Labour / Le Travail

Issue 93 (2024)

Note and Document / Note et document

Making Space for Creativity: Cultural Initiatives of Sudbury’s Mine-Mill Local 598 in the Postwar Era

Keywords: working-class culture, social unionism, Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, Nelson Thibault, miners, Sudbury

Mots clefs : culture ouvrière, syndicalisme social, Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, Nelson Thibault, mineurs, Sudbury

Nelson Thibault, one of the postwar presidents of Sudbury’s Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (mmsw) Local 598, played a significant role in pushing the union to provide members with a wide range of cultural activities. He knew first-hand the dehumanizing and demoralizing capacity of capitalism. He had been one of the many young men from the Canadian prairies who had criss-crossed the country on boxcars during the Depression in search of work, occasionally spending time in relief camps where a day of physical labour yielded a bed and three scant meals.

In 1939, he was hired at the International Nickel Company mine in Sudbury during the wave of employment at the outset of the war that brought thousands with him to Inco’s door. Shortly after being hired, Thibault threw himself into the work of the union to achieve improvements for his fellow Inco workers. He was among those who helped achieve the union’s certification and first collective agreement in 1944.1 By the time he was the local’s president, he and other local leaders were convinced that the union could and should do more than win concessions from the employer; in particular, it could also provide an expansive program of cultural and recreational activities “to provide for the constructive use of leisure time for the members and their families and achieving conditions of life in the home and the community, which make for health and happiness.”2

Resolute in his belief that Inco workers and their families were entitled to lives enriched by sports, recreation, and the arts, Thibault began by introducing a building fund from a 50-cent increase to monthly union dues in 1948 to allow for the purchase of property for the first union hall. Members ultimately signalled their readiness for the enrichment of cultural activities by voting in favour of the construction of not just one but five union halls. Later, they endorsed other aspects of the union’s social programming including the recruitment of dance instructors from Toronto; salaries for full-time French- and English-speaking editors for their local’s newspaper, the Local 598 News; and a $20,000 purchase of 120 acres on the shores of Richard Lake, twelve miles southeast of the city, for a summer camp. Each new feature of the union’s social program, with associated expenditures, was debated on the floor of membership meetings through the union’s long-established democratic procedures.

The union’s social programming filled a marked vacuum in Sudbury. Although the city had its share of movie theatres and a radio station, the Young Men’s Christian Association (ymca), church choirs, and even a few amateur acting groups, there was a paucity of recreational facilities such as swimming pools, sports arenas, and playgrounds. This was due to the city’s limited tax base, which was constrained by turn-of-the-20th-century legislation that exempted the buildings and machinery used by the mining companies from municipal taxation. In terms of available cultural options, there was a disparity between Sudbury’s elite, who could travel to Toronto for theatre, art galleries, and entertainment, and those of lesser means, who might more typically take in a sports game or engage in a night of heavy drinking in the bars, with their segregated “Men Only” and “Ladies and Gents” entrances.3 Consequently, the evolution of union halls, dance schools, summer camps, and sports teams spearheaded by the local over the years was the crucible for alternative forms of working-class culture in the community.

Inco’s large postwar workforce of miners and smeltermen was like a little League of Nations. Speaking to one another over the roar of a jackleg drill in the mines or the open fires of the smelters was made even more difficult by Inco’s practice of pairing Ukrainians with Germans, Franco-Ontarians with Poles, and Brits with Italians for the explicit purpose of preventing workers from banding together to challenge the supervisors’ frequent and grievous abuses of power. Many of the newcomers from Europe had pro-fascist political leanings that caused rifts with others who had fought in resistance movements. Cleavages between “Red” and “White” Finns, and similar division among the Ukrainian workers, created tensions within the workforce. While community halls were sites for the expression of the rich and varied cultural legacies of Italian, Finnish, Ukrainian, and other immigrant groups, the shared access to and collective responsibility for the union’s cultural endeavours was a powerful unifying element for this ethnically diverse workforce.

The cultural programs of mmsw Local 598 have attracted some scholarly attention, although little in comparison with the scholarship on the union itself.4 Mine-Mill’s particular brand of social unionism was part of a larger pattern, sharing with other left-led unions in the early postwar years an effort to achieve broader social improvements beyond the parameters of the newly won legal framework governing industrial relations.5 Nevertheless, as the archival documents and images presented here indicate, mmsw Local 598 was exceptional in both the nature and the extent of its programming in the arts, culture, and sports for its members and their families. The materials that follow were drawn from a variety of archives, and they are contextualized with aid of oral history interviews.6 They indicate how the leaders and membership of Local 598 made space for culture, both literally and metaphorically, for the workers of Sudbury.

The Union Halls

The first of the Mine-Mill halls was completed in 1951 and officially opened the following year on property purchased by the local. The halls, eventually five in total, were hubs ablaze with banquets, bowling nights, community dinners, variety shows, and performances by such notable singers as The Travellers, Pete Seeger, and Paul Robeson. Programming ran from the local’s Boxing Club to the Saturday Morning Club entertainment for children with cartoons and movies. There were also Sunday Family Nights and the Wednesday Afternoon Club, which provided vital babysitting services for mothers with preschool-age kids.

The popularity of activities offered at the union’s first hall, on Sudbury’s Regent Street, led to the construction of other halls in subsequent years in the outlying communities of Garson, Coniston, Creighton-Lively, and Chelmsford. An additional hall in the most distant of Inco’s communities, Levack, was contemplated by the local’s executive but was dropped in anticipation of the hefty expenses at the beginning of the 1958 strike.

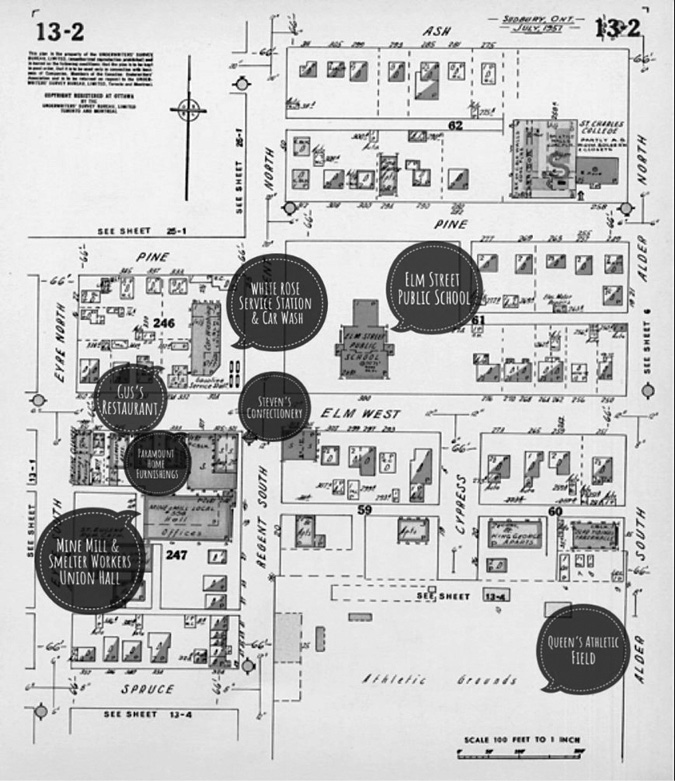

The main Mine-Mill hall, on Regent Street, was designed by the prominent Sudbury architect Louis Fabbro, who had received praise for his design of the Sudbury General Hospital and the Sudbury High School. The hall was conveniently located close to the bustling intersection of Regent and Elm Streets in the city’s rapidly expanding west-end neighbourhood. Within a few steps of the hall were businesses that miners and their families frequented.7 Notably, Gus’s Restaurant was a local institution that offered miners living in nearby boarding houses a “lunch pail service.” At the end of their shifts, men would filter in for monster meals served on large oval plates and then, on their way out, leave their empty lunch pails to be packed with sandwiches, cigarettes, and chocolate bars for pickup on the way to their next shift.

Figure 1. Regent Street Hall – Map of surrounds, 1957.

Reproduced by permission from Opta Information Intelligence, Fire Insurance Map, Sudbury 1957, sheet 13-2.

The three-storey hall at 19 Regent Street readily accommodated all types of activities. If the hall’s bowling lanes were not occupied with league practices and tournaments, they were busy with family bowling nights. Multi-purpose rooms housed choral group practices and dance classes. The fully equipped commercial-sized kitchen was a beehive of assembly-line sandwich preparation for evening meetings, bake-offs for the next bazaar, or full meal service for the steward appreciation banquets. The hall’s spacious 1,200-seat auditorium, with its sizable stage and grand piano, was regularly filled for performances by touring professional singers and dancers, as well as membership meetings. In the basement, the beverage room was a favourite destination for the miners and smeltermen coming off shift. Over a pint, they would tally up the day’s production of nickel, play a game of cribbage or shuffleboard, share the latest gossip, and debate the weight of the moose or size of fish from the weekend’s excursions.

In their third-floor offices of the hall, the secretary and elected officials carried out the work of the union: planning projects; keeping records of membership lists and financial accounts; creating and dispatching information to the members through bulletins, notices, and the local’s newspaper. The rifle tucked behind the president’s office door, hopeful for a weekend hunt, was seldom moved. There was simply too much to do to represent 14,000-plus members, and evening and weekend meetings were routine. When they could push themselves away from the Gestetner copying machine, their typewriters, and their large wooden desks piled high with papers, the staff and members of volunteer committees enjoyed a spectators’ view of the activities on the Queen’s Athletic Field across the street from their office windows. A spacious two-bedroom apartment, also on the hall’s third floor, was home to the recreation director and his family, hired to organize activities in the halls and manage the union’s various social programs.

The Regent Street hall was built in the same style as the Western Federation Miners’ 1898 hall in Rossland, BC, featuring majestic laminated arched beams. At the time of the gala opening of the main union hall in 1951, International Union vice-president Asbury Howard came to Sudbury. A Local 598 executive member remembers:

We took him on a grand tour and as Mike Solski was showing him all this beautiful stuff, Ashbury didn’t say very much. He kept looking and looking with his hands behind his back. Finally, Solski poked him, “Well, what do you think of it?” In his southern drawl Ashbury responded “Well, it sure is a beautiful building, I’ve got to say that. It’s a beautiful building. I just hope it don’t take your mind off the union.”8

At the time of his visit, Howard, an African American man, had just finished a six-month sentence on a chain gang for registering Black voters in Alabama. The facilities of the hall might have seemed, to him, luxurious diversions from the serious work of representing workers and fighting for social justice.

Summer Camp

Following the building of the Regent Street hall, Local 598 purchased property on the shores of Richard Lake, twelve miles outside of Sudbury. The summer camp opened in 1951 as a day camp with 200 boys and girls attending each week, bused from the Regent Street Union Hall in the morning and returned each night.9

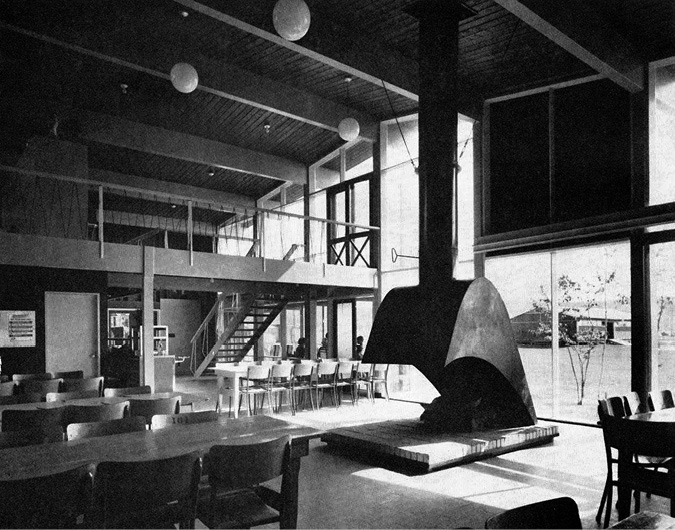

Figure 2. Mine-Mill Camp – lodge interior.

Photo reproduced from Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Journal 34, 12 (1957): 481.

In the following years, hundreds of overnight campers stayed on the 120 acres of rolling hills and quarter-mile-long beach and enjoyed a wide assortment of programs in archery, drama, hiking, baseball, softball, and social dancing. Campfire singalongs brought together all age groups. The camp’s waterfront programming included boating, canoeing, and swimming lessons, complete with Royal Life Saving Society certification managed by a full-time waterfront director and assistant director. An extensive arts and crafts program offered everything from papier mâché and weaving to leatherwork and kiln-fired clay sculpting. The twenty children in each of the four dormitories were supervised by two counsellors and two counsellors-in-training.

The camp’s majestic lodge contained the dining hall, large kitchen, library, and an open central fireplace with surrounding seating. The lodge, designed by the same architectural firm as the Regent Street hall, cost $40,000 – a considerable expense for the times. As one regular camper remembers, the library “was filled with any and all books from Winnie the Pooh to Robert Heinlein’s science fiction and reading was always encouraged.”10 With camp costs subsidized by the union, the fee of nine dollars a eek per child made the camp accessible to working-class families.11

Weir and Ruth Reid, the local’s recreational director and his wife, were beautifully matched as the camp’s co-directors. Each brought complementary, equally valuable skills and credentials to the job. Weir’s special interest in nature, theatre, and arts and crafts and Ruth’s well-honed organizational skills drew upon their extensive programming experience with the Young Women’s Christian Association (ywca). Ruth oversaw the five-member cooking staff and created the camp’s menus based on sound principles of food science that she acquired in her post-secondary education in home economics from Brescia College.12

The Richard Lake camp also welcomed the shop stewards for regularly scheduled “steward schools.” To ensure that the hard-won improvements achieved in the successive collective agreements negotiated with Inco and other employers were maintained, an educated, militant pool of shop stewards was needed. At the weekend-long training sessions, the 300-plus stewards learned the principles of unionism, details of the most recent collective agreements, and how to present a grievance.

The camp’s beach and picnic facilities were always open to the union’s members and made available to community groups for outdoor social events. On hot summer weekends, throngs of union families filled the campgrounds for afternoon picnics, swimming, and nature hikes. Young children found their way to the small zoo and playground equipment, and picnic baskets could be supplemented by the concession stand offerings. A full program designed to entertain all family members included music, games, softball tournaments, tug-of-war matches, timed competitions among miners filling mock ore cars, and wheelbarrow races with separate children and adult divisions. Shiny new silver dollars were awarded to winners as prizes.13

Given the extensive programmatic offerings, the camp’s operating expenses were significant. By 1959, the annual expenditures exceeded $25,000 – an amount far from matched by the $5,100 in income from campers’ fees, parking, and snack bar revenues.14 Each year hundreds of volunteering members made incremental improvements to the campgrounds, adding new picnic tables, planting trees, and landscaping. The camp drew workers’ children from other Mine-Mill locals as far away as Buffalo and Alabama for a rich array of creative and nature-based activities during the summer months. By the mid-1950s, the camp had attracted the attention of trade unionists throughout Canada and the United States who recognized it as a jewel of the labour movement.15

Haywood Players

Hired as recreation director in 1952, Weir Reid was given full reign to use his creative energies to establish the local’s own amateur theatre troupe. In a salute to the union’s radical lineage, the Haywood Players were named after Bill Haywood, the famous labour organizer of the Western Federation of Miners and the Industrial Workers of the World in the early 1900s. Carpenters and electricians who worked for the mining companies, Inco and Falconbridge, by day became set designers and lighting crew members in the evenings; the miners and smeltermen were the actors, stage managers, and directors. Women’s Auxiliary members and other miners’ wives sewed costumes and also found themselves under the stage lights. Casts were widely recruited with the slogan “So you want to be an actor” and assurances that no previous acting experience was required.16

Liberal allocations from the union’s budget made it possible to supply sets and costumes for the plays performed at the local’s union halls as well as provincial amateur drama festivals and competitions. Tickets, sold by shop stewards, were 50 cents in the early years and by 1958 were raised to 75 cents. Often, revenues from ticket sales were used to support the local’s dance school.

Most of the troupe’s plays were deliberately chosen to entertain while commenting on the lives of workers and the crippling effects of the Cold War on the labour movement. Among the first of the Haywood Players’ productions, in February 1954, was Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, a critique of the American dream and its role in perpetuating capitalism. Another early production was Barrie Stavis’ The Man Who Never Died, which dramatized the events that led to the arrest and execution of Joe Hill, the famous Industrial Workers of the World organizer.

The troupe’s performances of Dalton Trumbo’s The Biggest Thief in Town garnered top prizes at the annual Northern Ontario Drama Festival competition in 1956 after playing to packed houses at the union halls and earning a complimentary review in the Sudbury Star.17 This ten-character comedy in three acts portrays an undertaker seeking financial benefit from a dying industrialist. The plot was based on Trumbo’s experience as a young reporter covering the mortuary beat for the Daily Sentinel in his hometown of Grand Junction, Colorado. As Trumbo explained, “The last struggle of society to extract money from the individual occurs over the dead body. Vast establishments are incorporated for this single purpose, and millions of dollars are spent to attract customers. The go-getter gets lots of bodies and gets rich; the drudge gets few and stays poor. And the clearest way, it seemed to me, to show all of this was to take an impoverished undertaker and let him try to operate – as logically he must – under the same set of ethics that govern, say, the real estate salesman, the stockbroker or the wildcat oil driller.”18

Like Mine-Mill’s leadership, Trumbo was a frequent target of the anti-communist zealotry of the period. His career was sharply curtailed because he was blacklisted from the film industry from 1947 until 1960 for his connections to the Communist Party. He served an eleven-month jail sentence because he refused to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities.19 Mine-Mill’s choice to stage Trumbo’s play was, in all likelihood, a symbolic statement of solidarity with Trumbo and other victims of McCarthyism. That the production was so successful is indicative of significant community support for this alignment.

Other plays had less political content and were equally successful in attracting large audiences to the local’s union halls as well as gaining attention at amateur theatre festivals. The troupe’s production of Rise and Shine, by Canadian playwright Elda Cadogan, won the Best Director award at the Northern Ontario Drama Festival in 1959. The festival’s adjudicator, Mr. W. S. Milne, a well-known Toronto-based theatre producer, commended the Haywood Players for their “fresh creative” approach and affirmed that the set design, costumes, and makeup were the most original and best in the festival.20 Rise and Shine also received praise from Sudbury mayor Joe Fabbro in a letter to Mine-Mill’s recreation director.

Mine-Mill’s Haywood Players, like the Workers’ Theatre Movement (wtm) of the 1930s, harnessed the power of theatre to engender solidarity.21 Largely located in the urban centres of Toronto, Montréal, and Winnipeg, wtm plays focused on unemployment, poverty, and other perennial concerns of workers and were staged for audiences in labour temples, on picket lines, and at meetings of unemployed workers.22 The most famous of the wtm plays, Eight Men Speak, thematized the imprisonment of eight Communist Party militants in the Kingston Penitentiary in the early 1930s after they were tried and found guilty of sedition under section 98 of the Criminal Code. The Haywood Players followed in the tradition of the wtm and held the same goals of inspiring confidence in workers to seize the means of theatrical production, and to represent and see represented the issues they faced in their own lives and times.

Figure 3. Haywood Players Theatre production, 1955 – The Man Who Never Died.

Photo: F 1280 Series 10, B795, photo 6.2, Archives of Ontario. Reproduced by permission from Archives of Ontario.

Dance School

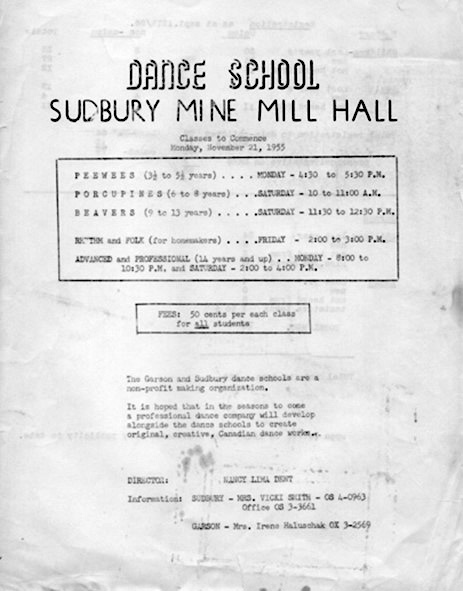

The union halls were also home to the union’s own dance school. Recruited by the recreation director, Toronto-based dancer Nancy Lima Dent established the union’s dance school in the fall of 1955. Dent brought years of both studio and stage experience. She had studied modern, ballet, and primitive dance in Toronto and New York, and for nine years she directed a Toronto modern dance company, New Dance Theatre, with ties to the United Jewish People’s Order. She performed her own choreographic works at Toronto’s Royal Alexander Theatre and Hart House, along with several stages in New York. Her repertoire consisted of dances with powerful political messages, such as “Set Your Clock at U235,” referring to uranium in atomic weapons and in concert with an accompanying Jewish folk choir, Die Naye Hagodeh (The Glory of the Warsaw Ghetto).

Dent was hand-picked for the unprecedented job of launching a dance school for miners’ children. Her varied dance background combined with her political views made her the perfect choice to undertake the task. Her connections with the United Jewish People’s Order and other left-wing groups would have brought Dent to the attention of Reid, the recreation director of Local 598, as a “fellow traveller.”23 Further, her dance pedagogy was an ideal fit for Mine-Mill’s purposes, for she considered dance as an expressive art form that could cultivate active citizenship when taught properly. By building confidence in students of dance, Dent believed they could better contribute to their communities in adulthood. In her pioneering dance pedagogy, she introduced her students to a variety of dance techniques intended to be tools for reducing divisiveness and inter-ethnic tensions. Her purpose was to empower students to express themselves with poise, imagination, and critical intelligence.

Upon her arrival in Sudbury in the fall of 1955, Dent went right to work setting up classes in the union’s halls in Garson and in Sudbury, having found, as she later recounted, “the local stages as barren as the landscape.”24 The classes began in November 1955 at 50 cents, a cost easily afforded by even the lowest-paid worker and considerably less than the fees charged by the other two dance schools in the area.25 On the advertisement for the dance classes, Dent revealed her unrestrained ambitions: “It is hoped that in the seasons to come a professional dance company will develop alongside the dance schools to create original, creative Canadian dance works” (see Figure 4).

Nancy Dent’s warm, generous spirit and infectious optimism won her the adoration of parents and children alike. In a letter to a friend, she described her reception in the communities: “We have a terrific committee of about 30 in Garson and about 80 in Sudbury. And, I have never found such a willing and cooperative group of people as here. I ask for something – it’s done. Just like that. No fuss, no bother, no ‘how do you do it?,’ no ‘well, maybe’s.’”26 Dent’s charismatic personality and cultural sophistication endeared her to a community eager for her offerings.

Figure 4. Sudbury Mine-Mill Dance School promotional flyer, 1955.

Courtesy of Dance Collection Danse, Nancy Lima Dent Collection, 101a 208.2012-1-11.

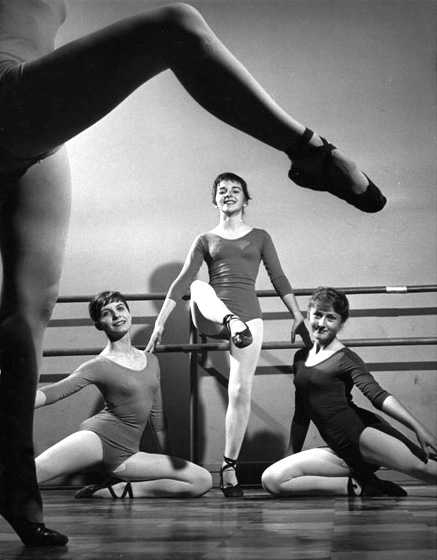

The dance classes drew adults, boys, and girls. As one male student remembers, “It was something to do and it was affordable by my parents.”27 Two or three classes ran each day, divided into age groupings that ranged from preschool to adults, named after animals: chickadees, porcupines, beavers, crows. Friday afternoon “Rhythm and Dynamics” classes attracted adults seeking novel forms of recreation. One such registrant was Betty Meakes, the entertainment writer for the Sudbury Star, who quickly became a loyal supporter of Dent and the school. Grateful for her own dance instruction, Meakes appreciated the Mine-Mill school’s contribution to the otherwise few cultural events she could cover in her newspaper column. Although these classes were open to all, most students were children of union members, and in the first year of operation, when the school attracted over 120 children and adults, only one in ten were without union affiliation.

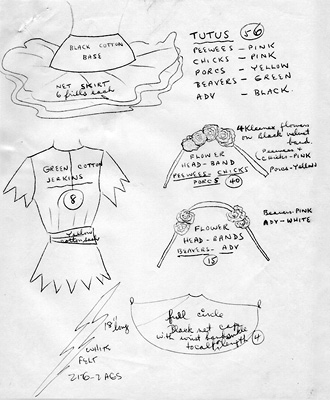

As the illustrated Dent class plan helps indicate (Figure 5), a typical dance class would start with ballet barre exercises of pliés, ronds de jamb, and developpés, mixed with leg swings drawn from modern dancer Charles Weidman. Then, the students would move into the centre of the studio for port de bras, and the “fall and recover” movement sequence taken from Doris Humphrey’s modern dance, followed by instruction on folk dances from the students’ Ukrainian, Polish, German, Russian, Italian, Finnish, and French Canadian heritages. Years later, Dent explained why she integrated folk dances into her Sudbury classes: “[In the] first place I had to translate Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, to very simple abcs because people there didn’t know who Beethoven was. Now, it was really weird, all of a sudden I was coming against people who had no idea what I was talking about, so I started again utilizing folk with them and working with the children very creatively.”28 The last half of the classes would be dedicated to composition, when students would create their own improvised dances inspired by adjectives, poems, paintings, or the textures of materials provided by Dent, such as cotton batten or silk. Her use of open-ended interpretation and other creatively inspiring approaches provided safety for students to express themselves on subjects that might otherwise be difficult.

On occasion, Dent would offer the students a storyline. Some were drawn from well-known tales such as Peter and the Wolf, and others contained traditional figures of fairy queens, princes, and princesses situated in forests full of flowers. Other possibilities deliberately broke gender norms – for example, a “good father witch” loses the many children he cares for when a “bad fairy” casts a spell, as she wrote in her class notes. The aim of the composition portion of the classes was to stimulate students’ imaginations to explore aspects of their emotions and everyday experience. By conveying what was difficult to express in words, the students’ improvisational dances could explore silent aspirations and awaken shared experiences.

Figure 5. Young People’s Classes syllabus for the Sudbury Mine-Mill Dance School under the direction of Nancy Lima Dent, c. 1956.

Courtesy of Dance Collection Danse, Nancy Lima Dent Collection, 168a 208.2012-1-12.

Figure 6. Students of the Sudbury Mine-Mill Dance School under the direction of Nancy Lima Dent, 1957.

Courtesy of Dance Collection Danse, Nancy Lima Dent Collection, 233 208.2012-1-12.

The union paid Dent handsomely. As she recalled, “The best money I ever made was in Sudbury. I was on a weekly salary with OHIP [Ontario Health Insurance Plan] payments, all sorts of conditions. I, for the first time in my life since I left home I ate, I gained about twenty pounds, I ate regular meals, oh man, wow!”29 But, it was the support from the community that she especially relished. Preparing for the first recital, in June 1956, she wrote to a friend: “Come curtain time we shall be there – for better or worse. If we pull off a half decent program for the citizens of Garson and Sudbury, it won’t be a miracle, it will be a tribute to the ability of human beings to work together to achieve worthy ambitions.”30 Community members flocked to the annual recitals held in both the Garson and Sudbury union halls.

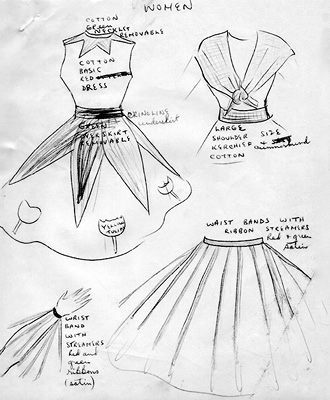

Figures 7a and 7b. Unattributed recital costume designs for the Sudbury Mine-Mill Dance School under the direction of Nancy Lima Dent, c. 1956.

Courtesy of Dance Collection Danse, Nancy Lima Dent Collection, 110 and 111, 208.2012-1-11.

The first recital in 1956, scheduled to coincide with the union’s eighth annual national convention, was an integral component of the convention’s program that also featured theatrical performances by the Haywood Players and a concert by civil rights singer Paul Robeson.

In advance of the dance recitals, a committee of fifteen women sewed costumes from Dent’s instructions and expertly drawn designs. Given the complexity and number of costumes – one recital required 56 tutus, 55 headbands, and eight men’s jackets, labelled as “jerkins” in the illustrations reproduced here (Figures 7a and 7b) – all fifteen sewers would have been busy for weeks in advance of the performances. One former student recalls dancing the role of a witch in one recital number, which endowed her with a costume she kept for many years and reused for several subsequent Halloweens.31

Recital dances heralded both traditional and contemporary subject matter, from “Cave of the Wicked Fairies” to “Peter Rabbit” and “Shopping Expedition: A Day in the Life of a Big City Department Store.” Others had political themes, with titles such as “Struggle” and “The World Will Be Ours.”

Accompanying musical selections, as eclectic as the dance technique on display, ranged from Tchaikovsky to Ukrainian, Italian, and Israeli folk songs to Aaron Copland’s score for Jerome Robbins’ 1951 production of The Pied Piper that appeared on the New York stage. Some dances were set to poems instead of music. Whether set to music or poetry, the symbolic, aesthetic vocabulary of dance was the common language for the young performers to express their varied heritages and the commonalities of their experiences as working-class children. Solidarities were built through differences, rather than in spite of differences. In one recital, a poem supplemented the overtly political solo dance that a young émigré performed. As Dent explained to the audience by way of introduction, “this dance is Tini Pel’s impression of how a people feel who have known fear and oppression, which her countrymen of Holland experienced in 1940.”32 In the years to come, Pel enjoyed a lengthy career as a dance teacher in the Royal Academy of Dance (rad) tradition. She first established the Arts Guild Ballet School in Sudbury in 1957 and later co-founded the dance division of the Junior School of the Arts in Kirkland Lake and served as artistic director of the Nickel Belt Ballet Company.

When Dent left Sudbury in the summer of 1957, the union executive was quick to find a replacement to continue the students’ cultural enrichment. Another plum recruitment, Barbara Cook, brought advanced classical ballet training and accreditation.

Surprisingly, the students readily made the transition from Dent’s expressive dance forms to the rigorous discipline of Cook’s ballet classes that adhered to the rad syllabi. The two styles of dance could not be more divergent. The sharp contrast between the two teachers, however, was in more than their dance technique. As one dance school student remembered, Cook “was so very strict in her mannerism and was not easy to get close to. As good as an instructor that she was, and she really knew her stuff, Nancy had that personality that all the parents loved her, all the kids loved her.”33

Although the students made the transition, Cook felt the need to justify her balletic focus with a lengthy proclamation on the benefits of the technique, published in a recital program:

A message to parents: Ballet exercises are scientifically planned and balanced to strengthen and shape the muscular structure of the body. Consequently, the study of ballet is beneficial to all. The exercises are one of the nicest ways to cultivate the body and the mind. … every child who studies ballet, whether for reasons of health, posture or poise, or with the desire for a professional career must be trained, to the highest professional standards, if good results are to ensure.34

Perhaps Cook’s message was a means of inserting herself into what many parents felt was a vacuum left by Dent.

Figure 8. Students of the Mine-Mill Dance School under the direction of Barbara Cook, 1959.

Courtesy of Dance Collection Danse, Barbara Cook Collection, 25 071.2009-1-9.

Cook was hired at $75 a week – a wage close to the average union member’s wage – augmented by health benefits, paid vacation, and the $15 fee for her membership in the Canadian Dance Teachers’ Association. During the thirteen-week strike against Inco in 1958, Cook was asked to accept a 50 per cent reduction in salary. In order to conserve funds, the union leaders agreed to cut their own wages in half, in a reduction from $90 to $45 a week for the duration of the strike. Along with the dance teacher, the local’s office staff and janitors in the union halls were asked to accept the same 50 per cent pay reduction. The dance school continued through the strike. As one former student remembers, “The dance school went on through thick and thin.”35

Like Dent, Cook’s students were both young and old, male and female, with union and non-union affiliations. A long-time ballet student, Debbie, whose father was a local businessman, felt no prejudice because of her non-union status. “It was an inclusive atmosphere as I remember it.”36 Cook added live piano accompanists to the school’s classes, and through her extensive connections in the dance world, she regularly arranged for weekend workshops for the students to work with high-profile choreographers brought in from Toronto. She elevated the status of the school with her Royal Academy of Dance accreditation that allowed her to hold examinations on the rad syllabi for the aspiring dancers. Under Cook’s tutelage, dance students achieved high standings through the range of rad ballet examinations. She often escorted her students to Toronto so they could challenge the advanced-level rad examinations that required examiners flown in from the international academy. Notably, one of Cook’s students was accepted into the prestigious Royal Ballet School in England after challenging the pinnacle rad examination, the Solo Seal, which requires performance in front of a full audience in a local theatre and a panel of experts.37

Another of Cook’s students, Larry, was a son of a miner working the jackleg drills 7,000 feet below the surface at Inco’s Creighton mine. Larry took the ballet classes in his Grade 10 high school year while pursuing his love of track and field athletics. His greatest ambition was to be a high jumper. Once he learned that the Russians were outstanding jumpers, he made a study of the Soviet training regime. He discovered that Valeriy Brumel, the rising high jump star soon to become the world record holder, had acquired his superior flexibility and strength by training with the Red Army Ballet Company. Larry followed suit, taking ballet classes from Cook to give him the edge in high jumping competitions. He recalls the physically challenging classes, “down on the floor and at the barre and doing things for just strengthening. I was really intrigued by just the physics of the technique. Even back then, I was really interested in the physics and the dynamics and momentum and lift.” For Larry, the stigma of being a boy taking ballet lessons was reason for secrecy with his peers. An even greater reason was the dance school’s affiliation with a union tainted by the Cold War’s red brush. “My full intent was to stay way below the radar. At that age, I didn’t want my jock friends to know that I was taking ballet. But, all hell would have broken loose at that time if my dad were to find out.” Because the Mine-Mill Dance School had the reputation of being a “commie school,” Larry didn’t tell his father of his attendance at the ballet classes. Only several decades later, in his father’s final years, did Larry reveal his patronage of the union’s dance school. His father chuckled, “Oh, yes, I would have been really, really pissed,” confirming his then-disapproval of the union’s activities.38

The dance school made a significant contribution to the cultural lives of union families. Both dance teachers, Dent and Cook, devoted the full breadth of their creative energies to developing dance in the Sudbury area. The two teachers could not have been more dissimilar in training, temperament, and area of specialization. Yet both teachers, each in her own way, were cultural benefactors to the region’s residents, their imprint felt for years to come.39 Ruminating on the impact of the dance school, former student Debbie expounded, “It saved me. It saved me because I was … Probably the other girls felt the same way. We felt very lost in a mining town. To have Barbara Cook come there and bring the gift of ballet, it was just wonderful. There were other dance schools there, but they were more acrobat, jazz, tap, whereas hers was a classical ballet. It was really lovely.”40 The school spawned the next generation of dance instructors who later established prominent schools of their own in the region as well as the Nickel Belt Ballet Company, founded by one of the school’s leading students in 1961.41

The Return of “Bread and Butter” Unionism

Mine-Mill’s innovative programming reached beyond the bargaining table to enhance the everyday lives of its members and their families in continuous and concrete ways. One of the founders of the union’s social programming summarized its origins in an interview several decades later: “We decided that we were going to have a little bit of socialism of our own. That’s really what we were saying without knowing that we were saying that.”42 Had he used the word “socialism” to describe the impetus of the union’s social program at the time, it would have fed directly into the growing, misguided perceptions that Mine-Mill was intent on spreading communist ideology, particularly among youth. Only after the buffer of intervening decades was it safe to use such a term in its broadest, most benign sense without immediately evoking Cold War paranoia.

Given the vitality of the union’s social programming, it is not surprising that it was a lightning rod for anti-communist Cold Warriors. The summer camp was cast as a training ground for Soviet spies, a site for the communist brainwashing of young minds. The reputation of the camp director as an agent of communist indoctrination was the subject of legal battles that lasted close to a decade.43

Another element of the union’s social programming that fell victim to Cold War fever involved scheduled performances in the union hall of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet (rwb). The performances were abruptly cancelled when the rwb was informed that it would have to forfeit its subsequent American tour, which included a Washington performance for President Dwight Eisenhower, if it kept its commitment to perform for the union members in Sudbury. Years later, the union leaders who had arranged the rwb performances reiterated their firm belief that the US State Department was involved in the cancellation, a conviction that has been plausibly advanced by others.44

In 1962, Mine-Mill was replaced by the United Steelworkers of America (uswa) to represent the miners and smeltermen at Inco. For three years prior, and three years following, the uswa and Mine-Mill waged war over the representation of the Inco workers. The battle for the bargaining rights of the largest union local in Canada spilled into the courts, as it did into every corner of Sudbury. Fists would fly. Men would run at each other with broken beer bottles. In the schoolyards, insults of “commie” were hurled at children of Mine-Mill stalwarts. The pubs and bars were awash with threats and shouting matches. Smashed windows, fire hoses, and illegal brass knuckles featured in several large-scale riots while police stood by with arms folded. Ties between family members would remain broken for years to come.45 The two unions, Mine-Mill and uswa, finally merged in both the United States and Canada in 1967.46

Inco workers continued their militancy for several decades. However, once organized as a uswa local, they became part of that international union’s larger, more bureaucratic and hierarchical structure. In the transition from mmsw to uswa, Inco workers sacrificed the decidedly democratic structure and procedures of a rank-and-file union. They also lost the social, recreational, and cultural programming so vital to communal well-being. By the end of the 1960s, the theatre troupe, dance school, and concerts were things of the past, and the summer camp had been greatly diminished.

In the mmsw era, the union encouraged social cohesion by bringing families together in such inclusive spaces as the badminton club, Saturday morning movie screenings, and dance school recitals, to name a few. As opportunities for members and their families to come together and share their lives, these programs fostered relationships, bridged ethnic divisions, and redistributed social power. The cultural programs sustained by mmsw were also an alternative to the “high” art found in museums, galleries, and concert halls of the elite, providing cultural forums to express the truth of working peoples’ lives and fuel their desire for equality, freedom, and, importantly, beauty. The subversive potential of such expressive fare lay in the reclamation of the means of cultural production through amusement, satire, and vision and brought balance to lives regularly dominated by the mind-blunting work of the union members.

To view a short talk by the author, as well as archival film footage of the mmsw’s cultural and social programs, visit: https://vimeo.com/quinlanprojects/minemillprograms

1. The first collective agreement, which followed shortly after certification in 1944, brought “collar-to-collar” pay, “voluntary check-off,” and an end to Inco’s tyrannical management practices. It did not win the members a wage rate increase, because of the wartime freeze on wages. Nonetheless, wages automatically improved for the miners in Local 598 because of the inclusion of “collar-to-collar” pay in the agreement. Whereas prior to the agreement, miners were paid only from the time their shovels hit the ore, “collar-to-collar” remuneration covered them from the moment they began their descent right up until they arrived back at the surface at the end of their shift.

2. John Lang, “A Lion in a Den of Daniels: A History of the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers in Sudbury, Ontario, 1942–1962,” MA thesis, University of Guelph, 1970, 170.

3. Dieter K. Buse, “Weir Reid and Mine Mill: An Alternative Union’s Cultural Endeavours,” in Mercedes Steedman, Peter Suschnigg, and Dieter K. Buse, eds., Hard Lessons: The Mine Mill Union in the Canadian Labour Movement (Toronto: Dundurn, 1995), 269–286.

4. Rick Duthie, “‘What’s That Tutti-Frutti [Dance] Stuff?’ Mine Mill’s Cold War Cultural Tool,” MA thesis, Laurentian University, 2015; Laurel Sefton MacDowell, “Paul Robeson in Canada: A Border Story,” Labour/Le Travail 51 (Spring 2003): 177–221; Ray Stevenson, “Ballet Ruse,” in Len Scher, ed., The Un-Canadians: True Stories of the Blacklist Era (Toronto: Lester, 1992), 94–95.

5. Peter McInnis, Harnessing Labour Confrontation: Shaping the Postwar Settlement in Canada, 1943–1950 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002).

6. Four Canadian archives holding mmsw and related collections were searched over a period of several years. The collections in Archives Ontario, National Archives in Ottawa, University of British of Columbia Archives, and Laurentian University Archives revealed a rich array of available empirical sources related to the union’s social and cultural programs. These included news stories, meeting minutes, press releases, negotiation transcriptions, newspaper clippings and broadcasting transcripts, union constitutions, and taped interviews conducted with union leaders, activists, and members. These sources were supplemented by the less expected trove of materials found in Canada’s foremost dance archive, Dance Collection Danse (https://www.dcd.ca).

Supplementing the archival materia0ls were oral history interviews conducted by telephone with surviving union leaders, activists, and their descendants. The semi-structured interviews followed standard oral history interview procedures, with special attention given to the recent emphasis on memory, identity, and subjectivity in oral history methodology. The consent form for interviewees, approved by the University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board, stipulated that “all identifying information will be stripped from the publications and replaced by pseudonyms.” Thus, in this article, pseudonyms are used for all the narrators in the oral history interviews I conducted under the auspices of the ethics approval. See Michael Frisch, A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990); Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson, The Oral History Reader (London: Psychology Press, 1998); Joan Sangster, “Reflections on the Politics and Praxis of Working-Class Oral Histories,” in Kristina R. Llewellyn, Alexander Freund, and Nolan Reilly, eds., The Canadian Oral History Reader (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015), 119–140.

7. These included Paramount Home Furnishings, Steven’s Confectionery Store, and the White Rose Service Station with its massive car wash.

8. Ray Stevenson, “We’re Still Here: A Panel Reviews the Past and Looks to the Future,” in Steedman, Suschnigg, and Buse, eds., Hard Lessons, 190.

9. “Union Camp Busy Spot,” Sudbury Star, 20 August 1951, City of Greater Sudbury Public Library Archive.

10. Confidential source, interview by author, 30 November 2018.

11. Local 598 paid $10,000 to cover the camp costs for the summer of 1958 so the fees could remain the same as the previous year. “Solidarity Vital as Talks Resume,” Canadian Tribune, 1 December 1958.

12. Confidential source, interview by author, 8 July 2021.

13. The History of the mmsw Local 598 (Sudbury: mmsw Local 598, 1959), filmstrip, 20:11, Ron Mann fond, Library and Archives Canada.

14. Local 598 Summer Camp Revenue and Expenditures, 31 August 1959, series I, sub-series A, file 7, p. 019, Laurentian University, Sudbury.

15. Buse, “Weir Reid and Mine Mill.”

16. “So You Want to Be An Actor,” Mine Mill News, 28 October 1955, City of Greater Sudbury Public Library Archive.

17. “Mine Mill Play Draws Full Houses for Two Nights,” Sudbury Star, 18 February 1958, Laurentian University, Sudbury.

18. Larry Ceplair and Christopher Trumbo, Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2017), 223.

19. Ceplair and Trumbo, Dalton Trumbo.

20. “Haywood Players Compete in Ontario Drama Finals,” Mine Mill News, 4 May 1959, City of Greater Sudbury Public Library Archive. Rise and Shine was later performed in every province in Canada, in 47 US states, and in England, Ireland, Australia, and South Africa.

21. As an art form experienced collectively, theatre contains all the elements of an interaction ritual and therefore cultivates solidarity. See Elizabeth Quinlan, “Staging Labour’s Renewal: An Application of the Theory of Interaction Rituals,” Canadian Review of Sociology 57, 3 (2020): 379–398.

22. Toby Ryan, Stage Left: Canadian Theatre in the Thirties; A Memoir (Downsview, ON: Canadian Theatre Review Publications, 1981).

23. Nancy Lima met Wally Dent in 1948, and they married soon after. Wally was a Communist Party member and a veteran of both the Spanish Civil War and World War II, having been badly injured in the latter.

24. Duthie, “Tutti-Frutti [Dance] Stuff,” 43.

25. The other two were the Crouse School of Dancing and the Shirley Simard school, which taught mostly acrobatics.

26. Nancy Dent to Betty Meakes, 8 May 1956, Nancy Lima Dent fond, Dance Collection Danse archive (hereafter dcd).

27. Confidential source, interview by author, 8 July 2021.

28. Nancy Dent, interview, 7 October 1983, Nancy Lima Dent fond, dcd.

29. Dent interview, 7 October 1983, dcd.

30. Dent to Meakes, 8 May 1956, dcd.

31. Confidential source, email correspondence with the author, 24 June 2021.

32. “Struggle,” poem, #208, folder 180a, 11 January 2012, Nancy Lima Dent fond, dcd. The poem uses non-gender-sensitive terms in accordance with the times; for example, “men” is used as an inclusive noun.

33. Confidential source, interview by author, 11 August 2020.

34. Recital Program, 1959, #208, folder 212a-g, 11 January 2012, Nancy Lima Dent fond, dcd.

35. Confidential source, email correspondence, 24 June 2021.

36. “Debbie” (pseudonym), interview by author, 28 October 2020.

37. The eligibility criteria to challenge the exam includes achievement of “Distinction” in the prerequisite exam, Advanced II. Thus, very few students challenge the Solo Seal exam each year in Canada. The success rate for this prestigious exam is 30 per cent, far below the corresponding rates for the other exam.

38. “Larry” (pseudonym), interview by author, 1 September 2020.

39. Julie-Anne Huggins, “Earthdancers: Dance, Community, and Environment,” MA thesis, York University, 2005.

40. Confidential source, interview by author, 28 October 2020.

41. Huggins, “Earthdancers.”

42. Nelson Thibault, interview by Mike Solski, 25 May 1981, Solski fond, file 51, tape #42, P019, Laurentian University, Sudbury.

43. Buse, “Weir Reid and Mine Mill.”

44. Stevenson, “Ballet Ruse”; Max Wyman, The Royal Winnipeg Ballet: The First Forty Years (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1978), 87; John B. Lang, review of The Raids: The Nickel Range Trilogy, Vol. 1, by Mick Lowe, Labour/Le Travail 77 (Spring 2016): 271–273; Lang, “Lion in a Den of Daniels.”

45. Confidential sources, interviews by author, 20 and 30 April 2020, 26 August 2020, 17 October 2020, 8 July 2021.

46. The Falconbridge Mine-Millers voted against the merger and became the remaining solo mmsw local until 1993, when the local merged with the Canadian Auto Workers. Significantly, following the merger with uswa, the surviving mmsw Local 598, which consisted of the Falconbridge workers, won the legal right to retain the assets of the Regent Street and Richard Lake properties purchased in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The fact that uswa did not inherit the assets is, in the words of Jim Tester, “one of labour history’s greatest ironies.” Jim Tester, interview by Rick Stow, 29 September 1994, Rick Stow fond, ISN #138004, Library and Archives Canada.

How to cite:

Elizabeth Quinlan, “Making Space for Creativity: Cultural Initiatives of Sudbury’s Mine-Mill Local 598 in the Postwar Era,” Labour/Le Travail 93 (Spring 2024): 223–245, https://doi.org/10.52975/llt.2024v93.011.

Copyright © 2024 by the Canadian Committee on Labour History. All rights reserved.

Tous droits réservés, © « le Comité canadien sur l’histoire du travail », 2024.