, 2003); Jane Solomon, Living with “X”: A Body Mapping Journey in the Time of hiv and aids; Facilitator’s Guide (Johannesburg: Regional Psychosocial Support Initiative, 2002).

58. Denise Gastaldo, Lilian Magalhães, Christine Carrasco, and Charity Davy, Body-Map Storytelling as Research: Methodological Considerations for Telling the Stories of Undocumented Workers through Body Mapping (Toronto: Centre for Support & Social Integration Brazil-Canada and Centre for Spanish Speaking Peoples, 2012).

59. Ruth Marie Wilson, Patricia Landolt, Yogendra B. Shakya, Grace-Edward Galabuzi, Z. Zahoorunissa, Darren Pham, Felix Cabrera, et al., Working Rough, Living Poor: Employment and Income Insecurities Faced by Racialized Groups in the Black Creek Area and Their Impacts on Health (Toronto: Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services, 2011).

60. Lucy Lu and Felicia Yuen, “Journey Women: Art Therapy in a Decolonizing Framework of Practice,” The Arts in Psychotherapy 39 (2012): 192–200; Candice Lys, Dionne Gesink, Carol Strike, and June Larkin, “Body Mapping as a Youth Sexual Health Intervention and Data Collection Tool,” Qualitative Health Research 28 (2018): 1185–1198; Edward G. Hughes and Alicia Mann da Silva, “A Pilot Study Assessing Art Therapy as a Mental Health Intervention for Subfertile Women,” Human Reproduction 26 (2011): 611–615.

61. Ford, “Nail Salons, Toxics, and Health.”

62. As the workshops occurred prior to the covid-19 pandemic, participants did not include harms and hazards specific to covid-19.

63. An additional body map created by nail technician participants during Workshop 1 and an additional hazard map created in Workshop 2 were published in Reena Shadaan, “Healthier Nail Salons: From Feminized to Collective Responsibilities of Care,” Environmental Justice 16 (2023): 62–71.

64. Sanaat, Holness, and Arrandale, “Health and Safety.”

65. Karen Messing, “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Making Occupational Health Compatible with Gender Equality,” in Stephanie Premji, ed., Sick and Tired: Health and Safety Inequalities (Halifax: Fernwood, 2018), 103–115.

66. Messing, Bent out of Shape; Leah F. Vosko, Temporary Work: The Gendered Rise of a Precarious Employment Relationship (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000).

67. Iffath U. B. Syed and Farah Ahmad, “A Scoping Literature Review of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among South Asian Immigrant Women in Canada,” Journal of Global Health 6 (2016): 28–34.

68. Parkdale Queen West chc, Atkinson Focus Group.

69. Premji, “Totally Destroyed.”

70. Mark Stein, “Toxicity and the Unconscious Experience of the Body at the Employee-Customer Interface,” Organization Studies 28 (2007): 1229, 1230, 1233.

71. Stein, “Toxicity.”

72. Miliann Kang, The Managed Hand: Race, Gender, and the Body in Beauty Service Work (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 20.

73. Arlie Russell Hochschild, The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983).

74. Kang, Managed Hand.

75. Ng et al., “Working So Hard,” 17.

76. See, for example, Michal Adir, Catherine M. H. Combelles, Abdallah Mansur, Libby Ophir, Ariel Hourvitz, Raoul Orvieto, Jehoshua Dor, and Ronit Machtinger, “Dibutyl Phthalate Impairs Steroidogenesis and a Subset of LH-Dependent Genes in Cultured Human Mural Granulosa Cell in vitro,” Reproductive Toxicology 69 (2017): 13–18; Thomas P. Ahern, Anne Broe, Timothy L. Lash, Deirdre P. Cronin-Fenton, Sinna Pilgaard Ulrichsen, Peer M. Christiansen, Bernard F. Cole, et al., “Phthalate Exposure and Breast Cancer Incidence: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 37 (2019): 1800; Laura E. Beane Freeman, Aaron Blair, Jay H. Lubin, Patricia A. Stewart, Richard B. Hayes, Robert N. Hoover, and Michael Hauptmann, “Mortality from Lymphohematopoietic Malignancies among Workers in Formaldehyde Industries: The National Cancer Institute Cohort,” jnci: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 101 (2009): 751–761; Hai-Xu Wang, Dang-Xia Zhou, Lie-Rui Zheng, Jing Zhang, Yong-Wei Huo, Hong Tian, Shui-Ping Han, Jian Zhang, and Wen-Bao Zhao, “Effects of Paternal Occupation Exposure to Formaldehyde on Reproductive Outcomes,” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 54 (2012): 518–524.

77. Roxana Ng, “Immigrant Women: The Construction of a Labour Market Category,” Canadian Journal of Women and the Law 4 (1990): 107.

78. Grace-Edward Galabuzi, Canada’s Economic Apartheid: The Social Exclusion of Racialized Groups in the New Century (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 2006), 127.

79. Galabuzi, Canada’s Economic Apartheid; Ng, “Immigrant Women.”

80. Ng et al., “Working So Hard,” 1–46.

81. Elyane Palmer and Joan Eveline, “Sustaining Low Pay in Aged Care Work,” Gender, Work & Organization 19 (2012): 254–275; Stephanie Premji, “Immigrant Men’s and Women’s Occupational Health: Questioning the Myths,” in Premji, ed., Sick and Tired, 118–128.

82. Kang, Managed Hand.

83. Kimberly Pham, “The Vietnamese-American Nail Industry: 40 Years of Legacy,” Nails, 29 December 2015, https://www.nailsmag.com/381867/the-vietnamese-american-nail-industry-40-years-of-legacy.

84. Susan Eckstein and Thanh-Nghi Nguyen, “The Making and Transnationalization of an Ethnic Niche: Vietnamese Manicurists,” International Migration Review 45 (2011): 651.

85. Kang, Managed Hand, 140.

86. Kang, Managed Hand, 140.

87. Das Gupta, Racism and Paid Work, 28.

88. Richard Lewontin and Richard Levins, Biology under the Influence: Dialectical Essays on the Coevolution of Nature and Society (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2007).

89. Joan Benach, Juan Manuel Pericàs, Eliana Martínez-Herrera, and Mireia Bolíbar, “Public Health and Inequities under Capitalism: Systemic Effects and Human Rights” in Jordi Vallverdú, Angel Puyol, and Anna Estany, eds., Philosophical and Methodological Debates in Public Health (Springer, 2019), 163–179.

90. Linda Nash, Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and Knowledge (Oakland: University of California Press, 2006); Premji, “Immigrant Men’s and Women’s Occupational Health.”

91. Kang, Managed Hand.

92. Carl Sampson, “Beauty Products ceo Goes on Racist Rant over Vietnamese Nail Salons, Mocks Vietnamese Language,” NextShark, 7 May 2020, https://nextshark.com/vietnamese-salons-ceo-calls-enemy.

93. Edward Hon-Sing Wong, “When a Disease Is Racialized,” Briarpatch, 3 February 2020, https://briarpatchmagazine.com/articles/view/when-a-disease-is-racialized-coronavirus-anti-chinese-racism; Kang, Managed Hand.

94. Iyko Day, Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016); Manu Karuka, Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019).

95. Chinese Canadian National Council, A Year of Racist Attacks: Anti-Asian Racism across Canada One Year into the Covid-19 Pandemic (Toronto: Chinese Canadian National Council, 2020), www.covidracism.ca.

96. Kang, Managed Hand, 202.

97. Cary Wu, Yue Qian, and Rima Wilkes, “Anti-Asian Discrimination and the Asian-White Mental Health Gap during covid-19,” Ethnic and Racial Studies (2020): 1–17.

98. Keith, “Worker-Based Participatory Action Research.”

99. Jackie Liang, interview by Reena Shadaan, 15 July 2020. Liang is a nail technician and leading figure in the Nail Technicians’ Network. In recognition of her dedication and labour, Liang received the Chinese Canadian Achievement Worker’s Award (2018), awarded by the Chinese Canadian National Council.

100. Marco Armiero and Massimo De Angelis, “Anthropocene: Victims, Narrators, and Revolutionaries,” South Atlantic Quarterly 116 (2017): 352.

101. Parkdale Queen West chc, Atkinson Focus Group.

102. Jim Stanford and Daniel Poon, Speaking Up, Being Heard, Making Change: The Theory and Practice of Worker Voice in Canada Today (Vancouver: Centre for Future Work, 2021).

How to cite:

Reena Shadaan, “Multiscalar Toxicities: Counter-Mapping Worker’s Health in the Nail Salon,” Labour/Le Travail 93 (Spring 2024): 195–222, https://doi.org/10.52975/llt.2024v93.010.

Copyright © 2024 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2024.